Stonehenge's Ancient Enigma Unravelled by Microscopic Evidence

The enduring 5,000-year-old mystery surrounding Stonehenge's construction appears to have been conclusively resolved, thanks to groundbreaking analysis of minuscule sand grains. While competing theories have long debated whether the monument's colossal stones were dragged by Neolithic builders or transported by glaciers, new scientific evidence strongly supports human endeavour as the definitive answer.

The Glacial Transport Theory Challenged

For decades, a significant school of thought proposed the glacial transport theory, suggesting that ice sheets covering ancient Britain conveniently carried the megaliths from Wales and Scotland to the Salisbury Plain. This hypothesis emerged because the alternative—Neolithic people moving multi-tonne stones hundreds of miles with primitive tools—seemed implausible to some researchers. However, a meticulous geological investigation has now delivered compelling counter-evidence.

Geologists from Curtin University employed state-of-the-art mineral fingerprinting techniques to examine the landscape. Their research focused on a critical premise: if glaciers had indeed transported the stones, they would have deposited a detectable trail of microscopic mineral grains across the region. Specifically, the ice would have left behind vast quantities of sand and gravel with distinctive age signatures in local rivers and soils.

Mineral Clocks and Geological Fingerprints

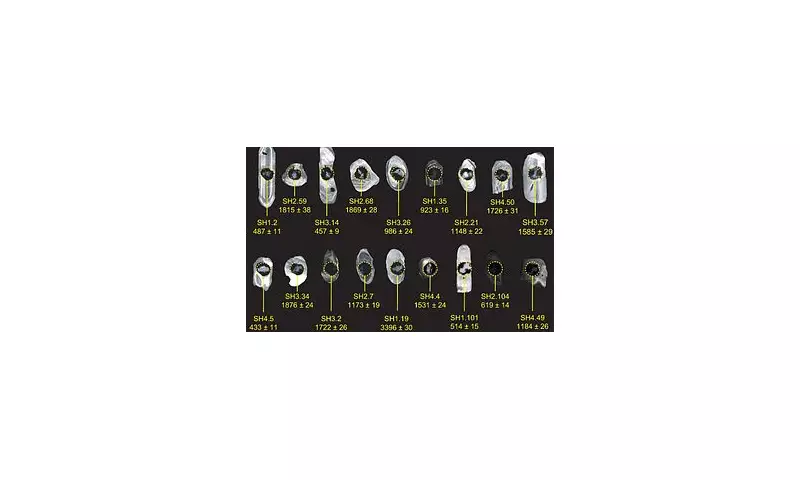

The study centred on two key minerals—zircon and apatite—which function as precise geological chronometers. When these minerals crystallise from magma, they trap radioactive uranium that decays into lead at a known, constant rate. By measuring the uranium-to-lead ratio in individual grains, scientists can determine their formation age, creating a unique geological fingerprint for different rock sources across Britain.

Dr Anthony Clarke, the lead author, explained the methodology: "Because Britain's bedrock has very different ages from place to place, a mineral's age can indicate its source. This means that if glaciers had carried stones to Stonehenge, the rivers of Salisbury Plain should still contain a clear mineral fingerprint of that glacial journey."

Definitive Findings from Salisbury Plain Sediments

The research team analysed over 700 zircon and apatite grains collected from rivers near Stonehenge. The results were decisive. The zircon grains dated from 2.8 billion to 300 million years ago, covering nearly half of Earth's history, yet almost none matched the age profiles of the bluestones' Welsh origins or the altar stone's Scottish source.

Instead, most zircon grains clustered between 1.7 and 1.1 billion years ago, correlating with the Thanet Formation—a layer of loosely compacted sand that historically covered southern England. Meanwhile, all apatite grains dated to approximately 60 million years ago, a period when tectonic activity from the Alps' formation reset their uranium clocks, indicating long-term local presence rather than recent glacial import.

Co-author Professor Chris Kirkland summarised: "Salisbury Plain's sediment story looks like recycling and reworking over long timescales, rather than a landscape built from major glacial imports. The material around Stonehenge doesn't have a clear signal from those points of origin, so we conclude Salisbury Plain remained unglaciated during the Pleistocene, making direct glacial transport of the megaliths unlikely."

Reaffirming Neolithic Ingenuity

This evidence robustly supports the established archaeological view that Neolithic communities undertook the monumental task of transporting the stones. The bluestones, weighing two to five tonnes, were sourced from the Preseli Hills in Wales, while the six-tonne altar stone originated in northern Scotland, over 460 miles away. Their transportation would have required sophisticated methods, including sledges, rollers, prepared trackways, and possibly river and coastal routes using boats.

Professor Kirkland reflected on the implications: "You could propose a coastal movement by boat for the long legs, then final overland hauling using sledges, rollers, prepared trackways, and coordinated labour. If you think about this, it supports the idea of an advanced connected society in the Neolithic."

Stonehenge's Construction Phases

The Stonehenge visible today represents the culmination of a complex, multi-stage building project:

- First Stage (c. 3100 BC): Initial earthwork comprising a ditch, bank, and the Aubrey holes, likely used for ceremonial purposes.

- Second Stage (c. 2150 BC): Transportation of approximately 82 bluestones from Wales, involving a 240-mile journey via rollers, sledges, and rafts.

- Third Stage (c. 2000 BC): Arrival of the larger sarsen stones from the Marlborough Downs, arranged in an outer circle with lintels and inner trilithons.

- Final Stage (post-1500 BC): Rearrangement of bluestones into the iconic horseshoe and circle formations that endure today.

This research not only solves a longstanding archaeological puzzle but also highlights the remarkable capabilities of Neolithic societies, whose determination and ingenuity enabled the creation of one of Britain's most iconic prehistoric monuments.