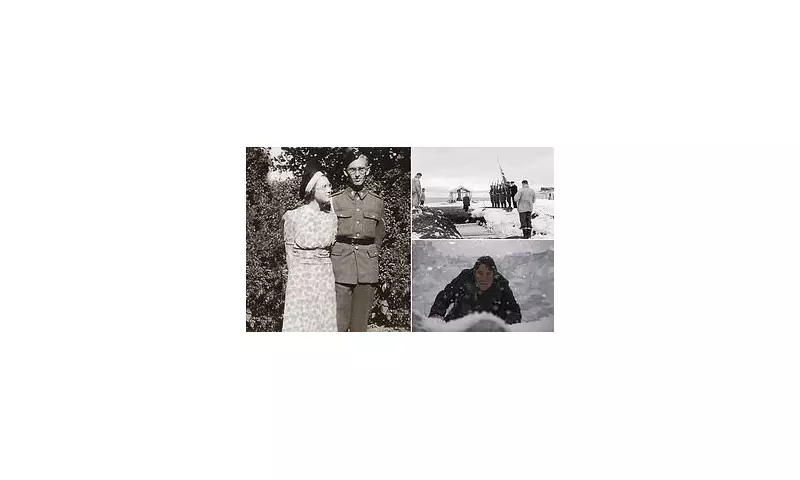

On a freezing November night in 1942, during a violent snowstorm in the Arctic, 23-year-old gunner Richard Peyer was thrown from his bunk by a sudden, violent impact. The metal hull of the steam ship SS Chulmleigh shuddered from bow to stern, and the young soldier immediately knew something was terribly wrong.

The Fateful Grounding

The 5,000-ton freighter had struck a reef just south of Spitzbergen, the largest island in Norway's Svalbard archipelago. The vessel was part of the Allied operation to supply the Soviet Union against Nazi invasion when disaster struck on November 5, 1942.

Captain Daniel Williams, aged 35, quickly assessed their dire situation. With little hope of refloating the ship or quick rescue, he made the difficult decision to order his 58-man crew to abandon ship. They faced a 150-mile journey in open lifeboats through lethally cold waters to reach the nearest settlement.

A Desperate Struggle for Survival

What followed was an extraordinary battle for survival that would last more than two months and claim the lives of all but nine crew members. The survivors endured crippling frostbite, gangrenous limbs and agonising hunger before finally making land.

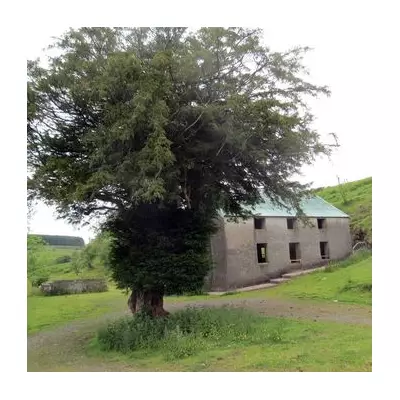

Their salvation came in the form of three small huts on a snow-covered Spitzbergen beach, though they remained 12 miles from safety. The largest hut measured just ten feet by fifteen feet, but crucially contained tins of food, a working stove, coal and matches that would prove essential for their survival.

The full horrifying story has emerged through Peyer's unpublished account, discovered by historian Hugh Sebag-Montefiore during research for his new book. The family of Peyer, who died in 2003, shared the written record of this Arctic nightmare.

Twists of Fate and Tragedy

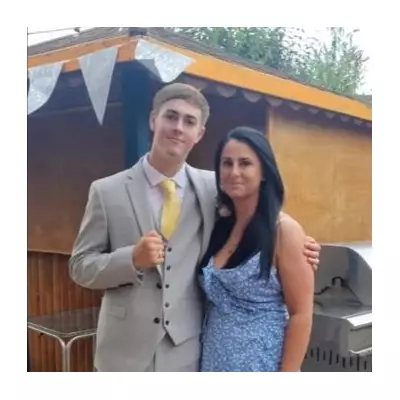

Peyer's presence aboard the Chulmleigh resulted from a remarkable twist of fate. As a sergeant based at Leith barracks in Scotland, he had been ordered to replace an ill crew member. He was only chosen because he had stayed late on September 21, 1942 to replace his boot laces.

The Chulmleigh had set sail from Iceland's Hvalfjord on October 31, 1942 as one of ten Allied ships travelling independently to Russia. This strategy emerged after previous convoys suffered massive losses to Nazi U-boats and the Luftwaffe.

After the grounding, the crew's troubles multiplied. One lifeboat overturned during evacuation, claiming their first casualty. German planes then bombed the stricken vessel. Captain Williams divided the 57 surviving crew between two larger lifeboats for the treacherous journey north.

After three days of sailing through sub-zero temperatures with boats constantly taking on water, Williams decided to use his boat's motor to speed ahead for help. The other lifeboat with 29 men was left behind and never seen again.

Descent into Madness and Desperation

As Peyer's boat pressed on, the extreme conditions took their toll. The chief steward "went mad" and died overnight. Another crew member walked overboard and had to be rescued, only to expire later. Captain Williams fell unconscious from the cold.

With the situation deteriorating, 22-year-old third mate David Clark made the critical decision to land well short of their intended destination on the night of November 11-12. Had the huts not been there, all would have perished.

The survival situation quickly deteriorated further. Some men raided the discovered food supplies, their minds affected by exposure and cold. Peyer noted that only four crew members remained fit for work. The chief engineer died, followed by several others as the cold penetrated their makeshift shelter at night.

Robert Paterson, the 25-year-old radio officer, later revealed they buried corpses under snow in rock clefts to prevent polar bears from consuming them.

Extreme Measures and Final Rescue

As starvation loomed, the younger fitter men took charge. They implemented drastic measures against those threatening the group's survival. Alfred Reid was moved to an unheated hut after developing "homicidal tendencies" and died days later. The third engineer suffered the same fate after kicking their dinner across the floor.

A crucial discovery came when gunner Reginald Whiteside found a sack of flour in another hut. This proved invaluable as rations dwindled to half an ounce of pemmican, two biscuits and two chocolate squares daily.

By December, Peyer suffered from frostbite in his knee, severe stomach pains, nosebleeds and temporary blindness. On Christmas Eve, the 16th man died since reaching land. By December 27, the flour ran out and their final rescue attempt failed.

On New Year's Day 1943, with no food remaining and gangrene spreading, salvation miraculously arrived. Norwegian soldiers on a trapping expedition discovered the nine survivors and transported them to Barentsburg on sledges.

The men wouldn't return to England until June 1943, when Royal Navy cruisers picked them up. Peyer and two comrades received the British Empire Medal, while Clark was awarded an MBE and Captain Williams an OBE.

The initial mass grave on the beach was later moved to Tromso in Norway, where gravestones still mark the tragic episode. Peyer reflected that his entire nine-month ordeal resulted from that fateful evening he stopped to replace his boot laces.