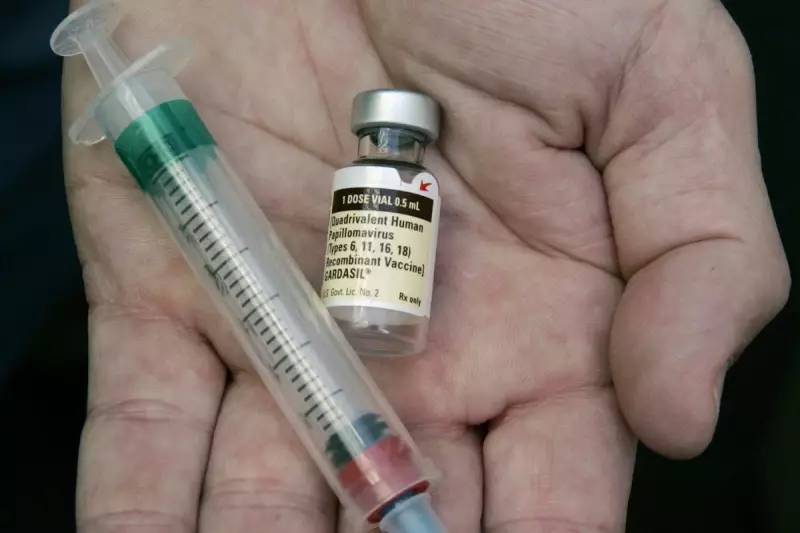

A major new study has delivered potentially game-changing news for global public health, indicating that a single dose of the HPV vaccine could be just as effective as the standard two-dose regimen in preventing the viral infection that causes cervical cancer.

Groundbreaking Findings from Costa Rica

Researchers from the U.S. National Cancer Institute and Costa Rica's Agency for Biomedical Research reported their findings on Wednesday 3 December 2025. The extensive study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, enrolled more than 20,000 girls aged between 12 and 16 in Costa Rica.

The participants were split into groups receiving one of two different HPV vaccines used globally. Six months later, half received a second dose of their assigned vaccine, while the other half were given an unrelated childhood vaccination instead. All participants were then monitored for a period of five years with regular cervical screening for the most cancer-prone strains of HPV.

Striking Efficacy of a Single Shot

The results were striking. The research concluded that a single HPV shot provided approximately 97% protection against the targeted viral infections. This level of efficacy was found to be similar to that offered by two doses when compared against a separate, unvaccinated control group.

While previous research had hinted at the potential of a one-dose schedule, this study provides robust confirmation of strong protection lasting for at least five years. Human papillomavirus (HPV) is a very common sexually transmitted infection. While most cases clear independently, persistent infections can lead to various cancers years later, most notably cervical cancer in women.

Implications for Global Health Policy

This discovery holds profound significance for worldwide immunisation campaigns, particularly in low-income and harder-to-reach regions. Cervical cancer remains a leading cause of death, claiming an estimated 340,000 women's lives globally each year. Simplifying the vaccination protocol from two doses to one could dramatically increase uptake and logistical feasibility.

Dr. Ruanne Barnabas of Massachusetts General Hospital, who was not involved in the study, highlighted the importance of the findings in an accompanying editorial. "We have the evidence and tools to eliminate cervical cancer. What remains is the collective will to implement them equitably, effectively, and now," she wrote.

In the United Kingdom and the United States, health authorities currently recommend two doses of the HPV vaccine, typically starting at age 11 or 12. The CDC reports that about 78% of U.S. adolescents have received at least one dose. Globally, however, the World Health Organization estimates less than a third of adolescent girls are vaccinated. The WHO had already begun recommending one or two doses to broaden protection.

Researchers caution that longer-term monitoring is still needed, and the study did not provide data on HPV-related cancers beyond the cervix, such as head-and-neck cancers. Nevertheless, the evidence presents a powerful opportunity to accelerate the fight against a preventable disease.