A major new $2bn (£1.5bn) humanitarian aid pledge from the United States has been met with deep concern by experts, who warn it forces the United Nations into a corner and prioritises Washington's political interests over global need.

A Pledge Laden with Political Demands

Announced this week, the funding was described as "bold and ambitious" by UN officials. However, the pledge came with stringent conditions that have sparked alarm. The US State Department explicitly stated the UN must "adapt, shrink or die" by cutting waste and implementing reforms. Furthermore, the money must be channelled through a single pooled fund under the UN's Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (Ocha), rather than going directly to individual agencies.

Perhaps most controversially, the US has stipulated that the aid can only be used in 17 priority countries of its choosing. This list excludes nations experiencing profound humanitarian catastrophes, notably Afghanistan and Yemen.

Experts Decry 'Subservience' and a Shrinking System

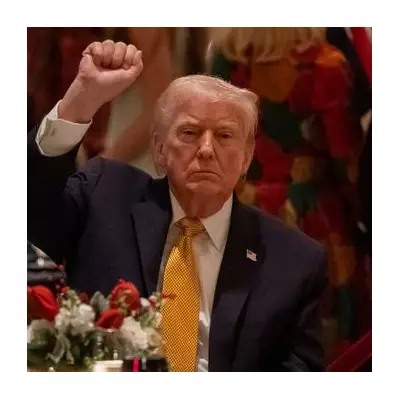

Themrise Khan, an independent aid systems researcher, condemned the approach. "It's a despicable way of looking at humanitarianism and humanitarian aid," she said. Khan criticised the UN for praising the Trump administration's "generosity" despite the onerous terms.

"It also points to the fact that the UN system itself is now so subservient to the American system – that it is literally bowing down to just one power," Khan added. "For me, that is the nail in the coffin."

The 17 countries include several where the US has clear political stakes, such as Sudan, Haiti, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and several Latin American nations. Ronny Patz, an analyst specialising in UN finances, noted that pre-selecting countries "shows they have very clear political priorities for this money."

Patz warned the demands risk "solidifying a massively shrunk UN humanitarian system" that may be unable to respond flexibly to new crises outside the US list next year.

Is the $2bn Pledge All It Seems?

Beyond the conditions, analysts question whether the pledged amount represents genuine progress. Thomas Byrnes of MarketImpact consultancy noted the $2bn is significantly less than the $3.38bn the US provided to the UN in 2025 under the previous Biden administration.

"This is a carefully staged political announcement that obscures more than it reveals," Byrnes stated. He contextualised the pledge against other US moves, including cutting $5bn in already-approved foreign aid labelled "woke, weaponised and wasteful," and a proposal to end support for peacekeeping missions.

Both Byrnes and Patz raised concerns that channelling funds through Ocha may be less about partnership and more about centralising control. Patz also expressed scepticism about the money materialising at all if the UN fails to meet US Secretary of State Marco Rubio's demands to "cut bloat, remove duplication."

"I would be cautious," Patz concluded. "This is $2bn promised, but not $2bn given." The announcement, following a year of deep aid cuts from the US and European nations, offers limited relief while casting a long shadow over the future of independent, needs-based humanitarian action.