Justice Crisis Sparks Controversial Jury Trial Overhaul

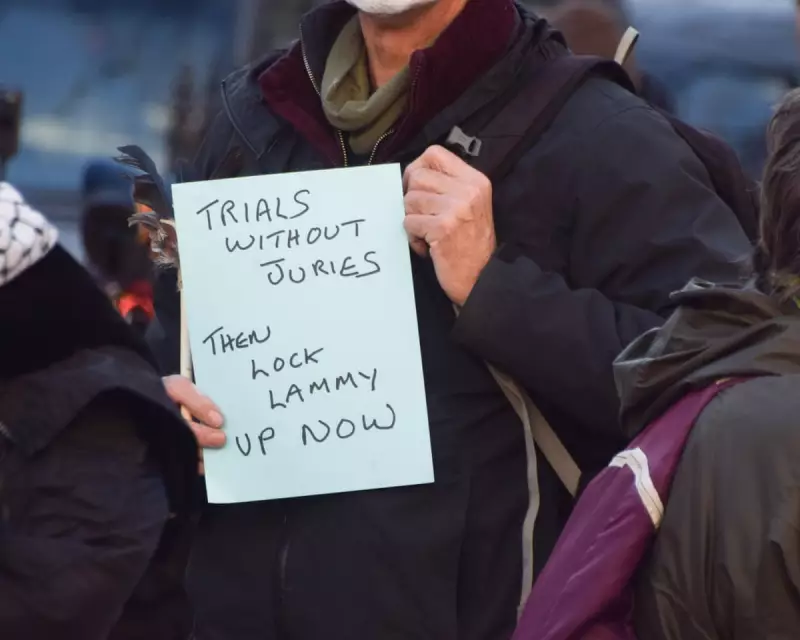

The UK's justice system faces unprecedented pressure as leaked proposals from Justice Secretary David Lammy suggest dramatically reducing jury trials. The plan, revealed in November 2025, would limit jury trials to only the most serious cases including rape, murder and offences carrying sentences longer than five years.

This radical move comes as the courts grapple with a massive backlog that has seen some victims told they must wait until 2029 for their cases to be heard. Both victims and defendants are suffering under a system where justice is increasingly delayed, with witnesses' memories fading and lives being put on hold indefinitely.

The Case For and Against Jury Trials

Supporters of Lammy's proposal point to genuine concerns about the current system. Jury trials account for just 1% of criminal cases in England and Wales, yet they consume significant court resources. Critics highlight instances where juries have struggled with complex evidence, such as in medical cases like the Lucy Letby conviction, where expert doubts have been raised about jury comprehension of technical details.

However, defenders of the jury system argue it remains fundamental to justice being seen to be done. As Lady Helena Kennedy KC noted, public confidence in institutions depends on public involvement. For many citizens, jury service represents their only direct experience with the legal process, providing crucial transparency.

Broader Implications for Justice and Democracy

The debate extends beyond practical considerations to fundamental questions about democracy and rights. Juries serve as a vital safeguard against both racism and the politicisation of courts. Twelve people with competing biases may collectively cancel out individual prejudices more effectively than a single judge, however well-trained.

Lammy's proposals follow recommendations from Sir Brian Leveson KC's review, which suggested creating juryless divisions and allowing judges to hear complex cases alone. However, Leveson's terms of reference explicitly required considering financial constraints, leading critics to argue this represents justice on the cheap rather than genuine reform.

The underlying issue remains chronic underfunding across the justice system and related public services. Delays in obtaining mobile phone data, probation reports and social worker assessments all contribute to the backlog, as does the growing complexity of laws and more proactive policing of historical sexual abuse cases.

As with other public services like the NHS, the judicial backlog represents the legacy of previous governments' spending choices. The current administration faces the challenge of clearing this backlog without compromising the fundamental principles of British justice that have stood for centuries.