As the festive season reaches its peak, millions of households across the UK are unwittingly inviting a tree-killing parasite into their living rooms. The plant in question is mistletoe, a festive staple more commonly associated with stolen kisses than with ecological harm or health risks.

The Parasitic Nature of a Festive Icon

Far from being a harmless decoration, mistletoe is scientifically classified as a hemiparasite. Entomologist Bill Reynolds describes it as the 'thief of the tree'. It cannot grow in soil and survives solely by attaching to host trees with root-like structures, siphoning off vital water and nutrients. This process can weaken and sometimes even kill the host tree.

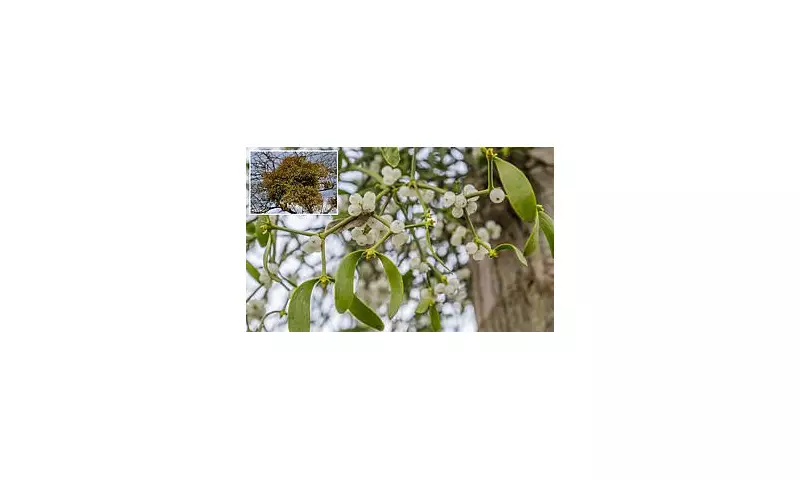

The plant is identifiable by its round, green clusters that cling to bare branches in winter, long after the host tree has lost its leaves. While this appearance may seem magical, its parasitic mechanism is remarkably efficient and, more importantly, its toxicity poses a direct risk to humans and animals.

A Toxic Threat to Children and Pets

The cheerful holiday plant carries a hidden danger: it is mildly toxic. If ingested by curious children or pets, it can cause significant gastrointestinal distress, including stomach pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhoea.

Consuming as few as five berries or leaves can be enough to trigger these symptoms in people. The American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) officially lists mistletoe as toxic and advises pet owners to contact a veterinarian immediately if their dog or cat consumes any part of the plant.

From Ancient Remedy to Victorian Tradition

Despite its problematic nature, mistletoe's place in our winter celebrations is deeply rooted in history. The tradition of kissing under it dates back to 18th century Victorian England. The Victorians popularised the custom of a seasonal kiss beneath the bough, a practice that spread to the United States in the 19th century.

Its history stretches back much further, however. Ancient Greeks and Romans used the berries for purposes ranging from birdlime to ointments for skin ulcers. The plant was also considered sacred by Celtic Druids. In 1820, author Washington Irving wrote that each berry plucked from the mistletoe represented a kiss a young man could bestow, with the privilege ending once all berries were gone.

Reynolds notes that as a hemiparasite, mistletoe does engage in some self-sustaining processes like photosynthesis. Its presence is not entirely negative for ecosystems. Birds including robins, bluebirds, and mourning doves nest in its dense foliage and eat its fruit, inadvertently spreading the seeds to new trees. Creatures like squirrels, chipmunks, and deer also feed on it.

Recent research, including a survey of urban forests in seven western Oregon cities, found little connection between mistletoe infestation and negative tree health. Professor emeritus Dave Shaw, a forest health specialist, suggested that 'Western oak mistletoe is probably a benefit to wildlife in urban forests', though he acknowledged potential negative impacts on amenity trees that require careful management.

Ultimately, while mistletoe may rarely kill its host tree, the debate about its harm continues among experts. For households this December, the primary concern remains its toxicity, turning a symbol of festive affection into an item requiring cautious placement well away from children and pets.