Eighteen months after Labour's manifesto pledge to halve violence against women and girls within a decade, the government has unveiled its flagship strategy: a £36 million programme introducing compulsory "anti-Andrew Tate" lessons in British schools. The move places the challenge of toxic misogyny front and centre in the national curriculum, targeting an attitude the Department for Education reports has reached "epidemic scale" among young people.

A Curriculum Front Against Toxic Influence

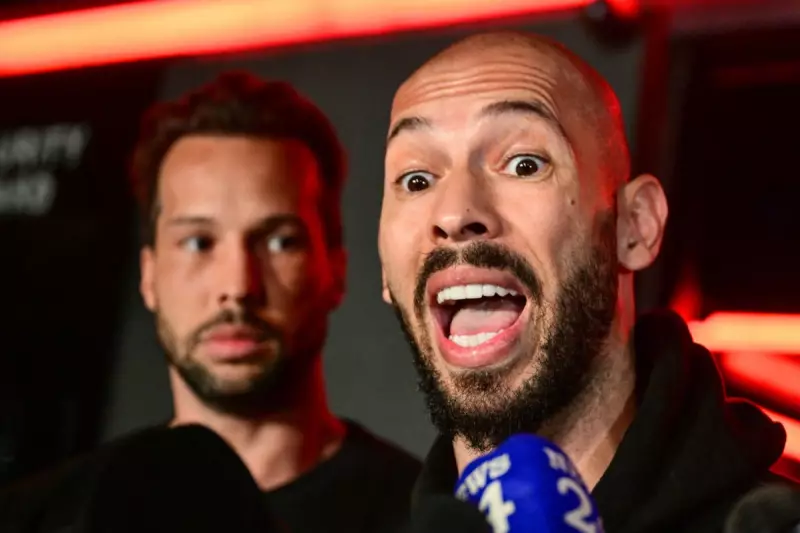

According to Jess Phillips, the government’s safeguarding minister, the new plans will focus on three core pillars: prevention by challenging misogyny, stopping abusers with enhanced police powers, and providing greater support for victims. A significant portion of this work will happen in the classroom. Children as young as 11 will be given compulsory courses on consent and lessons about the toxic influence of figures like self-confessed "misogynist" Andrew Tate.

The urgency is underscored by stark statistics. The National Police Chiefs' Council states that violence against women and girls constitutes just under a fifth of all recorded crime in England and Wales. In the year to March, around 12.8% of women experienced domestic abuse, sexual assault, or stalking. Perhaps most concerningly, a Girlguiding survey revealed 77% of girls and young women aged 7 to 21 experienced online harm in the last year, with more than one in five primary school-aged girls reporting they have "seen rude images" online—a figure that has doubled since 2021.

From Classrooms to a Self-Help Hotline

The educational drive will extend beyond standard lessons. Secondary school teachers will receive specialist training to discuss "healthy relationships," and there will be a push for frank conversations about violent pornography, including proposals to ban the depiction of strangulation. Children displaying signs of harmful behaviour will be enrolled in special programmes addressing coercion, peer pressure, and stalking.

Intriguingly, the government also proposes a "self-help"-style phoneline. This service would cater both to victims fearing they are in toxic relationships and to individuals worried about their own behaviours towards women. "I would be failing, we would be failing, if we didn't try to prevent people who were already perpetrating – and stopping people becoming perpetrators in the first place," Jess Phillips stated.

Why Schools Must Lead the Charge

While the strategy is broadly welcomed, its success hinges on execution. Critics point to the reluctance of many young men to discuss their feelings, with some teenagers expressing fear of "fuss" or embarrassment at the idea of therapy. However, this reluctance is precisely why proponents argue schools are the critical arena for normalising these conversations.

With Ofsted having reported a "scourge" of sexism in classrooms and 54% of 11 to 19-year-olds saying they have experienced or witnessed sexist comments, the need for institutional intervention is clear. The problem is compounded online; a leaked Home Office report identified the "manosphere" as a breeding ground for extremism, rife with misogynistic content that often absorbs right-wing extremist tropes.

As journalist Victoria Richards notes, education starts at home, but when that fails, the school system must step in. With over 40% of young men reportedly holding favourable views of Andrew Tate—who has publicly claimed women "bear responsibility" for rape and are a man's property—the mission to re-educate a generation has never been more pressing.