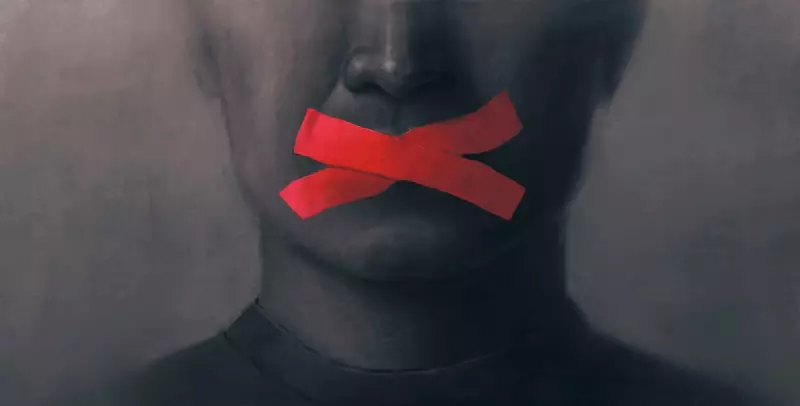

Australia's cultural landscape is at a crossroads, grappling with a profound challenge to the principle of free speech. The recent cancellation of the 2026 Adelaide Writers' Week, following a series of intense controversies, has exposed a critical failure among the nation's cultural custodians.

The Core Challenge: Defending the Indefensible

As award-winning journalist Margaret Simons contends, the essential task of defending an individual's right to speak, even when we find their views deeply objectionable, has proven extraordinarily difficult. For many, it can feel like a betrayal of personal values and community. Yet, Simons argues this is precisely the standard we must demand of those who steward our major cultural institutions—from the ABC and art galleries to writers' festivals and media boards.

Simons draws a stark contrast with a more perilous environment, recalling a writers' festival in Myanmar in 2015. There, former political prisoners shared space with those who had authored propaganda for the regime that jailed them. Despite daily threats of walkouts, the festival proceeded, dialogue occurred, and violence was avoided—a powerful testament to the possibility of difficult exchange.

What Free Speech Does—And Does Not—Mean

The debate hinges on a clear understanding of the principle. Simons examines two pivotal statements. In 2014, then Attorney-General George Brandis asserted in parliament that people have "the right to be bigots." Decades earlier, in 1982, Justice Lionel Murphy defended Indigenous activist Percy Neal's right to be an "agitator," quoting Oscar Wilde on the necessity of such figures for civilisational advance.

These statements illuminate the boundaries. Freedom of speech is a fundamental right, with widely accepted limits around incitement to violence or hatred. However, it is not a right to be respected, agreed with, or given a platform. A bigot may be entitled to their views, but cultural leadership involves making clear which speech is worthy of admiration and a privileged audience.

The Custodians' Burden: Judgment and Courage

This is where editors, directors, curators, and boards carry a greater responsibility than ordinary citizens. They must exercise wise judgment on who merits a platform and then possess the fortitude to uphold that decision under pressure. The recent failures at the ABC, in Bendigo, and in Adelaide stem from custodians who either misunderstood this role or were unequal to its demands.

Simons applies this to the current flashpoint. She describes author Randa Abdel-Fattah as an "agitator" in Murphy's sense—which she is entitled to be—and also a respected writer and academic, making her a reasonable festival invite. Similarly, while horrified by a particular column, she notes Thomas Friedman's Pulitzer Prize and New York Times tenure justified his 2024 invitation.

The hypocrisy, she notes, cuts both ways: pro-Palestinian activists seeking to de-platform Friedman while defending their own speech, and pro-Israel activists doing the same to Abdel-Fattah. For partisans, allowing the opposing side a platform feels like an assault on identity and cultural safety.

The crucial failure, however, lies with the custodians. Governments have been careless in appointments, treating board positions as rewards for cronies or selecting individuals who lack the requisite intellectual rigour, moral muscle, and courage. Culture is not necessarily nice, and niceness is not enough for this role.

The way forward is clear but arduous. Australia must appoint its best to these positions—individuals capable of the extraordinary judgment and courage required. On their shoulders rests the health of the national conversation, the robustness of democracy, and the very character of the country.