The Day I Saw My Grandmother's Ghost in a Coffee Shop

During my mid-twenties, I experienced something that stopped me in my tracks. Peering through a coffee shop window, I saw my grandmother sitting calmly inside. The shock was profound - she had passed away the previous year. For a moment, time stood still before reality reasserted itself, reminding me this couldn't possibly be her.

This wasn't an isolated incident. Throughout my life, I've frequently "recognised" complete strangers. Sometimes I could quickly identify who they reminded me of, like my grandmother. Other times, faces simply carried a vague familiarity I couldn't quite place.

When I began asking friends about their experiences, responses varied dramatically. One friend regularly sees familiar faces in random places. Others occasionally mistake strangers or celebrities for people they know. Yet some reported nothing of the sort - they could easily distinguish between people they'd met and complete strangers.

The Science Behind Facial Recognition Spectrum

This range of experiences led me to explore the science of facial recognition. Researchers have developed numerous tests to measure our ability to remember faces, revealing a broad spectrum of capability. At one extreme are super-recognisers who can remember faces seen only briefly or long ago. At the other end are people with face blindness (prosopagnosia) who often struggle to recognise family members, close friends, and even themselves.

Joseph DeGutis, a cognitive neuroscientist at Harvard Medical School, explained that while much research focuses on remembering faces, less attention has been paid to our ability to discern unfamiliar faces. "Researchers just haven't dug into this as much," he noted. Evidence suggests these two skills use different brain processes, with super-recognisers and prosopagnosics performing similarly at identifying new faces despite their vastly different abilities to recall familiar ones.

Testing My Own Facial Recognition Abilities

Curious about where I fell on this spectrum, I completed several facial recognition tests provided by DeGutis. The Cambridge Face Memory Test required me to study black-and-white face photos from three angles, then identify them in lineups. Another test involved picking celebrities from mixed photos - many felt vaguely familiar but I couldn't quite place them, mirroring my real-life experiences.

Despite feeling uncertain about my performance, the results surprised me. I correctly identified 96% of celebrity faces, with DeGutis concluding I was a "borderline super-recogniser." In the old/new faces task - particularly effective for assessing facial memory - I remembered 78% of previously seen faces, just shy of the super-recogniser cutoff of 80%. People with prosopagnosia average only 57% on this test.

Most intriguing was my false alarm rate of 18% - significantly lower than the average 30% for normal recognisers, super-recognisers, and prosopagnosics. This raised the question: why was I mistaking strangers for my grandmother if I rarely confused new faces in tests?

The Hyperfamiliarity Phenomenon

DeGutis theorised that I possess some super-recogniser capabilities. Like super-recognisers, I probably maintain a relatively large, high-resolution catalogue of familiar faces in my memory. We also tend to individuate faces, assigning traits like friendliness or rudeness to each one. Studies suggest this helps commit faces to long-term memory but might also trick me into seeing my grandmother in someone with a similar demeanour.

Furthermore, DeGutis suggested I might be "an active face perceiver," paying considerable attention to faces. While others might have more false recognition moments, my close observation makes me more likely to notice strangers resembling people I know. One friend who rarely makes recognition mistakes admitted she doesn't really look at people around her.

Research led me to hyperfamiliarity for faces (HFF), a condition where unfamiliar faces appear familiar. However, the handful of reported cases all followed medical episodes like seizures or strokes, unlike my lifelong experiences.

When Every Face is Familiar: Jenny's Story

Brad Duchaine, a professor at Dartmouth College who runs faceblind.org with colleagues, has heard from only a few possible HFF cases in 25 years. "The prevalence is quite low," he said, though he theorises there might be a spectrum, with some people experiencing it constantly and others, like me, only occasionally.

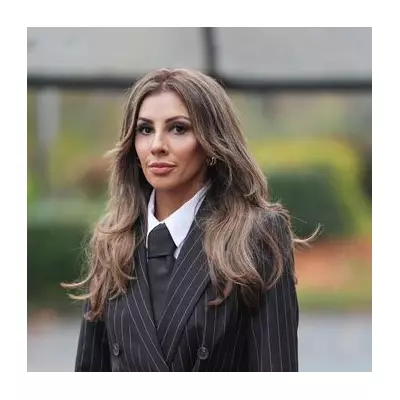

Jenny, a 53-year-old zookeeper in northern England, developed HFF in 2018 after unusual migraines. Visiting a seaside town she'd rarely been to before, every person on a tram looked familiar. Even back home, she was convinced she knew everyone passing by, sometimes following them to figure out who they were.

"Many times I would walk up to someone and smile, and they just walked past me," Jenny recalled. "Obviously it was a massive change." Her condition became so overwhelming she dreaded leaving home for two years.

In a fascinating experiment using Game of Thrones clips and fMRI scans, researchers discovered that although Jenny had never seen the show, her brain activity in the medial temporal lobe - involved in recognising familiar faces - resembled that of viewers who had. The actors evoked feelings similar to strangers on the street: "It was like I had memories with them, which I was looking at through a frosted window."

The Social Impact of Facial Recognition Differences

While my experiences are manageable, about 2% of the population has prosopagnosia, with clear links to social anxiety, according to Anna Bobak, a psychology senior lecturer at the University of Stirling.

People with face blindness feel "anxiety or fear about negative evaluations from others" who might think they're being rude or aloof for not recognising acquaintances, Bobak explained. Recent surveys reveal they develop detailed recall methods, like memorising specific jewellery, and primarily wish for greater awareness and reasonable adjustments similar to those for autism and ADHD.

Facial recognition remains poorly understood because the roles of vision, memory, and emotion are still unclear. While super-recognisers may have more brain activity in visual regions processing faces and prosopagnosics less, the Game of Thrones research highlights how emotion and memory regions connect with visual areas.

Duchaine plans new studies exploring whether these regions contribute to facial recognition differences in super-recognisers and prosopagnosics. Understanding why false alarm moments occur could shed light on conditions like HFF.

Embracing the Quirk of Familiar Strangers

Reflecting on DeGutis's suggestion that I might be particularly attuned to facial emotions, I realise I sometimes mistake strangers for acquaintances because they share similar "vibes" or demeanours. Once, an Amtrak agent so resembled my favourite bartender that I expected a cocktail rather than a ticket. Beyond physical similarities, they shared a cool nonchalance.

I wouldn't change my tendency to recognise strangers. I enjoy observing faces and detecting familiar features or atmospheres. While sometimes disorienting, solving the puzzle of who they remind me of feels illuminating and grounding. It's as if I understand both the stranger and the familiar person more deeply.

Now more aware of this quirk, I sometimes enter coffee shops or bars wondering if I'll encounter a stranger I know. Like Jenny, despite our different experiences, we agree that seeing a familiar face can be comforting, even if it's merely a mirage created by our remarkable, complex brains.