My Descent Into the True Crime Machine

If you think true crime is inescapable when scrolling through Netflix or making office small talk, try working in the documentary industry. As I moved between commissioning meetings in 2015, pitching passion projects about mime history or snail behaviour, I could almost hear the inevitable question before it was asked: "Got any other ideas?" Preferably something with a body count.

This was the era when HBO's The Jinx and Netflix's Making a Murderer returned true crime to popular culture's dead centre. These shows positioned themselves as social justice projects rather than mere murder mysteries, suggesting a new beginning for the genre. Yet they soon gave way to a steady stream of interchangeable content, including Netflix's Conversations With a Killer franchise, where each season conveniently unearths long-lost interviews with notorious serial killers.

The Zodiac Killer Project That Never Was

Despite my reservations, I found myself drawn to the genre's puzzle-solving aspect. Like many viewers, I became captivated by the way clues slot together, making resolution feel tantalisingly close even in unsolved cases. My first viewing of The Staircase in 2005 convinced me of Michael Peterson's innocence, despite knowing he was actually imprisoned in North Carolina.

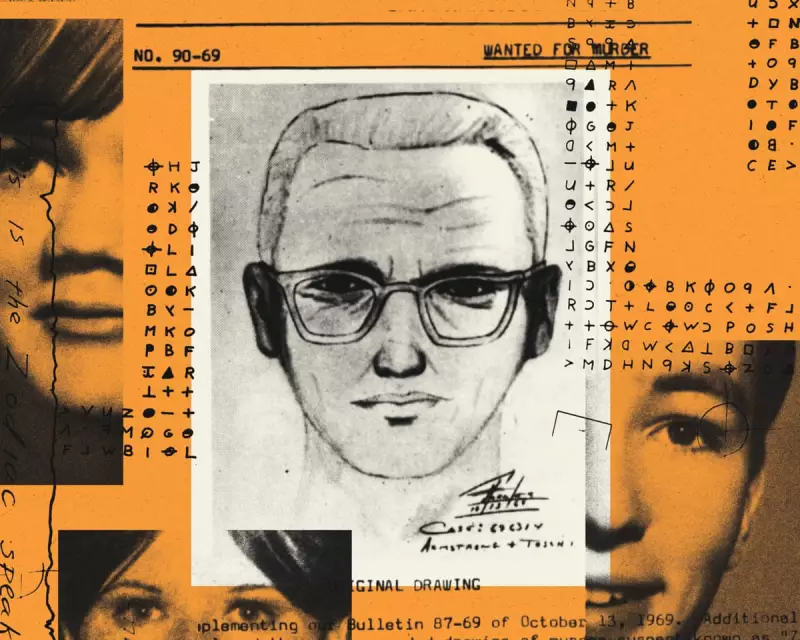

This fascination led me to Lyndon Lafferty's memoir The Zodiac Killer Cover-Up, detailing the California highway patrol officer's decades-long quest to identify the infamous Bay Area serial killer. The Zodiac Killer murdered at least five people during the late 1960s, guaranteeing his notoriety by sending enigmatic letters and cryptograms to newspapers.

Unlike Robert Graysmith's 1986 best-seller Zodiac (famously adapted by David Fincher in 2007), Lafferty's account was wonderfully idiosyncratic, filled with dramatic cliffhangers alongside classic true-crime elements: a dogged investigator, decades-old clues, and a killer still at large.

When Reality Intervenes

As I pursued adaptation rights, the film began constructing itself in my mind. I envisioned tense re-enactments of Lafferty's fateful highway rest stop encounter, sepia-toned title sequences, and interviews with ageing investigators in faded diners. I was determined to avoid the confirmation bias plaguing many Zodiac theories, presenting evidence both for and against Lafferty's suspect.

However, the mountain of contradictory evidence proved overwhelming. With half a dozen different accounts of the killer's height alone, selecting which details to include became increasingly arbitrary. This investigative excess, I realised, makes almost any crime suitable for true-crime treatment.

When I arrived in Vallejo, California – the epicentre of the Zodiac killings – in August 2022 to scout locations, reality proved far more mundane than expected. Locals seemed largely indifferent to events from half a century earlier, with my taxi driver more interested in discussing Vallejo's notable rappers than its notorious killer.

The project collapsed two days later when rights negotiations fell through unexpectedly. Without Lafferty's crusade for justice, the Zodiac case became merely a set of publicly available facts. Without his suspect looming over its inhabitants, Vallejo was just another city with a Six Flags amusement park.

Confronting True Crime's Ethical Abyss

Back in London, I found myself unable to forget Lafferty's story, describing scenes and narrative arcs of my unmade film to anyone who would listen. This frustration eventually became the subject of Zodiac Killer Project, released in cinemas on 28 November.

The finished film describes my doomed project beat by beat over footage of everyday Vallejo scenes, deliberately contrasting true crime's visual clichés with what's absent from the screen. It grapples with the genre's ethical contradictions and narrative contrivances, reflecting the ambivalence many documentary makers feel about true crime's seemingly intractable takeover.

This ethical unease permeates the industry. Even projects that affect judicial outcomes often operate within loose moral frameworks. The Jinx elicited a confession from Robert Durst but rearranged his words in post-production. Netflix's Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story justified gruesome re-enactments by claiming sympathy for victims' families, yet producers never contacted them.

As Eric Perry, relative of Dahmer victim Errol Lindsey, told the Los Angeles Times: "We're all one traumatic event away from the worst day of your life being reduced to your neighbour's favourite binge show."

The genre frequently appeals to higher authorities – justice for victims, historical importance – to justify its methods. Yet the contrast between these righteous claims and the lurid creative choices they enable creates the queasy tone defining much modern true crime.

Perhaps this explains why so many true crime productions now include sequences questioning their own appeal. Are viewers engaging in exposure therapy, wallowing in others' misery, or simply indulging voyeuristic appetites? Whatever the answer, the documentary industry positions itself as merely responding to demand.

Yet every meeting where I find myself lured back into true crime's murky waters suggests another possibility: the legions of true-crime fans are desperately trying to keep up with our supply.