The remote homestead known as Lawn Hill station, situated on a riverbend south of Burketown in Queensland's far north-west, conceals one of Australia's most disturbing colonial secrets. Within its walls, forty pairs of human ears were once nailed up as macabre trophies, a chilling testament to the extreme brutality inflicted upon the local Waanyi people by white settlers during the late 1800s.

The Sadistic Pastoralists and Their Ghastly Collections

Lawn Hill was operated by two men whose names became synonymous with cruelty: Frank Hann, a pastoralist and explorer, and his station manager, Jack Watson. Historical records from contemporary newspapers describe both men as having participated in the decapitation of Aboriginal Australians, treating human remains as souvenirs or bounty. Hann, notably, maintained a group of young Aboriginal males he referred to as his 'splendid black boys', insisting they dress in white gentleman's attire while he himself cultivated a violent reputation against Indigenous communities.

Jack Watson, a daredevil from a wealthy Melbourne family, reportedly kept a collection of Indigenous men's heads, including one he used as a spittoon. The isolation of Lawn Hill—a nine-hour journey northwest from Mount Isa even today—allowed such atrocities to occur with impunity, far from the scrutiny of colonial authorities.

Emily Creaghe's Shocking Diary Discovery

The eyewitness account that brought this horror to light lay hidden for over 120 years. Emily Caroline Creaghe, the first white woman to explore outback Australia, documented her visit to Lawn Hill in 1883 within her personal diary. Her manuscript remained undiscovered on the shelves of Sydney's Mitchell Library until relatively recently, with historian Peter Monteath eventually publishing its contents.

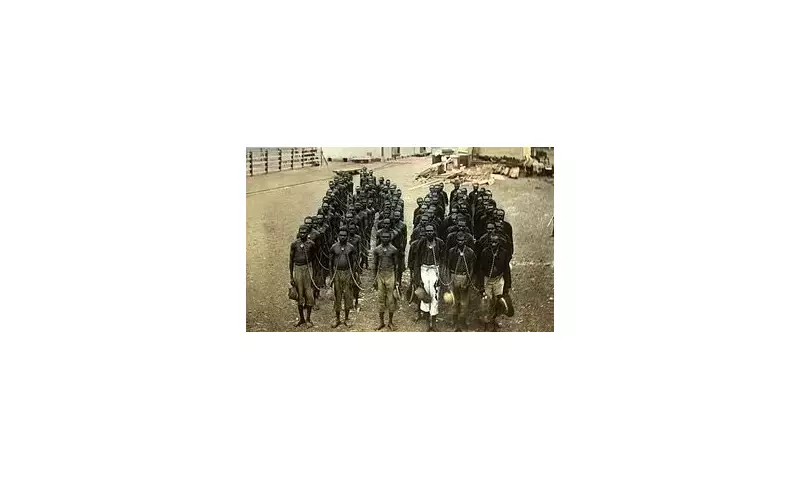

On March 8, 1883, the 22-year-old newlywed wrote: 'Mr Watson has 40 pairs of blacks' ears nailed around the walls collected during raiding parties after the loss of many cattle speared by the blacks.' Her entries, while employing racist terminology now recognised as deeply offensive, provide undeniable evidence of the property's gruesome displays. Creaghe further described disturbing scenes of Indigenous people being dragged by ropes around their necks and chained to trees until 'tamed'.

Oral Histories and Wider Frontier Violence

Creaghe's account corroborates stories passed down through Waanyi elder Alec Doomadgee, whose grandfather, stockman Stanley Doomadgee, relayed oral histories detailing Hann's brutality alongside accounts of rape, child molestation, murder, and revenge against the Waanyi people. This violence occurred within the broader context of fierce competition for resources as Europeans pushed into Aboriginal lands across northern Australia.

Historian Peter Monteath describes this period in the Gulf country and Northern Territory as 'very tense and troubled times in the northern frontier', where explorers and pioneers travelled in a state of paranoia. Additional stories describe Watson punishing an Aboriginal man by impaling his palms on a sharpened sapling and boasting about lashing people with a stock whip fitted with wire.

Systemic Brutality Beyond Lawn Hill

The atrocities at Lawn Hill were not isolated incidents but part of a widespread pattern of violence against First Nations people across colonial Australia. In Western Australia, Noongar people were forced off traditional lands, leading to starvation and conflict. Aboriginal people were arrested for theft and trespassing, then shackled with neck chains in prisons like Wyndham Gaol and Rottnest Island—a practice authorities falsely claimed was 'more humane' than handcuffs.

Between 1838 and 1931, approximately 4,000 Aboriginal men and boys were imprisoned in the Aboriginal-only Rottnest Island Prison, where hundreds died in custody. Massacres such as the Forrest River massacre in 1926, where 20 Aboriginal people were killed and their remains burned, demonstrate how such violence continued into the twentieth century with little accountability.

Queensland's Bloody History and National Reckoning

Queensland itself bears what is often described as the bloodiest history of massacres against Indigenous Australians. Before Hann and Watson's ear collection in the 1880s, colonists committed atrocities like the 1842 Kilcoy and 1847 Whiteside poisonings, where flour laced with strychnine killed about 70 Aboriginal people in each location. The 1872 massacre at Skull Hole near Winton allegedly claimed over 200 Indigenous lives.

Nationally, estimates of Aboriginal deaths from frontier conflicts range between 20,000 and 65,000, with approximately 1,500 killed in Queensland alone during the nineteenth century. These historical truths fuel ongoing debate about Australia Day, referred to as 'Invasion Day' by many Indigenous Australians, which marks the 1788 landing of the First Fleet at Sydney Cove.

The story of Lawn Hill station, preserved through Creaghe's diary and Waanyi oral history, serves as a stark reminder of the brutal realities of colonial expansion. As Australia continues to grapple with its past, such accounts underscore the importance of acknowledging frontier violence and its enduring legacy for First Nations communities.