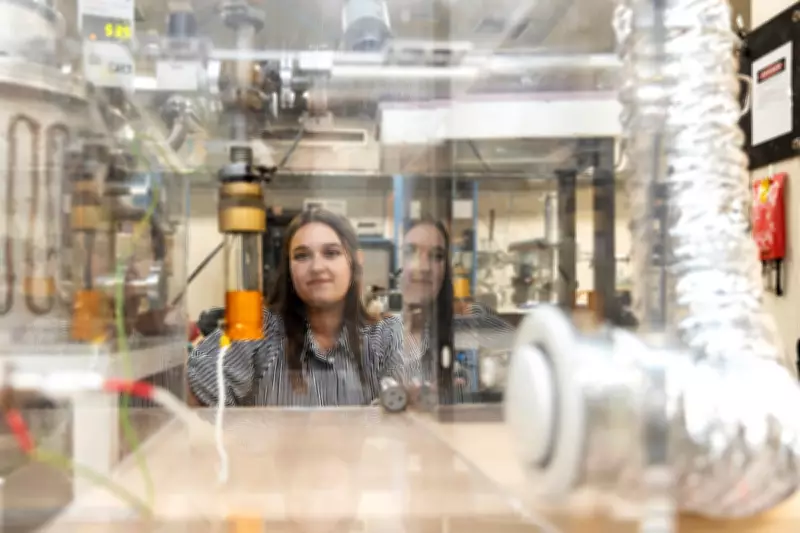

In a groundbreaking effort to unravel the mysteries of life's beginnings, a PhD student at the University of Sydney is recreating cosmic dust from scratch in a laboratory setting. Linda Losurdo, a candidate in materials and plasma physics, is reverse-engineering this celestial material to shed light on how organic compounds from space may have seeded life on our planet.

Capturing the Cosmos in a Bottle

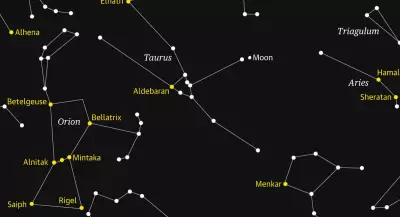

Cosmic dust, which bombards Earth in thousands of tonnes annually, originates from dying stars that expel carbon-rich waves as they reach the end of their lifecycle. While much of this dust vaporises in the atmosphere, fragments that survive as meteorites or micrometeorites offer scientists crucial insights into the cosmos. Traditionally, researchers have scoured locations like cathedral roofs in the UK to collect these microscopic specks, but Losurdo's work provides an innovative alternative by synthesising it artificially.

The Laboratory Process

Losurdo and her supervisor, Professor David McKenzie, have developed a method to simulate the conditions of space. Using a vacuum to create a near-empty environment in a glass tube, they introduce a gas mixture of nitrogen, carbon dioxide, and acetylene—mimicking the gases found around giant, dying stars. By applying a high voltage of around 10,000 volts, they energise the gas to form a plasma, producing what Losurdo describes as a "dust analogue."

This cosmic dust contains CHON molecules—carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen compounds—that are considered the chemical building blocks of life. Scientists debate whether these molecules formed on Earth, arrived via comets and asteroids, or were delivered during the solar system's early formation. Losurdo's research aims to help predict the origins of dust found in meteorite samples, using the distinctive infrared fingerprints that reveal its chemical structure.

Expert Insights and Future Applications

Dr Sara Webb, an astrophysicist at Swinburne University not involved in the study, praised the approach as "a really beautiful method" to produce material similar to interstellar dust. She noted that these dust particles were essential for life on Earth and highlighted the potential for using simulated cosmic dust in organic chemistry experiments to model early life formation on other planets.

Losurdo emphasised that her work represents a "physically plausible snapshot" rather than a universal model, aiming to compare lab-made dust with real cosmic samples. The research, published in the Astrophysical Journal of the American Astronomical Society, could pave the way for deeper understanding of how life emerged from the stars.