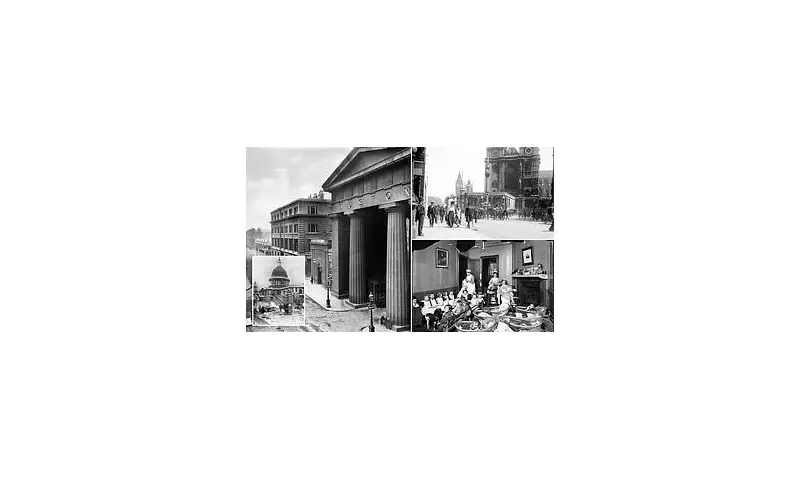

A remarkable new photographic collection has unveiled London's vanished architectural treasures, including the magnificent Euston Arch whose controversial demolition in 1962 sparked outrage among preservationists.

The Battle for Euston Arch

When demolition plans emerged for Euston Arch in 1962, prominent figures including poet Sir John Betjeman launched fierce protests to save the structure. Despite their eloquent arguments, they proved no match for Frank Valori, London's notorious 'demolition king', who proceeded to tear down the iconic gateway.

The arch, which had stood since 1837 as the original entrance to Euston Station, was designed by architect Philip Hardwick at a cost of £35,000 - equivalent to approximately £2.5 million today. Inspired by classical Roman architecture, it represented what the new book describes as 'a heroic monument to Britain's railway age'.

Panoramas of Lost London: A Visual Time Capsule

Panoramas of Lost London: Work, Wealth, Poverty and Change 1870-1945 by Philip Davies showcases not only demolished landmarks but also street scenes and Londoners from bygone eras. The collection features everything from Victorian tradesmen to Edwardian families outside their homes.

Leading architectural historian Dan Cruickshank writes in the book's foreword: 'Few photographs are more powerfully evocative than those of lost buildings of great cities.' He describes the collection as having 'astonishing emotional power and appeal', noting that while the actual buildings cannot be resurrected, the book serves as the next best thing.

Among the fascinating images are:

- The emerging skeleton of Tower Bridge during construction in 1893

- St Pancras Hotel photographed from the east in 1910

- The interior of St Pancras Station in 1895, now one of the world's busiest transport hubs

- Nurses tending children in a Deptford nursery in 1911

- St Paul's Cathedral in 1942 with bomb-damaged St Augustine's in the foreground

London's Changing Face

By 1911, London had become the largest city in the world, undergoing phenomenal expansion during the Victorian period. The metropolis was characterised by districts in constant flux, with poverty and immense wealth existing side by side.

Many significant landmarks fell victim to redevelopment schemes. The Great Hall at Euston Station, which had inspired New York's Grand Central Station, was demolished alongside the arch to make way for station redevelopment.

Other notable losses included:

- Columbia Market in Bethnal Green, demolished in 1958 for high-rise flats

- St James's Theatre, once managed by Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh

- London's Coal Exchange, described as the 'prime city monument of the early Victorian period'

- The original Army and Navy Club, Imperial Hotel, and William Blake's former Soho home

Even the Royal Albert Hall faced threats, with Valori declaring it would be 'an honour' to demolish the iconic venue.

Narrow Escapes and Controversial Plans

Not all threatened buildings met their demise. St Pancras Station narrowly avoided demolition in 1966, while ambitious plans to destroy Piccadilly Circus, Covent Garden and Thames-side landmarks were successfully opposed.

Under controversial proposals for Covent Garden, much of its south-western corner would have been replaced by concrete terracing, with only St Martin-in-the-Fields surviving. Community lobbying ultimately saved the area from this fate.

The demolition drive was partly motivated by the popularity of Brutalist architecture, which produced landmarks like the Barbican Centre, Trellick Tower and Hayward Gallery.

Most images in the new book come from the collection of the former Greater London Council Historic Buildings Division, now used regularly by Historic England for reference purposes.

Panoramas of Lost London: Work, Wealth, Poverty and Change 1870-1945 is published by Atlantic Publishing and available now, offering a poignant reminder of London's ever-evolving architectural landscape.