New reports have revealed that a female IRA commander, identified as a key suspect in the 1987 Enniskillen bombing, has evaded justice for nearly four decades. This stands in stark contrast to the ongoing legal pursuit of British soldiers who served during the Troubles.

Details of the Attack and Suspect

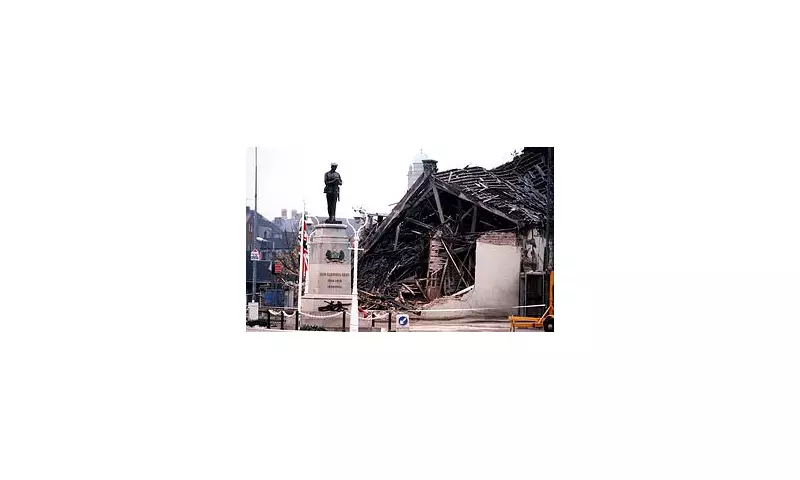

The horrific incident occurred on Remembrance Sunday in 1987 in the town of Enniskillen. A bomb, detonated by a timer, exploded at a community centre, killing 12 people and injuring more than 60. It remains one of the bloodiest single attacks of the conflict.

According to details from a Times podcast, The Poppy Day Bomb, the female suspect was seen wearing a green dress and carrying a brown paper bag outside the centre just before the explosion. Police identified her as the leader of an IRA cell responsible for the attack.

She is believed to have fled to the United States shortly after the bombing, living abroad for a period before returning to Northern Ireland. Shockingly, she has reportedly been seen in Enniskillen in recent months.

A 37-Year Search for Justice

Despite 13 arrests over the years, no one has ever been successfully prosecuted for the Enniskillen atrocity. The IRA later admitted responsibility, stating it ‘deeply regretted’ the event, but this offered little solace to the bereaved families.

The Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) and its successor, the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI), have conducted multiple case reviews without bringing charges. Furthermore, the UK government has consistently rejected calls for a public inquiry into whether intelligence failures could have prevented the loss of life.

For the families of the victims, the past 37 years have been a relentless quest for truth and accountability, a quest that remains unfulfilled as many suspects are thought to still live locally.

Contrast with Treatment of Security Forces

These revelations emerge amidst fierce controversy over the legal treatment of former security force personnel. The previous government's Legacy Act provided qualified protections against prosecution for police officers and soldiers involved in the Troubles.

However, the Labour government has repealed this act, replacing it with new legislation—the Troubles Bill—which removes those specific safeguards. The actions of RUC and Army personnel are now being assessed under the 1998 Human Rights Act, opening the door to retrospective prosecutions.

This policy shift has sparked significant backlash. An online petition against the removal of protections for veterans garnered over 210,000 signatures. Reports suggest as many as 100 SAS soldiers could now face legal action.

The government defends its position, stating the old Legacy Act was ruled unlawful and failed to offer real protection. A spokesperson said the new bill provides ‘six lawful and deliverable protections designed in consultation with veterans’.

Nevertheless, the contrasting fates—a prime suspect walking free while veterans face court—has become a focal point for critics, highlighting the enduring complexities and raw wounds of Northern Ireland's past.