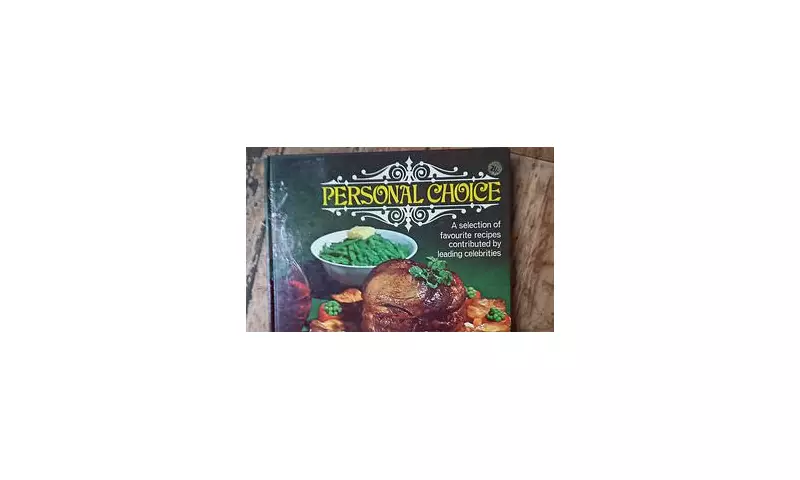

Stumbling upon a fifty-year-old cookbook in a Stornoway Co-op honesty box has revealed a fascinating window into Britain's culinary past. The discovery of Personal Choice: A Selection of Favourite Recipes Contributed by Leading Celebrities highlights just how dramatically the nation's eating habits have transformed since the 1970s.

A Glossy Relic of a Bygone Era

The cookbook, a time capsule from half a century ago, features contributions from celebrities like Dame Julie Andrews, Lulu, and Roger Moore. Yet its lurid photography and unappetising recipes immediately date it. The cover features a prawn cocktail that looks more like a prop than food, setting the tone for what's inside.

Many recipes appear over-engineered and unappealing, raising questions about whether the celebrities actually cooked them. Did Lord Longford genuinely enjoy preparing Tahitian chicken with flaked almonds and glacé fruit? It seems more likely that harried agents rifled through the wilder pages of Fanny Cradock to concoct these dishes at short notice.

The Age of Tinned Foods and Aspic

The book perfectly captures a specific moment in British culinary history. This was an era defined by cutlet frills, piped coloured mash, and foods set in aspic. Recipes relied heavily on tinned and packaged ingredients, featuring lard, dripping, food colouring, and powdered gelatine.

Yehudi Menuhin's lasagne verde called for tinned artichoke hearts, while Mary Quant's chicken soufflé depended on two cans of condensed chicken soup. These creations represented less a meal than what the author describes as a 'hostage situation' for the palate.

One notable exception was Robert Carrier, whose moules marinière, coq au vin and raspberry peach cup sounded genuinely appetising. The American food writer left an enduring legacy by popularising the casserole in British homes.

The Social Context of Britain's Culinary Decline

The fundamental flaw of Personal Choice lies in its purpose. These weren't recipes for everyday meals but for self-conscious entertainment. The elaborate presentations with avocado and grapefruit reflected the era's dinner party culture, complete with the ominous hum of the Hostess Trolley.

Britain's culinary challenges had deeper roots. The Industrial Revolution severed many people's connection to the countryside and fresh produce. The widespread collapse of domestic service after the Great War ended the era when many households relied on staff to cook.

The damage was compounded by Second World War rationing, which lasted until 1954 and did abiding damage to the national palate. This was followed by the advent of heavily processed foods and the deep freeze, creating a perfect storm for poor eating habits.

The Road to Culinary Recovery

By the 1980s, a revolution was brewing. Figures like Mary Berry, Jane Grigson, and Gary Rhodes began championing common sense in cooking. The influence of Elizabeth David, though not as commercially successful as later chefs like Jamie Oliver, gradually changed British attitudes through proponents like Terence Conran and Nigel Slater.

The new approach emphasised minimal recipes from fresh, carefully sourced ingredients and a more informal style of entertaining. The era of brunches and kitchen suppers in weekend pullovers had arrived, marking a significant departure from the formal dinner parties of the 1970s.

As Nigel Slater aptly noted in 1994 about his chicken korma, 'I am only making something for supper, you know – not entertaining a Moghul emperor.' This sentiment captures Britain's journey from culinary awkwardness to comfortable, honest cooking.