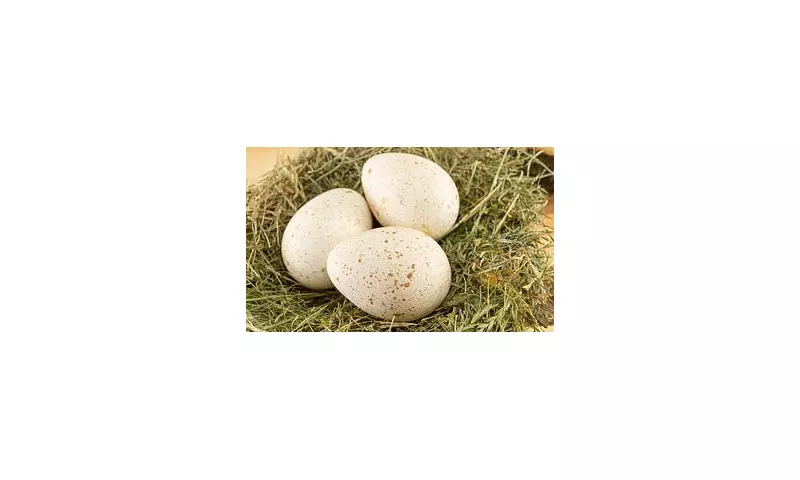

As families across the UK look forward to their festive roasts, a curious question might arise: why do we eat turkeys, but never see their eggs on the holiday menu? The answer is a complex tale of biology, economics, and history that has kept turkey eggs off our shelves.

The Economics of Egg Production

The core reason for the absence of turkey eggs boils down to simple maths and biology. Turkeys produce only one or two eggs per week, a stark contrast to chickens, which reliably lay about one egg every 24 hours. This low output is compounded by a longer growth period.

Kimmon Williams of the National Turkey Federation explained that turkeys need to reach about seven months before they can produce eggs, whereas chickens only need five months. Raising turkeys is also significantly more expensive, as they require more feed and larger housing, driving up production costs substantially.

As a result, farmers would need to charge at least $3.00 per turkey egg, making a dozen cost an eye-watering $36. This prohibitive price point makes them an impractical choice for mainstream consumption, despite some chefs noting their creamier, richer yolks are superior for sauces.

A Historical Journey of Suspicion and Luxury

Turkeys are indigenous to North America and were a staple for Native American tribes long before chickens arrived in the 1500s. When early European settlers were introduced to the birds in the 1600s, they were seen as exotic. However, their eggs were met with suspicion.

Rumours spread, largely among the French, that the eggs were linked to outbreaks of leprosy. In medieval Europe, new foods from a land deemed dangerous did not align with established norms, and diseases were often seen as divine punishment.

Despite this, in the US, the eggs were later viewed as a luxury. By the 18th century, turkey domestication was widespread, and New York's iconic Delmonico's restaurant served them scrambled, poached, and in frittatas.

The Modern Landscape and Current Challenges

The rise of industrial poultry farming in the 20th century cemented the chicken's dominance. Technological advancements allowed farmers to specialise, making chicken eggs vastly more cost-efficient and readily available. Consequently, even Delmonico's eventually removed turkey eggs from its menu.

Today, turkey eggs remain a rarity, sought mainly by food enthusiasts or farmers catering to a niche demand. The industry also faces modern threats. The American Farm Bureau Federation has warned of a possible turkey shortage after more than 600,000 birds were recently infected with Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI).

This virus has severely impacted the U.S. turkey industry, affecting roughly 18.7 million turkeys since 2022. In 2025 alone, about 2.2 million turkeys have been infected, contributing to a significant jump in wholesale prices. The US Department of Agriculture estimated the average price for a frozen whole turkey has risen by roughly 40 percent over the past year.

So, while the Christmas turkey remains a centrepiece, its eggs are destined to stay a costly and elusive delicacy, a victim of biology, history, and hard economic reality.