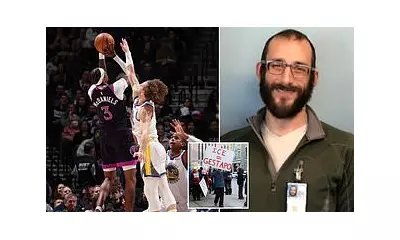

ICE's Facial Recognition App Faces Mounting Opposition in Minnesota

Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents across the United States are increasingly deploying a controversial smartphone application called Mobile Fortify, which utilises facial recognition technology to scan individuals' faces. The app allows officers to simply point a phone camera at a person and instantly retrieve data from multiple federal and state databases. This practice has ignited significant backlash from protesters, legal experts, and lawmakers who raise serious concerns about privacy violations and the technology's reliability.

Widespread Use and Legal Challenges

According to a lawsuit filed by Illinois and Chicago against the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) earlier this month, Mobile Fortify has been used to scan faces and fingerprints in the field more than 100,000 times. This represents a dramatic expansion from previous uses of facial recognition technology, which were largely confined to investigations and ports of entry. The app's existence was first revealed last summer through leaked emails obtained by 404 Media, which later reported that internal DHS documents state individuals cannot refuse to be scanned.

Nathan Freed Wessler, deputy director of the ACLU's speech, privacy and technology project, warns that "a false result from this technology can turn somebody's life totally upside down." He emphasises that ICE is operating in conditions that typically produce the highest false match rates, noting the "chilling" implications for democracy as the agency attempts to create what he describes as a "biometric checkpoint society."

Accuracy Concerns and Racial Bias

Underpinning the resistance to ICE's facial recognition programme are substantial doubts about the technology's efficacy. Research consistently shows higher error rates when identifying women and people of colour compared to scans of white faces. ICE's use often occurs in fast-moving, high-pressure situations where lighting may be poor and subjects might be turning away from officers – all factors that increase the likelihood of misidentification.

The Illinois lawsuit specifically challenges DHS's use of Mobile Fortify, arguing it exceeds congressional authorisation for biometric data collection. The complaint cites multiple instances where federal agents allegedly photographed or scanned US citizens across Illinois without obtaining consent. This follows reporting by 404 Media that the app's database contains approximately 200 million images.

Legislative Response and Public Protest

Democratic lawmakers introduced legislation on 15 January that would ban DHS from using Mobile Fortify or similar applications except for identification at official entry points. This bill follows a September letter from senators to ICE demanding more information about the app and declaring that "even when accurate, this type of on-demand surveillance threatens the privacy and free speech rights of everyone in the United States."

Protesters have employed various tactics to counter ICE's surveillance efforts, including recording masked agents, using burner phones, and installing donated dashboard cameras according to Washington Post reports. The backlash extends beyond street demonstrations to courtrooms and Capitol Hill, reflecting growing public concern about government surveillance overreach.

Technology Limitations and Policy Reversals

Jake Laperruque, deputy director of the security and surveillance project at the Center for Democracy & Technology, emphasises that "facial recognition – to the extent it should be used at all – is really supposed to be a starting point." He warns that treating it as definitive identification leads to errors and wrongful arrests, noting that even police departments nationwide typically use the technology only as an investigative lead rather than conclusive evidence.

At least fifteen states have implemented laws limiting police use of facial recognition, with San Francisco becoming the first major US city to ban the technology for all government agencies in 2019. DHS issued a directive in September 2023 requiring bias testing and opt-out provisions for citizens, but this policy appeared to be rescinded in February of last year according to available information.

Broader Implications and Ongoing Litigation

ICE's enforcement stops – whether involving facial scans or not – face continued legal challenges. These encounters are often referred to as "Kavanaugh stops" after Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh wrote that Hispanic residents' "apparent ethnicity" could be a relevant factor for ICE to stop them and demand proof of citizenship. The ACLU recently sued the Trump administration, accusing immigration authorities of racial profiling and unlawful arrests.

Observers note that ICE agents frequently fail to request consent for facial scans and may disregard other documentation that contradicts the app's data. 404 Media reported this month that Mobile Fortify misidentified a detained woman during an immigration raid, producing two different incorrect names. Despite these concerns, DHS maintains that the app "operates with a deliberately high matching threshold" and only queries limited immigration datasets, asserting it does not violate constitutional rights or compromise privacy.