Revolutionary Theory Suggests Internal Pulley System Built Great Pyramid

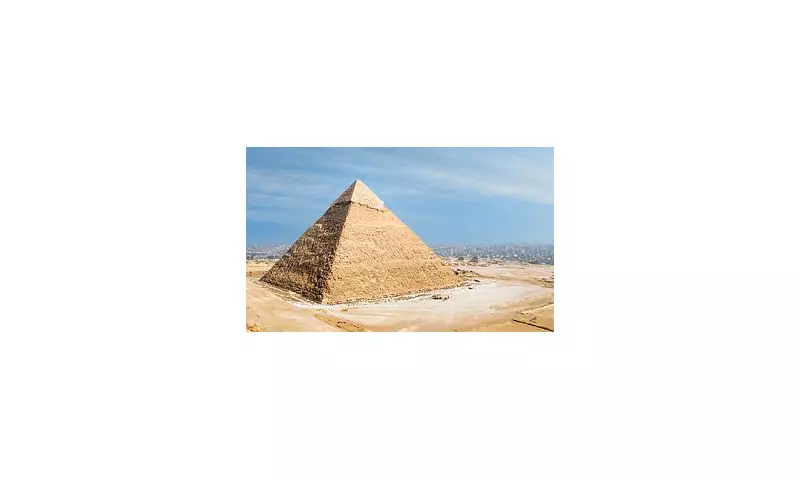

The enduring mystery surrounding the construction of Egypt's Great Pyramid has captivated archaeologists and historians for centuries, with no surviving ancient texts explaining precisely how its colossal stone blocks were lifted and assembled with such remarkable speed and precision. Traditional theories have long relied on the concept of external ramps and a gradual, layer-by-layer construction process, yet these explanations have consistently struggled to account for how stones weighing up to sixty tons could be raised hundreds of feet in a mere two decades.

Counterweight Mechanism Proposed in New Research

Now, a transformative new study published in the prestigious journal Nature has proposed a radical alternative: the pyramid was constructed using an ingenious internal system of counterweights and pulley-like mechanisms cleverly concealed within its very structure. Dr Simon Andreas Scheuring of Weill Cornell Medicine in New York conducted detailed calculations suggesting that builders could have lifted and positioned massive blocks at an astonishing pace, potentially as quickly as one block per minute.

He argues that such rapid construction would only have been feasible with sophisticated sliding counterweights, rather than relying solely on brute-force hauling by labourers. This mechanical approach would have generated the necessary power to raise stones to the upper levels of the Pyramid of Khufu efficiently.

Architectural Features Reinterpreted as Engineering Elements

The study meticulously re-examines key architectural features inside the pyramid, identifying the Grand Gallery and Ascending Passage not as ceremonial corridors but as sloped ramps where counterweights may have been deliberately dropped to create a powerful lifting force. Furthermore, the Antechamber—traditionally interpreted as a security feature designed to thwart tomb robbers—is reinterpreted as a crucial pulley-like mechanism that could have assisted in lifting even the heaviest blocks.

If this theory holds true, it suggests the Great Pyramid was constructed from the inside out, beginning with an internal core and employing hidden pulley systems to raise stones progressively as the structure expanded upwards. This represents a fundamental shift from conventional understanding of ancient Egyptian construction methodologies.

Detailed Evidence from the Pyramid's Interior

The Great Pyramid of Khufu, the oldest and largest of the Giza pyramids, was built as a tomb for Pharaoh Khufu around 2560 BC, approximately 4,585 years ago. Despite its age, it remains the world's only Ancient Wonder still largely intact and is renowned for its precise construction from millions of stone blocks and its complex internal passages leading to the King's Chamber.

According to Dr Scheuring's research, heavy counterweights sliding downward along these sloped internal passages would have generated sufficient force to lift blocks upward elsewhere in the core. He points to specific physical evidence within the Grand Gallery, including scratches, wear marks, and polished surfaces along its walls, indicating that large sledges moved repeatedly along its length. This pattern suggests mechanical stress consistent with sliding loads rather than foot traffic or ritual use.

The Antechamber as a Functional Lifting Station

The study offers a particularly compelling new explanation for the Antechamber, a small granite room situated just before the King's Chamber. Grooves cut into its granite walls, stone supports that may have held wooden beams, and unusually rough workmanship all point towards a functional machine rather than a finished ceremonial room. In Scheuring's reconstruction, ropes would have run over wooden logs set into the Antechamber, enabling workers to lift stones weighing up to sixty tons.

This system could apparently be adjusted to increase lifting power when required, operating similarly to changing gears in a modern mechanism. Oversized rope grooves and an uneven, inlaid floor further suggest the chamber was once connected to a vertical shaft that was sealed once construction concluded.

Engineering Compromises Over Symbolic Design

Beyond individual rooms, Scheuring argues that the pyramid's entire internal layout reflects practical engineering compromises rather than purely symbolic design. Major chambers and passages cluster near a shared vertical axis but are curiously offset rather than perfectly centred. For instance, the Queen's Chamber is centred north–south but not east–west, while the King's Chamber sits noticeably south of the pyramid's central axis.

Such irregularities are difficult to explain if the pyramid was built neatly from the ground up using external ramps, where builders could theoretically have placed chambers with perfect symmetry. Instead, these offsets suggest builders were working around mechanical constraints imposed by internal lifting systems, lending credence to the new theory.

Explaining External Features and Future Predictions

The theory also provides plausible explanations for puzzling exterior features, including the slight concavity of the pyramid's faces and the complex pattern in which stone layers gradually change height. According to Scheuring, these characteristics may reflect how internal ramps and lifting points shifted as the pyramid rose and stones became lighter at higher levels.

Importantly, this new model makes testable predictions. It suggests no large undiscovered chambers remain hidden in the pyramid's core, an idea supported by recent muon-scanning surveys. However, smaller corridors or remnants of internal ramps may still exist in the outer portions of the structure, particularly at higher elevations. If supported by future archaeological discoveries, Dr Scheuring's proposal could fundamentally reshape how scholars understand not only the Great Pyramid but pyramid construction across ancient Egypt as a whole.