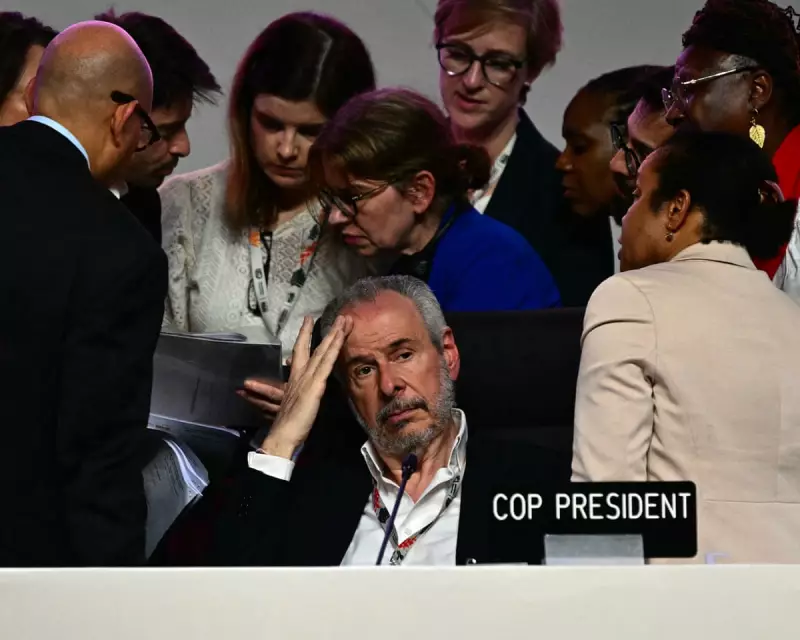

The world has not yet lost the battle against the climate crisis, the UN's top climate official declared, following the conclusion of a fiercely contested Cop30 summit that culminated in a hard-won agreement.

Simon Stiell, the UN climate chief, stated that while the global community is not winning the fight against dangerous global heating, it remains actively engaged in the struggle. The summit, held in Belém, Brazil, navigated what Stiell described as "stormy political waters" marked by denial, division, and geopolitics.

A Fractured Path to Agreement

Reaching a consensus proved exceptionally difficult, with negotiations threatening to collapse on Friday before a compromise was finally brokered on Saturday. The final deal emerged from an atmosphere of bitter opposition from some countries, led by Saudi Arabia, which successfully blocked efforts to formally plan a transition away from the fossil fuel age.

Furthermore, a key ambition for the Amazon-hosted conference – to chart a definitive end to deforestation – was significantly underdelivered. Proposals on both fossil fuels and deforestation were moved to processes outside the UN framework, to be advanced by coalitions of willing nations.

Despite these setbacks, the fact that the talks did not collapse was hailed as a victory for multilateralism in a fractious global era. "Climate cooperation is alive and kicking," Stiell asserted, making an oblique reference to the absence of the United States, which under Donald Trump did not send a delegation.

Key Outcomes and Glaring Omissions

The Cop30 package included decisions on numerous issues. Notably, it produced a promise to triple adaptation funding to help communities withstand climate impacts, established a just transition mechanism (JTM), and, for the first time, formally recognised the land rights and knowledge of Indigenous peoples as a fundamental climate solution.

However, the final text faced severe criticism for its shortcomings. The deadline for the increased adaptation finance was pushed back to 2035, a move criticised by frontline communities. There was no direct reference to fossil fuels in the final agreement, a point lamented by scientists and activists alike.

Emil Gualinga, of the Kichwa Peoples of Sarayaku, Ecuador, noted that despite Brazil branding it the "Indigenous Cop," participation for Indigenous groups remained limited. The impacts of the global food system on climate change were also largely ignored.

Relief and Disappointment from Global Observers

The overall sentiment was one of relief that a deal was reached, but deep disappointment in its lack of ambition. Anna Åberg from Chatham House commented that a "Cop collapse would have been a big and harmful blow" to international cooperation.

This view was echoed by the EU commissioner for the environment, Wopke Hoekstra, who called the outcome "a huge step in the right direction," albeit imperfect. UN Secretary-General António Guterres warned that the gap between current actions and scientific demands remains "dangerously wide."

Civil society made its presence strongly felt in Belém, with a major march of tens of thousands of protesters. Jamie Henn of Fossil Free Media noted a "palpable sense of momentum that I haven't felt for years."

Looking ahead, Professor Michael Grubb of University College London suggested that the focus must shift from the negative—phasing out fossil fuels—to the positive economic potential of accelerating the renewable energy transition, paving the way for Cop31.