A surprising beauty and wellness trend from the 1920s is capturing fresh attention. In December 1925, newspapers reported a significant revival in the practice of taking mud baths, hailed both as a powerful beauty treatment and a curative remedy for various physical ailments.

The Therapeutic Power of Peat

Far from a simple fad, these specialised mud baths were considered highly effective for specific health complaints. Medical conditions such as rheumatism, sciatica, lumbago, and gout were primary targets for the treatment. Even for those without these issues, advocates promoted the baths for their profound tonic effect on the entire body and their unparalleled ability to ensure skin clarity. This dual benefit made the practice increasingly popular with women dedicated to the most effective beauty regimes of the era.

Interestingly, the 'mud' used by beauty experts was actually peat. A substantial portion of this peat originated from the area around Goole in Yorkshire. Demand was so high that many tons were dispatched weekly to treatment centres across the country.

An Acquired Art: How to Take a Mud Bath

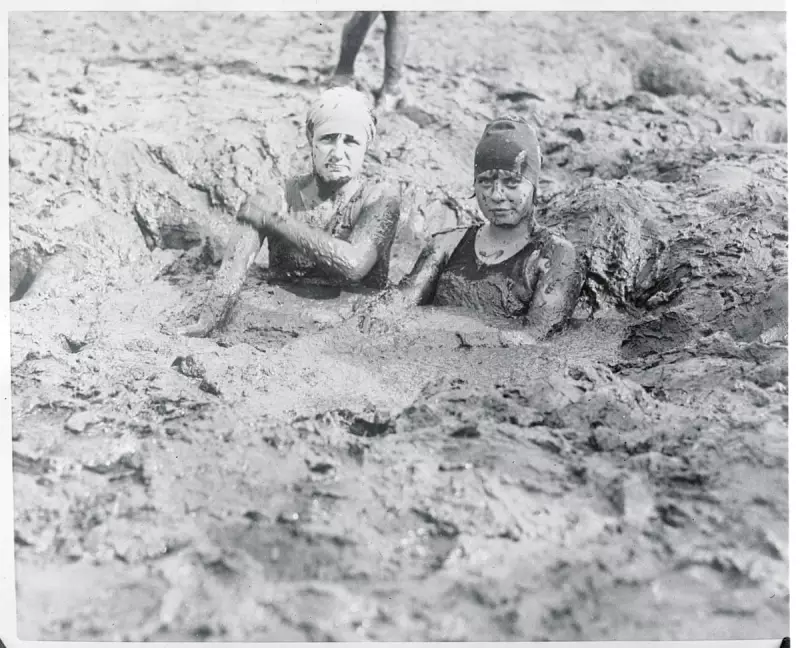

Undergoing a mud bath was described as an acquired art, with a specific technique required. Bathers were instructed to step gently into the peat mixture and carefully lower their bodies until only the head remained above the surface. They would then remain immersed for a strict duration of 20 minutes.

Contrary to what one might imagine, reports from the time insisted the experience was not unpleasant. The muddy mixture provided a warm, enveloping sensation. After the allotted time, the bather would scramble out, leaving most of the mud behind, before proceeding to a warm shower to wash off the remaining peaty paste. The process concluded with the individual wrapped in heated towels, feeling rejuvenated, and resting on a couch.

From Skepticism to Widespread Popularity

Novices, or those new to 'mud wallowing', were often filled with qualms. Assurances about the specially prepared peat—rich in organic acids and containing iron—did little to immediately calm fears. However, firsthand experience of its purported benefits reportedly turned skeptics into enthusiasts.

The scale of the trend's popularity was evident at Harrogate, which boasted the largest installation of peat baths in Europe. During the season, the facility used approximately 25 tons of specially selected peat each week to meet demand.

While enjoying a renaissance in the 1920s, the mud bath was not a new invention. Historical records noted its popularity some 150 years prior, recommended then as an excellent preservative for beauties. One famous adherent was Emma, Lady Hamilton, the renowned beauty and muse of Lord Nelson. Her belief was so strong that she once publicly sat immersed in a peat bath up to her neck to promote the methods of a contemporary 'doctor' championing the treatment.

Although the medical establishment of that earlier era dismissed the idea, by 1925, doctors had begun to recognise the skin-clarifying effects of the peat bath and acknowledged its benefits for sufferers of diseases linked to uric acid.