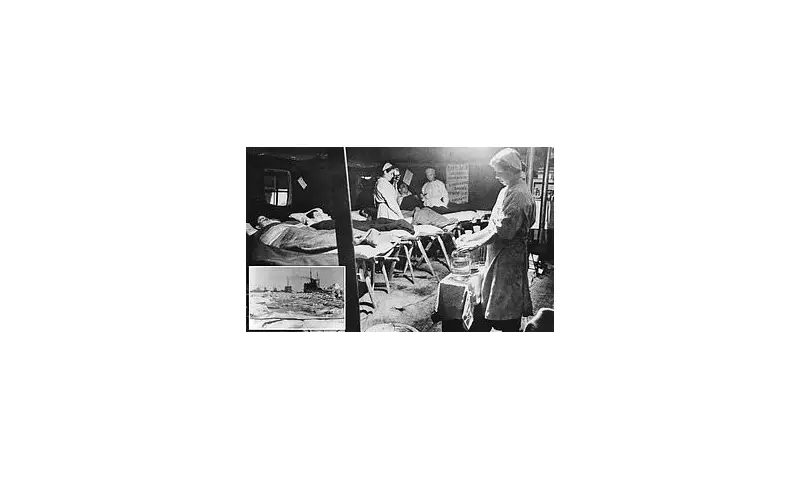

The piercing screams of the wounded, the nauseating stench of infected flesh, and the grim rasp of a bone saw: these were the sounds and smells that greeted injured Allied sailors delivered to Soviet field hospitals during the Second World War's perilous Arctic convoys.

A Journey into a Medical Nightmare

From August 1941 to May 1945, Allied merchant seamen, including British, Dutch, Norwegian, American, and Polish personnel, braved what Winston Churchill termed 'the worst journey in the world'. Their mission was to shepherd vital weapons, food, and supplies from Iceland to Russia's northern ports, running a gauntlet of German bombers, U-boats, and freezing temperatures as low as minus 18°C. For the 2,773 who perished, the sea was their grave. For the wounded who reached land, a different kind of hell awaited in hospitals like the one in Murmansk.

Morris Mills, an 18-year-old British seaman, captured the horror in his memoirs. His ship, the SS New Westminster City, part of convoy PQ13, limped into Murmansk in April 1942 after a ferocious attack by 20 German bombers. Mills suffered a catastrophic injury. 'I saw my left foot had been smashed to a bloody pulp and was only connected to my leg by strips of sinew,' he wrote. Awakening in the Soviet hospital, he witnessed an amputation that would haunt him: 'The harsh rasp of the saw... invoked a visceral stabbing pain to shoot through my own stump.'

'Medieval' Care and a Pistol-Wielding Doctor

The medical practices encountered by the Allied sailors were described by British naval surgeons as 'bloody awful' and 'medieval'. Lieutenant John Ballantyne, the acting Base Medical Officer, filed a damning report, stating Russian doctors 'seem to lack the very fundamentals of medical and surgical practice.' Amputations for gangrene were common, often performed with little or no anaesthetic. Engineer Officer Bill Short recalled the blunt diagnosis for his frostbitten, gangrenous legs: 'Someone said in broken English, "We're going to take your legs off."' He remembered only 'an excruciating pain' before passing out.

The ordeal did not end with surgery. Dressings made of a stiff, paper-like material were agonisingly removed from raw stumps, a procedure Mills said required three nurses: one to hold the patient down, one to grip the stump, and one to pick at the wound. The environment was fraught with danger. Mills described a moment when a nurse touched a nerve, causing his leg to jerk violently and knock over a trolley. 'The army doctor came rushing over... withdrew an enormous pistol, pointing it with a trembling hand straight between my eyes,' he wrote, before the doctor stormed out.

Other treatments baffled and pained the British contingent. Nurses administered enemas and pushed rubber tubes down throats to defrost stomachs with tepid water. They used jars of burning hot goose grease placed on patients' chests to 'heat the inner organs'. The food was 'nauseating', the sanitary conditions primitive, and the stench of sepsis overwhelming.

Resilience Amidst the Ruins

Despite the dire conditions, remarkable stories of resilience emerged. A Portuguese seaman, Carlos Luz, had both hands and legs amputated. Fellow patient Bill Short described him as 'an inspiration to us all', noting he would walk around on his knees and play the harmonica to entertain the ward. Yet another sailor heard his 'broken-hearted sobbing' at night.

As the immediate crisis passed, a semblance of normalcy and dark humour returned. Jokes about the poor food were common. When meat was on the menu, someone would quip: 'Someone is going to have an amputation today.' For 15-year-old cabin boy Jimmy Campbell, who lost a leg and parts of both hands, a moment of unexpected levity came when a group of naked female Red Army anti-aircraft gunners surrounded him in the bath, sending the young sailor into a state of shock and embarrassment.

The hospital itself was a frequent target of German bombing raids, causing terrified, limbless patients to dive under their beds, often re-injuring themselves. Mills recalled being abandoned by staff during raids, left to listen as a mortally wounded Polish seaman took 'an incredibly long time to die' on the floor, with no one coming to help.

The crusade to improve these conditions was notably taken up by Lady (Juliet) Duff, a friend of Churchill's wife, who lobbied tirelessly back in England. The survivors' testimonies, now held in archives like the National Archives in Maryland, USA, stand as a stark testament to a hidden chapter of Allied sacrifice—one where deliverance to port was just the beginning of a fight for survival against infection, crude medicine, and indifference.