The Toxic Legacy of America's Carpet Empire

A comprehensive new investigation has uncovered the devastating environmental and health consequences of America's multibillion-dollar carpet industry, revealing how chemicals used for decades to create stain-resistant products have contaminated vast areas of the American South.

The Showdown That Changed Nothing

In a pivotal 2000 meeting that foreshadowed decades of inaction, Bob Shaw, CEO of the world's largest carpet company, confronted executives from chemical giant 3M. Holding up a carpet sample bearing the Scotchgard logo, Shaw declared it "a target" rather than a brand identifier. Weeks earlier, 3M had announced it would reformulate its signature stain-resistance product under pressure from the Environmental Protection Agency due to mounting health and environmental concerns.

"I got 15 million of these out in the marketplace," Shaw reportedly told his visitors. "What am I supposed to do about that?" When a 3M executive admitted he didn't know, Shaw threw the sample at him and stormed out. This confrontation would prove emblematic of the industry's response to growing evidence about the dangers of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), commonly known as forever chemicals.

Decades of Contamination

For years, carpet manufacturers continued using closely related chemical alternatives even as scientific studies and regulators warned about their accumulation in human blood and potential health effects. The industry's massive scale meant millions of pounds of these chemicals entered the environment through manufacturing processes in northwest Georgia, eventually reaching river systems that provide drinking water to hundreds of thousands of people across Georgia and eastern Alabama.

Researchers have now identified the region as one of America's most significant PFAS hotspots. These persistent chemicals, which can take decades or more to break down, have been detected in water supplies, soil, household dust where children crawl, local wildlife, and increasingly, in human blood samples.

Human Cost of Industrial Success

The investigation reveals how Dalton, Georgia, proudly known as the "Carpet Capital of the World," became ground zero for this contamination crisis. Fleets of semitrucks bearing company logos rumble from behemoth warehouses in a city where textiles have employed generations, transforming 19th-century cotton mills into a global manufacturing hub.

Dolly Baker, a lifelong Calhoun resident, recently learned her blood contains PFAS levels hundreds of times above the U.S. average. "I feel like, I don't know, almost like there's a blanket over me, smothering me that I can't get out from under," she described. "It's just, you're trapped."

Medical professionals like Dr. Katherine Naymick, who has practiced in Calhoun since 1996, report mystifying patterns of illness among patients, including unusually high rates of thyroid problems and endocrine cancers. "Doctors have few tools to address patient concerns," she explained, noting that understanding of these chemicals' health effects is still evolving.

Industry Knowledge and Regulatory Failure

Court records and internal documents reveal that carpet industry leaders had early warnings about PFAS dangers. As early as 1998-1999, 3M held meetings with executives from Shaw Industries and Mohawk Industries to disclose research showing Scotchgard chemicals accumulating in human blood and persisting in the environment.

Despite this knowledge, the industry benefited from regulatory inaction. A lack of state and federal regulations allowed companies to legally switch between different versions of stain-resistant products while maintaining production. Meanwhile, Dalton Utilities, the local public water authority, coordinated privately with carpet executives in ways that effectively shielded companies from oversight.

Cozy Relationships and Resistance to Oversight

The investigation uncovered a deeply intertwined relationship between the carpet industry and local regulators. Carpet executives have long sat on Dalton Utilities' board, appointed by the city's mayor and council. In 2004, when EPA representatives sought access to facilities for water testing, industry and utility officials resisted strongly.

"Dalton Utilities has said not no, but hell no," Shaw's director of technical services told colleagues about allowing testing, according to meeting notes. The utility and industry feared test results could lead to "inaccurate public perceptions and inappropriate media coverage."

Scientific Warnings Ignored

University of Georgia research published in 2008 made headlines when it reported PFAS levels in the Conasauga River were "among the highest ever recorded in surface water" worldwide. The study prompted the carpet industry to create a crisis management team while downplaying concerns.

"In our society today, it is absolutely known that you report the presence of some chemical and everybody gets all up and arms," the Carpet and Rug Institute's then-president told reporters at the time.

Persistent Pollution and Legal Battles

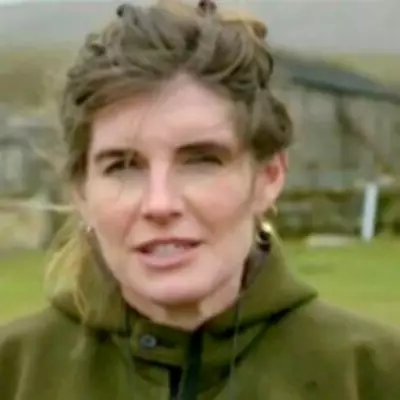

Despite claims about phasing out older PFAS formulations around 2008, contamination persists. Shaw Industries admits struggling to remove the chemicals completely from facilities, noting they appear in machines and production processes. "You can't just say you stopped using them and you're done," acknowledged Kellie Ballew, Shaw's vice president of environmental affairs.

The pollution has sparked numerous lawsuits with hundreds of millions of dollars at stake. Municipalities including Rome, Georgia, have reached settlements totaling approximately $280 million with carpet and chemical companies, though none admitted liability. Meanwhile, proposed state legislation that would have shielded carpet companies from PFAS lawsuits failed last year.

Ongoing Health Crisis

Recent testing by Emory University found three out of four northwest Georgia residents had PFAS levels warranting medical screening under clinical guidelines. "People in Rome and in Calhoun tended to have higher levels of PFAS than most of the people in the U.S. population," said Dr. Dana Barr, who led the study.

The full human toll remains unknown as contamination continues spreading. Dalton Utilities estimates cleanup costs will likely exceed hundreds of millions of dollars, with PFAS applied decades ago at treatment sites continuing to spread "for the foreseeable future."

For residents like retired Mohawk manager Lisa Martin, who discovered elevated PFAS levels in her blood, the crisis represents both a health threat and a profound betrayal. "How many people have lost their health," she asked, "because somebody made a decision not to do anything?"