Veteran feminists are issuing an urgent call to preserve the living history of the groundbreaking Women's Liberation Movement (WLM) before the memories of its grassroots participants are lost forever.

A Movement, Not an Organisation

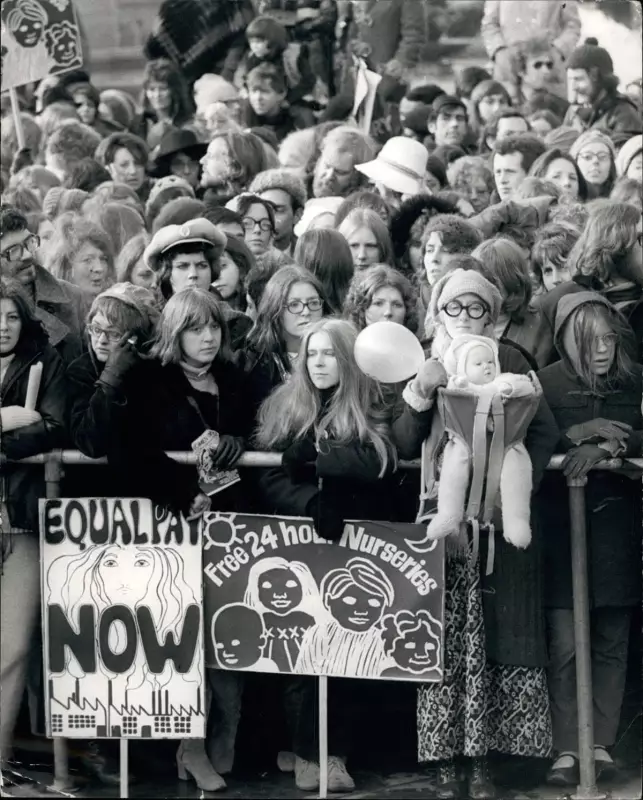

In a letter to the Guardian, long-time activists Sue O’Sullivan and Miriam David responded to a recent article on the Sex Discrimination Act. They emphasise that the WLM, which saw iconic marches like the one from Hyde Park to Trafalgar Square on 6 March 1971, was a fluid political force, not a formal body. They clarify that there were no membership forms, and the national conferences served more as large-scale "consciousness-raising" events than structured meetings.

"The most important 'votes' were often about adding demands to our growing list," they write, highlighting the often volatile debates that shaped the movement's evolving goals. They express concern that the intricate struggles between those fighting for legal equal rights and those advocating more radical change are rapidly fading from direct lived experience.

The 'Howl' Project: Capturing Voices in Time

To combat this historical erosion, O’Sullivan and David reveal they are part of a voluntary group called Howl (History of Women’s Liberation). This initiative is actively working to record the testimonies of those involved at all levels. "For an inclusive history’s sake, it’s time to record as many of those voices, including grassroots ones, before it’s too late," they state.

The project is now online, already amassing a significant archive of personal stories, photographs, illustrations, and resource material. Their rallying cry is simple: "We want more!" They encourage anyone with memories or memorabilia from the era to come forward and contribute to this vital historical record.

Forgotten Pioneers: The Wartime Roots of Equality

A separate letter from Paul F Faupel adds a crucial, earlier chapter to the narrative of Britain's fight against sex discrimination. He points to the wartime Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA), led by Pauline Gower, as a pioneering force for workplace equality.

Faupel notes that Gower instituted equal pay for male and female pilots and merit-based opportunity within the ATA, a stark contrast to the misogyny female aviators faced pre-war. He cites Becky Aikman's book, "Spitfires – The American Women Who Flew In The Face Of Danger During World War II," which details how this experience highlighted the need to eliminate sex discrimination.

Despite this progress, Faupel laments that postwar opportunities in both the UK and US were stifled by returning male pilots and persistent discrimination. Pauline Gower's early death in 1947, aged 36, left a void in the ongoing push for equality, prompting reflection on what more she might have achieved.

Together, these letters underscore a continuous, multi-generational struggle for gender equality in Britain. They highlight the pressing need to document its complex history from the pioneering efforts of the 1940s to the radical street movements of the 1970s, ensuring future generations understand the depth and breadth of the fight.