Concerning new research indicates that adhering to a high-fat, low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet could significantly elevate the risk of developing liver cancer over a period of around twenty years. The study, conducted by scientists in the United States, reveals that such diets can fundamentally alter the biology of liver cells, priming them for disease.

The Cellular Trade-Off: Survival at a Cost

US researchers discovered that repeated exposure to a high-fat diet forces liver cells, known as hepatocytes, into a more primitive state. While this adaptation helps the cells survive the stress of processing excess fat, it comes with a dangerous trade-off: a heightened vulnerability to becoming cancerous. The study was published in the prestigious journal Cell.

Professor Alex Shalek, director of the Institute for Medical Engineering and Sciences and a co-author of the research, explained the mechanism. "If cells are forced to deal with a stressor such as a high fat diet over and over again, they will do things that will help them to survive, but at the risk of increased susceptibility to tumorigenesis," he stated. Tumorigenesis is the process where normal cells mutate and become cancerous.

From Mice to Humans: A Slow-Moving Threat

The team's experiments involved feeding mice a diet very high in fat and using advanced cell-sequencing to track the liver's response. Early on, the liver cells activated genes promoting survival and growth, while simultaneously shutting down genes essential for normal liver function.

"This really looks like a trade-off, prioritising what's good for the individual cell to stay alive in a stressful environment, at the expense of what the collective tissue should be doing," said Constantine Tzouanas, a Harvard-MIT graduate and study co-author.

By the study's conclusion, nearly every mouse on the high-fat diet had developed liver cancer. The researchers found that once these adapted cells acquire a damaging mutation, they are primed to rapidly become cancerous. "Once a cell picks up the wrong mutation, then it's really off to the races and they've already got a head start on some of those hallmarks of cancer," Tzouanas added.

When the scientists analysed human patients with various stages of liver disease, they observed the same pattern: genes for cell survival thrived while those for normal liver function deteriorated. This pattern allowed them to predict patient survival outcomes. Patients with higher expression of these pro-survival genes survived for less time after tumours developed.

While most mice developed cancer within a year, the scientists stress this process is much slower in humans, unfolding over approximately two decades. However, lifestyle factors like excessive alcohol consumption and viral infections can accelerate this timeline by similarly pushing liver cells toward an immature state.

The Rising Tide of Liver Disease in the UK

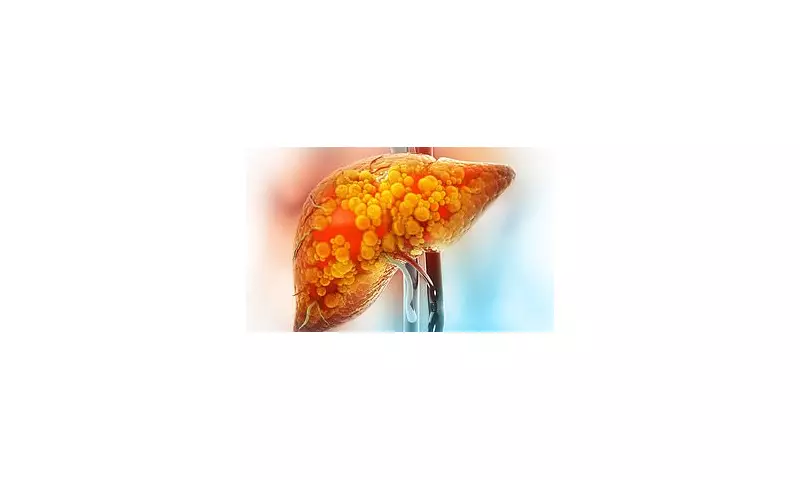

The ketogenic diet, often comprising 75% fat, 20% protein, and just 5% carbohydrates, stands in stark contrast to NHS advice, which advocates for over 50% carbohydrates, 30% fat, and 15% protein. High-fat diets have long been linked to steatotic liver disease, where excess fat builds up in the liver, causing inflammation, liver failure, and ultimately cancer.

Despite multiple studies highlighting potential dangers, the keto diet's popularity has soared, boosted by endorsements from celebrities like Gwyneth Paltrow, Jennifer Aniston, and Halle Berry. Concurrently, liver disease, once largely confined to the elderly and heavy drinkers, is rising rapidly among younger adults.

The British Liver Trust estimates that liver disease may now affect one in five people in the UK, with some experts warning the true figure could be as high as 40%. Alarmingly, around 80% of cases remain undiagnosed due to a lack of obvious symptoms. Approximately one in four patients will develop an advanced form of the disease, leading to irreversible scarring, organ failure, and cancer.

The research team now aims to investigate whether this cellular damage can be reversed through a healthier diet or with the aid of GLP-1 weight loss drugs like Mounjaro. Professor Shalek expressed hope, stating, "We now have all these new molecular targets and a better understanding of what is underlying the biology, which could give us new angles to improve outcomes for patients."