A renewed government push to build new towns across the UK is facing sharp criticism from the very architects of the post-war programme, who warn the current plans lack ambition on social housing and may miss those in greatest need.

Post-War Pioneers Voice Concerns

Senior figures involved in creating towns like Milton Keynes have publicly criticised the latest proposals, stating they fail to prioritise affordable council rents. Their intervention highlights a central tension: while new developments make political headlines, they historically contribute only a small fraction of the nation's housing requirement.

Instead of speculative greenfield settlements, critics argue the focus should shift to strengthening existing towns and cities. They point to the vast potential of redundant land, vacant properties, and brownfield sites within current urban boundaries. This approach, they contend, would deliver affordable, well-located homes more quickly and sustainably, while reinforcing rather than displacing established communities.

The Hollowing Out of High Streets

The debate extends beyond housing to the economic health of town centres. The letter writers note a damaging cycle where the 'gravitational pull' of out-of-town retail parks drains footfall and vitality from high streets. Each business relocation accelerates local decline, undermining the social and economic fabric. A genuine revitalisation, they argue, requires reinvestment in existing centres where people live and work, not incentives for further retail flight.

Richard Eltringham from Leicester summarised the argument, stating: "New towns may suit developers, but they will not solve the housing crisis for those who need help most."

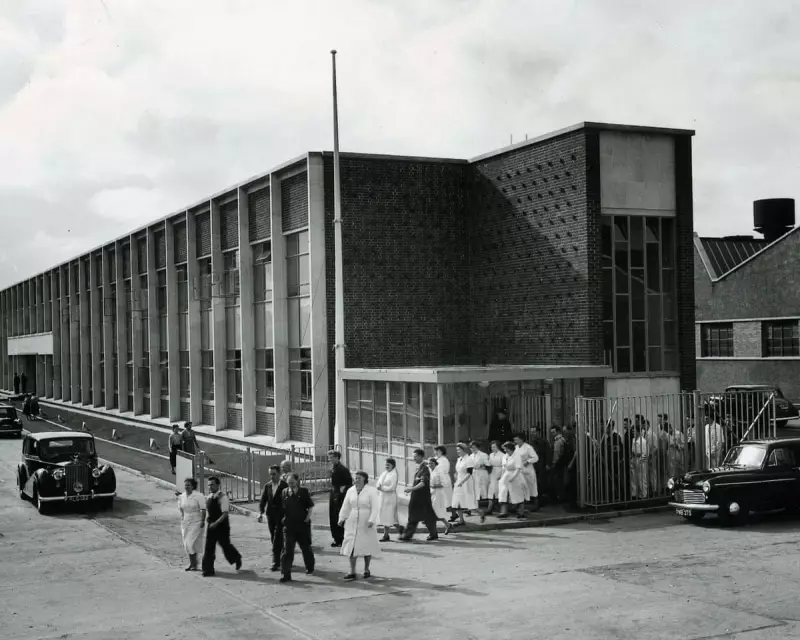

Lessons from Milton Keynes and Peterborough

Personal testimonies shed light on how the original new towns programme succeeded. Michael Edwards, an honorary professor at UCL's Bartlett School of Planning, recounted a pivotal moment in Milton Keynes' development in 1967. As the economist for the consultant team, he analysed household income data and concluded the city had to build at least half its housing for social rent to achieve its social mix goals, a stance that initially caused friction but ultimately prevailed.

Meanwhile, Les Bright recalled moving to Peterborough, a designated new town, in 1981. The Peterborough Development Corporation (PDC) offered not just a three-bedroom house, but a comprehensive masterplan encompassing jobs, cycle routes, schools, and community support. This holistic approach, funded by public and private investment, created a vibrant environment for newcomers and existing residents.

Gordon Davies, a career architect-planner who worked in Skelmersdale, East Kilbride, and Livingston, praised the historic programme as one of the UK's most significant planning successes. He attributed its impact to sustained central government support and powerful development corporations that could acquire land at existing use value. He warns that future developments must be dynamic, job-creating entities with quality public housing—not merely large-scale private housing estates.

The consensus from these experienced voices is clear: solving the housing crisis requires more than new settlements. It demands a focus on existing communities, a commitment to high levels of genuinely affordable housing, and the political will to provide long-term, strategic support.