Eighty years ago, as the United States dropped an atomic bomb on Nagasaki, a little-known group of victims endured the blast: hundreds of Allied prisoners of war held in brutal Japanese camps within the city. Their harrowing experiences, often overlooked in the broader narrative of the war's end, are now being brought to light through the determined efforts of families and researchers.

The Camps and the Captives

Nearly 1,500 POWs were held at the Fukuoka No. 2 Branch Camp, forced into slave labour at the Kawanami shipyard. Many were Dutch servicemen captured in Indonesia and transported to Japan on notorious "hell ships." They were housed at two major camps in Nagasaki: Fukuoka No. 2 and Fukuoka No. 14.

According to the POW Research Network Japan, about 150,000 Allied prisoners were held across Asia during the conflict. Of these, 36,000 were sent to Japan to address wartime labour shortages. Alongside the Dutch, prisoners from the United States, Britain, and Australia were also present in Nagasaki. While none at the No. 2 Camp died in the atomic blast, over 70 had already perished from malnutrition, overwork, and illness.

Personal Testimonies of Survival and Loss

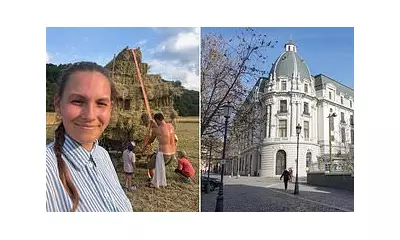

Andre Schram, son of Dutch sailor Johan Willem Schram, represented families at a Nagasaki memorial unveiled in 2015. His father, like many others, only spoke of being treated "like a slave" near the end of his life. Despite official Japanese apologies, Johan doubted their sincerity and felt disrespected by both Japan and the Netherlands, never wishing to engage with Japan again.

Another Dutch POW's son, Peter Klok, recounted his father Leendert's complex experience. While some Japanese civilians at the shipyard kindly helped him repair his watch, military police later beat him for seeking that assistance. Klok believed the atomic bombings were awful but insisted Japan must reflect on its own atrocities.

The bombing on 9 August 1945 was witnessed by prisoners. British captive Tom Humphrey, at Camp No. 2 about 10 kilometres from ground zero, described a huge orange fireball, purple smoke, and a triple-layer mushroom cloud in his diary. The blast shattered windows and blew doors off their hinges.

Fukuoka Camp No. 14 was much closer to the epicentre. Its brick buildings were destroyed, killing eight POWs and injuring dozens. Dutch survivor Rene Schafer recalled jumping into a bunker; his roommate suffered severe burns and died nine days later. Australian Peter McGrath-Kerr was dug out from debris, unconscious for five days with broken ribs, cuts, and radiation burns.

Reckoning with a Painful Legacy

In the aftermath, prisoners from the less-damaged No. 2 Camp provided rice and aid to their comrades from No. 14. They were notified of Japan's surrender on 18 August, received their first Allied food drop on 26 August, and left Nagasaki for the Philippines on 13 September.

Decades later, reconciliation efforts continue. In September 2025, dozens of relatives of Dutch POWs and descendants of Japanese survivors gathered in Nagasaki for a joint commemoration. This followed independent research by individuals like Japanese survivor Shigeaki Mori in Hiroshima, whose work led the US to confirm the deaths of 12 American POWs in that city's bombing—an act recognised by former President Barack Obama in 2016.

The POW Research Network notes that at least 11 former POWs from Nagasaki—seven Dutch, three Australian, and one British—received official atomic bombing survivor certificates. Taeko Sasamoto, the network's co-founder, states this history has been "swept under the rug," requiring painstaking examination of documents that have attracted little academic interest. "It's an important issue that has long been neglected," she said.