Inside Helsinki's Vast Underground Bunker Network

A formidable granite wall, engineered to withstand multiple explosive blasts, stands between two heavy metal doors at the entrance to the Merihaka shelter in central Helsinki. In an emergency scenario, residents would pass through this double entryway into a sealed decontamination chamber, complete with taps and showers to wash toxic materials from clothing, before proceeding into the main bunker carved 25 metres deep into the bedrock below Finland's capital.

A Network Built for Nuclear Survival

Merihaka represents just one component of Helsinki's extensive underground shelter system—a labyrinth of winding tunnels and expansive chambers specifically designed to endure nuclear attacks and heavy shelling while accommodating hundreds of thousands of people. "We are prepared," states Nina Järvenkylä from the Helsinki Rescue Department, gesturing toward neatly stacked bunk beds and rows of dry toilets. "If there's a war, we know what to do."

During an attack, this particular bunker can hold up to 2,000 individuals, though at full capacity it becomes cramped with triple-tiered bunks. The ventilation system allows for complete sealing, while curtains can partition halls to create separate spaces for children, private areas for the elderly, or first-aid stations.

Historical Context and Modern Preparedness

Given Finland's 1,343-kilometre shared border with Russia and a turbulent history that includes losing the eastern province of Karelia during World War Two, the nation's conflict preparedness is deeply rooted. "We have had 80 years to prepare," adds Järvenkylä, noting that Helsinki's shelter system has been continuously strengthened since its establishment during the Second World War.

The 2014 occupation of Crimea and Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 underscored the reality of traditional warfare, prompting the Finnish government to adopt a comprehensive security strategy focused on protecting all citizens during military threats.

Dual-Purpose Design and Emergency Protocols

Like numerous shelters across Helsinki, Merihaka serves a dual purpose, with halls currently housing sports facilities, a café, and a children's play area. The city rents these spaces under agreements requiring clearance within 72 hours during emergencies. The emergency process is clearly defined: a city-wide siren sounds (tested monthly on the first Monday) accompanied by app alerts, advising residents to gather backpacks with food, medicine, children's toys, and personal belongings before heading to their nearest shelter.

Helsinki maintains designated shelter space for every resident—with capacity for approximately 950,000 people in a city of 700,000—accessible within one to ten minutes. Finland boasts around 5,500 civil defence shelters in Helsinki and some 50,500 nationwide, accommodating about 4.8 million people, equivalent to roughly 85 percent of the population.

The '72-Hour' Readiness Culture

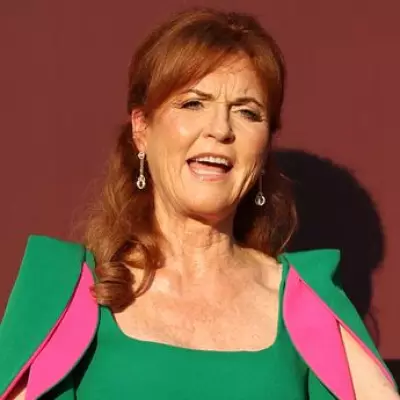

On a Thursday evening, Rebecca Harkonen, 27, plays with her two young sons in the bunker's children's area, where laughter and the sounds of a children's hockey game contrast sharply with the space's primary defensive purpose. "We all know where our closest shelter is. That's normal for us," Harkonen remarks as her four-year-old dives into a ball pit.

She references the widely recognised "72-hour concept" detailing home preparedness expectations across Finland. Residents are advised to maintain three days' worth of food, water, medicines, and essentials like battery-powered torches, iodine pills, portable stoves, matches, and fire extinguishers at all times. Harkonen stores canned food, beans, lentils, oatmeal in plastic bags, and rye bread (which stays fresh for three days) to meet these requirements.

Emergency services recently distributed leaflets at Helsinki's public library educating residents about what three days of supplies should encompass, displaying examples including bottled water, freeze-dried packets, coffee jars, and canned food. The literature emphasises knowing reliable information sources during disruptions and coping in progressively colder residences.

National Resilience Without Panic

Lt Col Annukka Ylivaara, Assistant Secretary General of the government's Security Committee, observes that Finns are neither panicking nor hysterical but remain acutely aware of the threat across their border. "In a conflict situation, Finland would be ready," she asserts. "We have kept our conscription system and our reservist army. So it's something that we are prepared for if it is needed." This combination of advanced infrastructure and cultural readiness forms Finland's robust defence posture against potential aggression from the east.