Can conceptual photography be genuinely funny? A major new group exhibition in London, titled 'Seriously', makes a compelling case that it can. Occupying four floors of the Sprüth Magers gallery, the show presents a riotous collection of still and moving images that deploy absurdity, slapstick, and wit to tackle weighty themes.

Feminist Wit and Visual Puns

The exhibition features a strong contingent of artists who used humour as a subversive tool in the 1970s and 1990s. Their work often takes aim at stifling gender norms and feminine stereotypes propagated by mass media and advertising. Sarah Lucas is captured brazenly chomping on a banana, while a suite of works by Cindy Sherman sharply satirises cinematic and media clichés of womanhood.

In one of Sherman's 2018 colour works, four heavily made-up figures in tulle gowns stare at the camera with unsettling expressions, seemingly seated in the sea. Meanwhile, Birgit Jürgenssen wears a ludicrous three-dimensional apron shaped like an oven, a potent visual pun on domestic confinement. This confrontational, spicy humour forms a core part of the show's political edge.

The Body as Absurd Object

Many artists in 'Seriously' explore the human body as a malleable, often ridiculous, form. Bruce Nauman's Studies for Holograms (1970) sees him pulling his face into grotesque and goofy shapes. In his L'Empereur series, German photographer Thomas Ruff throws himself around a drably coloured room, creating a moment of pure slapstick.

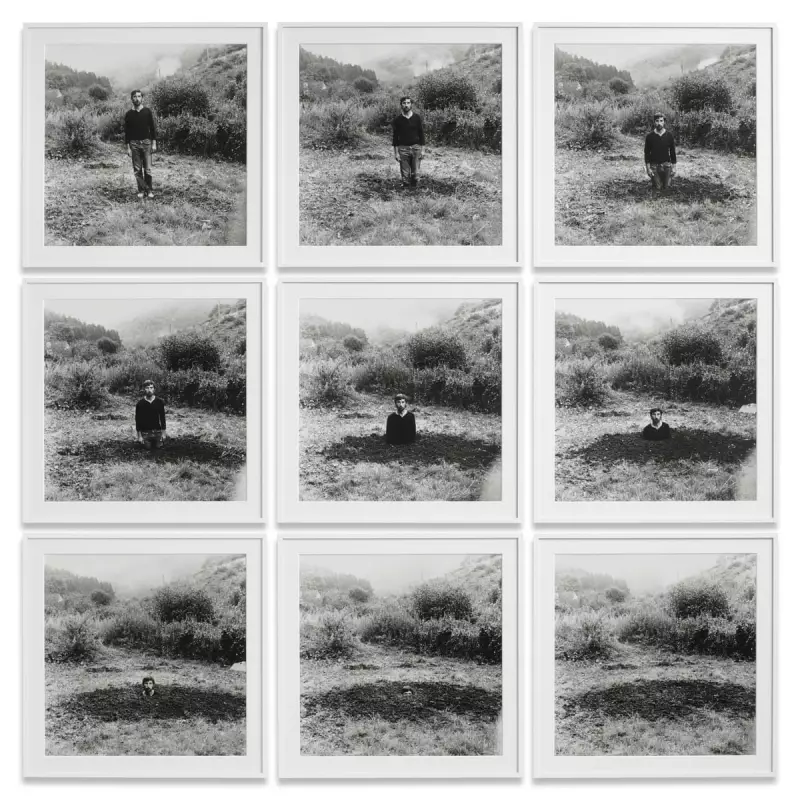

The exhibition also includes one of the most famous works of British conceptual art: Keith Arnatt's influential 1969 photo-sequence Self-Burial. Over nine images, the artist is seen gradually disappearing into a hole in the ground. The piece was originally broadcast on German television for a few seconds each night without explanation. While it might once have seemed a wry comment on an artist's vanishing act, it now carries a darker, universal resonance.

Laughing at Art and Media

Humour is also found in the parody of artistic conventions and media narratives. John Smith's brilliant 1976 film The Girl Chewing Gum is given a room to itself. In it, a voiceover appears to direct action on a London street, but is in fact narrating the movements of unwitting passersby with fantastical relish. The work feels eerily prescient in an age of fabricated narratives.

Louise Lawler's audio work Birdcalls (1972-81) screams the names of 28 famous male artists in bird-like shrieks, critiquing art-world sexism through absurdity. However, the exhibition acknowledges that humour is subjective and temporal; some gags may not land with modern audiences, and the dense art-historical references in certain pieces might be lost on some viewers.

Ultimately, 'Seriously' is less about provoking belly laughs and more about demonstrating how humour can be a powerful conceptual tool. It shows how artists used playfulness and wit to push photography beyond pure documentation into a more unstable and experimental realm. The exhibition runs at Sprüth Magers, London, until 31 January.