Silence and Cry: Jancsó's Hypnotic 1968 Exploration of Hungarian Trauma

Miklós Jancsó's enigmatic 1968 film Silence and Cry stands as a profoundly strange and somnambulist cinematic ballet. This work implicitly juxtaposes a specific fragment of Hungary's political history with the postwar Soviet-dominated present, where nations like Czechoslovakia and Hungary faced crushing suppression. While depicting the brutality of anti-Communist forces in 1919 might have been an officially acceptable subject at the time, the film's indictment of such violence carries a clearly transferable, timeless quality. It presents an impenetrable psychological trauma infused with weird erotic overtones, akin to an absurdist nightmare transcribed by Franz Kafka himself.

A Vast, Unforgiving Landscape as Stage

The scene unfolds on the immense Hungarian plain, where a desolate wind perpetually blows. Here, characters perform their roles as if on a gigantic, open-air stage—a single, unitary space that appears to extend, Sahara-like, to the far horizon in every direction. Figures do not merely enter and exit conventionally; instead, they are often seen gradually emerging from an impossibly distant point, or departing by progressively dwindling into vanishingly small dots on the landscape. Jancsó's distinctively sinuous camerawork glides and swoops elegantly around the action in a series of mesmerising, long, unbroken takes, enhancing the film's dreamlike, balletic quality.

Post-War Paranoia and Hidden Crimes

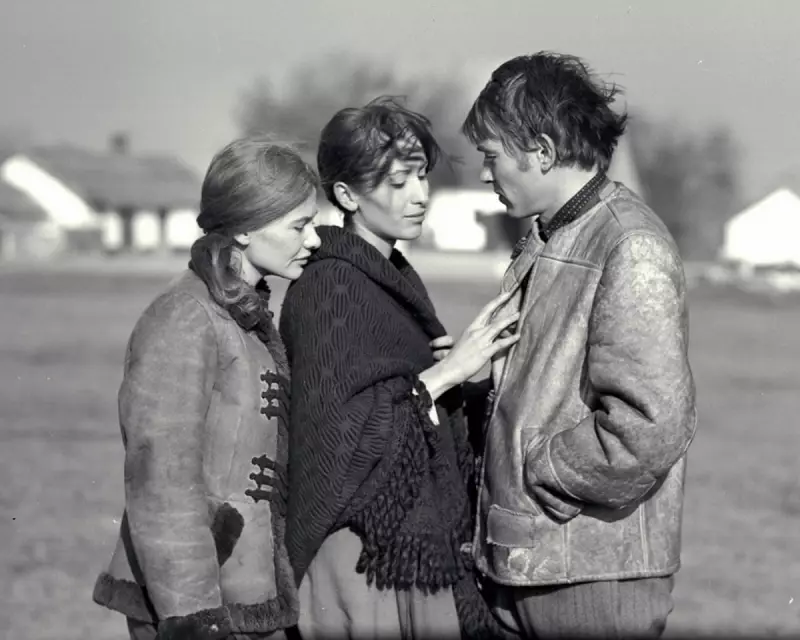

Set just after the First World War, the film is preceded by blurred archive photographs alluding to the nationalist government that overthrew the Hungarian Soviet Republic in 1919. This regime now pursues a vicious anti-Communist manhunt targeting Hungarian soldiers. One fugitive is István, portrayed by András Kozák, who hides on a farm owned by two sisters, Teréz and Anna, played by Mari Töröcsik and Andrea Drahota. Possibly driven mad by tension and isolation, the sisters are secretly poisoning Teréz's husband, Károly, and his elderly mother.

An army officer, Kémeri, aware of István's presence, appears to turn a blind eye. This negligence is exchanged for implied sexual favours from the women and, perhaps, because as a soldier, he cannot help but admire István's gallant war record. The film gradually reveals István's horror at the women's secret homicidal activities, forcing him to decide how to bring them to justice without endangering himself. Yet, this plot point is far from the film's central dramatic focus.

The Miasma of Fear and Ritualised Humiliation

What resonates more powerfully, moment by moment, is the pervasive miasma of fear and horror that settles over the landscape. Soldiers, led by a secret-police commandant in civilian clothing, menace the local populace. Houses are torn down as collective punishment, serving as a grim lesson in the consequences of non-cooperation. Wrongdoers, both military and civilian, are subjected to dehumanising treatments, such as standing in a yard for prolonged periods or performing exhausting "rabbit jumps."

In one particularly bizarre and harrowing ritual, the commandant forces Károly and other civilians to inspect two corpses—clearly killed by the authorities. They are made to touch the bodies, handle the dead men's personal effects like glasses, watches, and wallets, and then hold up their hands to an official photographer. This act ostensibly confirms their fingerprints on the items and their supposed guilt, but its true purpose is to humiliate, degrade, and intimately acquaint them with terror, underlining their fellowship with the defeated dead. In Silence and Cry, silence and the cry become one and the same—a unified expression of suffocating oppression.

Silence and Cry is available on Klassiki from 29 January, offering a renewed opportunity to engage with this haunting masterpiece of European cinema.