After standing derelict for more than two decades, Detroit's historic Belle Isle Zoo is finally being torn down in a major regeneration project funded by federal money.

The End of an Era

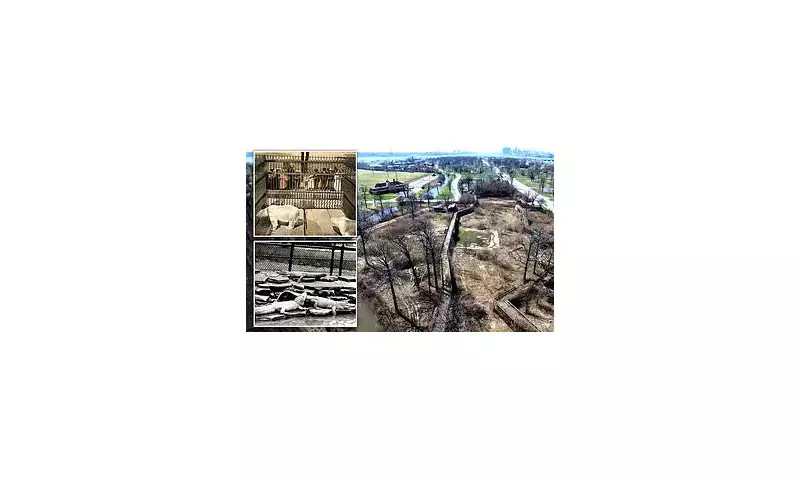

Demolition crews have moved onto the 13-acre site that has sat abandoned since the zoo's closure in 2002. For over twenty years, the former attraction has been slowly decaying behind ivy-covered fencing, becoming both a hazard and a curiosity for urban explorers.

The American Recovery Act is financing the demolition work that began earlier this month and will continue until the end of the year. Workers are focusing on removing collapsed buildings, unsafe animal cages and unstable walkways that have made the area dangerous.

Amanda Treadwell of the Michigan Department of Natural Resources explained the urgency: "A lot of the infrastructure in the old zoo is deteriorated and very dangerous. It's been hazardous for years, and we're working to remove every unsafe element."

From Humble Beginnings to City Attraction

The Belle Isle Zoo first opened its gates in 1895 with a modest collection of just a few deer and a single bear. As Detroit expanded during the early 20th century, so did the zoo, eventually becoming a major city attraction.

By 1910, officials had formally renamed it the Detroit Zoo. Over subsequent decades, the island facility housed elephants, bears, monkeys, kangaroos and numerous other species, reaching an estimated peak population of about 150 animals.

The 1920s and 1930s saw significant investment with new animal grottos, viewing pavilions and feeding stations appearing as Detroit poured resources into Belle Isle's cultural facilities.

The Schoolchildren's Elephant

One of the zoo's most cherished residents arrived in 1923 through an extraordinary community effort. When a young girl wrote to the Detroit News asking if students could pool their money to buy an animal the zoo didn't have, the newspaper launched "Elephant Day."

More than 150,000 students contributed their lunch or milk money, raising about $2,000 towards the $2,750 cost of a 600lb Asian elephant named Sheba. A reporter even travelled to New York to accompany Sheba on her journey to Detroit by train and boat.

Sheba became an instant sensation, described by reporters as "five tons of gray, ponderous beauty" and nicknamed "The Schoolchildren's Elephant." She remained a star attraction for decades until her death on January 2, 1959.

Decline and Abandonment

The Belle Isle facility began its decline after Detroit opened the larger, modern Detroit Zoo in Royal Oak in 1956. Many flagship animals relocated to the suburban campus, leaving the island site struggling with shrinking budgets and outdated enclosures.

Detroit's financial crises in the 1970s accelerated the deterioration. Buildings fell into disrepair, attendance dropped, and the zoo developed a reputation for worn exhibits. A 1980 revival attempt rebranded the facility as Safariland, complete with African-themed huts and elevated wooden boardwalks, but failed to restore long-term attendance.

By the late 1990s, funding had dried up completely, leading to the zoo's permanent closure in 2002.

Transformation Underway

Following demolition, the blighted area will be transformed with new trails, improved canal access and 110 additional parking spaces. The Michigan Department of Natural Resources is ensuring that demolition crews protect mature trees and local wildlife while removing invasive plants and unsafe structures.

During its years of abandonment, the site became a popular destination for urban explorers, graffiti artists and photographers who documented the ruins online. YouTubers regularly showcased the deteriorating elevated walkways from the 1980s redesign, noting how entire sections had sagged or collapsed beneath overgrown branches.

The abandoned zoo even found cinematic fame, featuring in the 2011 Hugh Jackman film Real Steel, where a major robot boxing scene was shot within the decaying complex.

As Glen Ryder of Harper Woods observed: "It was just sitting idle for so long, and you just had the guys coming in doing their graffiti. I think they were having a hard time even keeping people out of there all the time."

Now, after twenty years of neglect, this chapter of Detroit's history is finally being cleared to make way for new public spaces, preserving the memory while removing the danger.