Archaeologists have confirmed the existence of a colossal, lost ring of ancient pits near Stonehenge, a discovery now hailed as likely the largest prehistoric structure in all of Britain.

A Monumental Discovery in the Salisbury Plain

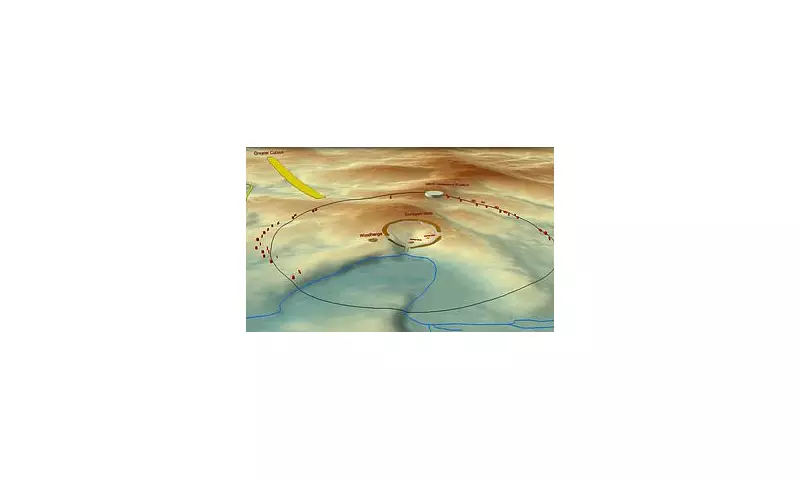

This vast formation consists of more than 20 enormous pits, some measuring a staggering 10 metres deep and five metres wide. Arranged in a sweeping arc, the ring extends for more than a mile across the landscape. At its very centre lie the ancient henge sites of Durrington Walls and Woodhenge, located 1.8 miles northeast of the famous Stonehenge monument.

Researchers, employing a suite of novel scientific techniques, have now determined that these pits were likely constructed by Neolithic people around 4,500 years ago. The sheer scale of the work involved in carving these features into Wiltshire's chalky ground would have required an immense communal effort and sophisticated planning.

Scientific Proof of Human Origins

Initially discovered in 2020, the pit circle was immediately recognised as one of Britain's most significant ancient sites. However, a key question remained: were these features man-made or natural formations? A new research paper, titled 'The Perils of Pits', led by Professor Vincent Gaffney from the University of Bradford, presents conclusive evidence for their human origins.

To solve the mystery, scientists deployed an array of cutting-edge methods. They first used electrical resistance tomography to map the underground structures. This was supplemented with radar and magnetic imaging to assess their depth and shape. To go beyond mere morphology, the team extracted sediment cores for detailed analysis.

Using optically stimulated luminescence, they determined the last time the soils were exposed to sunlight. They also employed novel geochemistry and extracted ancient sedimentary DNA (sedDNA) directly from the earth. The results were unequivocal: each pit showed an identical, repeating pattern of soil layers starting in the late Neolithic period—a pattern extremely unlikely to occur naturally.

Furthermore, the analysis identified the DNA of cattle and sheep within the pits, suggesting the area was occupied and farmed at the time of their creation.

Redefining Neolithic Britain

This confirmation solidifies the pit circle's status as a purposefully constructed monument. Professor Gaffney describes the vast structure as a 'cosmological statement' that inscribed a boundary into the landscape, setting apart an area of special significance. It linked the Durrington Walls henge with an earlier causewayed enclosure at Larkhill.

The discovery has profound implications for our understanding of Neolithic society. 'The size of the structure demonstrates the society they lived in was capable of planning and motivating large numbers of people for religious purposes,' Professor Gaffney stated. The near-perfect circular layout, which cannot be seen across due to its size, suggests the builders laid it out by pacing, implying the use of a numerical system for counting. This could represent some of the earliest evidence for counting ability in Neolithic Britain.

While we may never know the exact ritual purpose of these vast pits, this lost ring forever changes our perception of the ambition and organisational skills of Britain's ancient inhabitants.