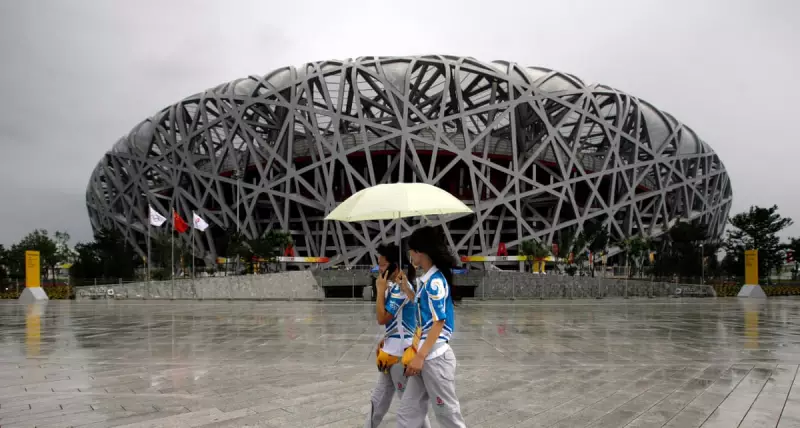

When the Taiwanese rock band Mayday prepared for a concert at Beijing's National Stadium in May 2023, fans fretted that rain might disrupt the show. Little did they know the iconic venue, known as the Bird's Nest, was engineered to welcome the downpour. The stadium's secret lies in a sophisticated network of capillary-like tubes woven through its outer steel lattice, designed not to repel water, but to capture it.

From Olympic Venues to Corporate HQs

This system channels rainfall into three substantial underwater storage tanks. Here, the water is filtered and repurposed for the stadium's needs. The Chinese ministry of water resources states this harvested rainwater meets over 50% of the building's water demands, from flushing toilets to washing the athletics track and irrigating surrounding lawns. Annually, the system can process a staggering 58,000 tonnes of rainwater.

The Bird's Nest, built for the 2008 Olympics, is a flagship example of China's push for Urban Rainwater Harvesting (URWH), but it is far from alone. Directly opposite, the National Aquatics Centre boasts its own harvesting setup, collecting roughly 10,000 tonnes of rainwater each year—equivalent to the usage of 100 households. On a city-wide scale, Beijing now reuses 50 million cubic metres of rainwater annually, with recycled sources meeting more than 30% of the capital's total water needs.

The practice extends beyond public infrastructure. In 2022, drone giant DJI unveiled its sleek new headquarters in Shenzhen, featuring sky gardens and an integrated rainwater system to irrigate its green spaces. This demonstrates how URWH has become a cornerstone of contemporary Chinese architectural design.

The 'Sponge City' Revolution

This modern movement is deeply rooted in history, revitalised through the "sponge city" concept pioneered by landscape architect Yu Kongjian. The strategy, officially adopted by the Chinese government in 2014, uses permeable surfaces, green spaces, and wetlands to absorb rainfall, mitigating flood risks in the humid south and addressing chronic water shortages in the arid north.

"China has a special affinity for rainwater," explains Wang Dong, director general at Yu's firm, Turenscape. He traces the philosophy back to traditional courtyard homes, where roofs were designed to channel precious rainwater—symbolising wealth—into the family's central space. "Chinese people have long highly valued the utilisation of water resources, it is deeply embedded in our DNA," Wang adds.

The government's ambition is now for 70% of all rainfall in designated sponge cities to be captured and reused. The economic potential is vast, with China's URWH industry, encompassing tanks and filtration systems, reportedly valued at 126 billion yuan (£13.5bn) in 2023.

Architectural Integration and Public Benefit

Implementing URWH is complex, requiring separate "grey water" piping systems to keep recycled water distinct from potable supplies. However, architects champion the challenge. Dan Sibert, a senior partner at Foster + Partners who worked on the DJI headquarters, emphasises its foundational role. Effective rainwater reuse is "absolutely fundamental to the development," he states. "It's not a sort of add-on that comes a bit later on."

For Sibert, the excitement lies in transforming a potential constraint into an asset that improves life for building users. Beyond clear environmental benefits, he notes that awareness of using grey water for tasks like toilet flushing fosters a tangible sense of occupying an ecologically responsible space. "It's good that people know that," he says.

From an ancient practice recorded as early as the Qin and Han dynasties to a modern national strategy showcased on the global stage of the Olympics, China's embrace of urban rainwater harvesting represents a profound fusion of historical wisdom and cutting-edge innovation in the face of pressing environmental challenges.