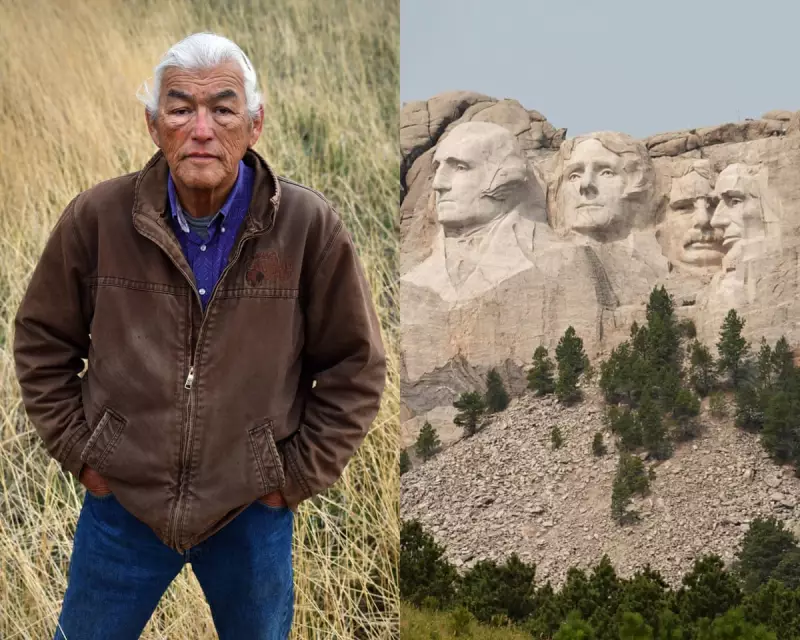

One hundred years after work began on the colossal presidential faces carved into South Dakota's Black Hills, Mount Rushmore's complex legacy is undergoing a profound reassessment. The monument, visited by nearly three million people annually, stands on land considered sacred by Native American tribes – land taken from them in violation of treaties.

The Sacred Land Beneath the Stone

The Black Hills, known as Paha Sapa to the Lakota people, represent far more than granite suitable for carving. For generations, these mountains have held deep spiritual significance as a place of worship and connection to ancestors. The 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty guaranteed this territory to the Lakota, but the discovery of gold soon led the US government to seize the land back.

A Century of Contested Memory

Since sculptor Gutzon Borglum began his work in 1925, Mount Rushmore has embodied a paradox: celebrating American ideals while standing on appropriated land. "It's a monument to freedom built on stolen land," notes historian Dr. Aaron Spry, whose research focuses on Indigenous perspectives of national monuments.

The National Park Service, which manages the site, has begun implementing significant changes to address this history:

- Expanded educational programmes highlighting Native American perspectives

- Collaboration with tribal historians on new exhibition content

- Integration of Indigenous voices into guided tours and audio materials

Towards a More Inclusive Narrative

Recent years have seen growing recognition that the full story of Mount Rushmore must include both the artistic achievement of the carving and the painful history of its location. Visitor centres now feature exhibits exploring the land's significance to Indigenous peoples, marking a significant shift from earlier interpretations that largely ignored this perspective.

As the monument enters its second century, the conversation continues to evolve. While the carved presidents gaze eternally across the landscape, the voices of those who first called this place sacred are finally being heard, creating a more complete and honest telling of American history.