Entertainment

Martin Compston's Sugar-Free Diet for Line of Duty Waistcoats Revealed

Line of Duty star Martin Compston reveals his wife has put him on a strict no-sugar diet to fit into his trademark waistcoats for the upcoming seventh series of the hit BBC police drama.

Sports

Fernando Mendoza's Special Call with Tom Brady Amid Raiders Draft Speculation

Heisman winner Fernando Mendoza described his phone conversation with Tom Brady as 'special' while the Las Vegas Raiders consider drafting him first overall or trading for Lamar Jackson.

Politics

University Lecturers Struggle to Detect AI-Generated Student Work, Survey Reveals

Only 25% of university lecturers feel confident detecting AI-generated assignments, down from 42% last year, as students report using AI for nearly half their studies.

Crime

Mother and Daughters Brawl with Off-Duty Police Officers at London Cocktail Bar

A mother and her three daughters allegedly fought with five off-duty Metropolitan Police officers at a bottomless brunch in London after a comment about sexuality, court hears.

Business

Health

Weather

Australia Flood Watch and Shark Alerts After Heavy Rain

Heavy rainfall across southern Australia has put states on flood alert, with Victoria seeing double its average February rain and Sydney warning of increased bull shark activity due to murky waters.

LA Hits Record Heat After Winter Storm, NWS Issues Warnings

Los Angeles experiences unprecedented high temperatures of 91°F in late February, breaking daily records after severe winter storms caused flooding and avalanches.

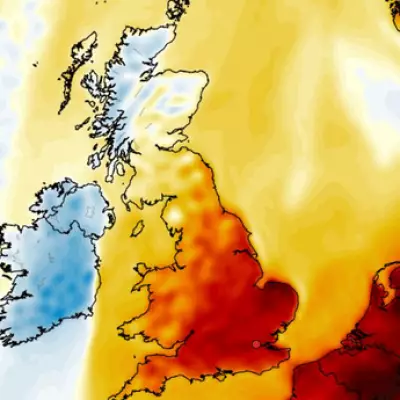

UK March Weather: Balmy Temperatures and Sunshine Forecast

The Met Office predicts above-average temperatures and high pressure for early March, with highs of 17°C in eastern England, though cooler conditions persist in the north.

Clocks Spring Forward in March 2026: Sleep Loss Looms

The clocks will go forward on March 29, 2026, marking the start of British Summer Time. This change brings lighter evenings but costs an hour of sleep, with the return to GMT set for October 25, 2026.

Security Expert Reveals How to Deter Luggage Thieves

Former US Army military policeman Ed Burnett shares crucial tips on luggage security, from color choices and tracking tech to packing strategies and danger zones, to protect your belongings while traveling.

Tech

Get Updates

Subscribe to our newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox!

We hate spammers and never send spam

Environment

UK Geography Weekend Special

Weekend special: 100 questions about UK geography. Perfect for students preparing for exams or anyone who loves learning about Britain's diverse landscapes.