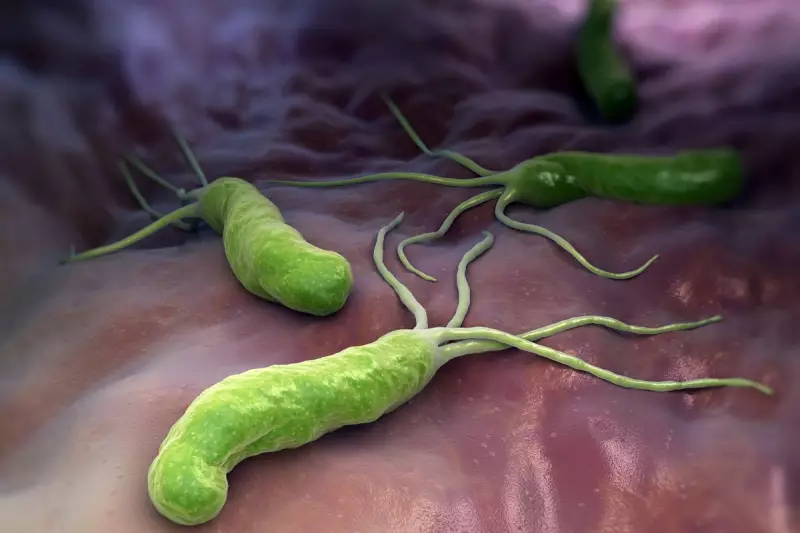

In a surprising scientific twist, a bacterium infamous for causing stomach ulcers may point the way to a novel defence against Alzheimer's disease. New research indicates that a protein fragment from Helicobacter pylori can effectively block the toxic accumulation of the key proteins believed to drive the neurodegenerative condition.

From Stomach Bug to Brain Shield

The study, led by Associate Professor Gefei Chen at the Karolinska Institutet and published on Saturday 6 December 2025, began with an investigation into bacterial behaviour. The team was exploring how H. pylori interacts with other microbes, particularly within protective communities called biofilms. These biofilms often use amyloid assemblies—structurally similar to the plaques found in Alzheimer's-affected brains—as a scaffold.

This connection prompted a critical question: could H. pylori influence these amyloid structures in humans? The researchers focused on a known protein from the bacterium called CagA. While one half of this protein is harmful, the other half, known as the N-terminal fragment or CagAN, showed unexpected promise.

In initial tests, the CagAN fragment dramatically reduced the formation of bacterial amyloids and biofilms. Encouraged, the team then applied it to human amyloid-beta proteins in a laboratory setting.

Blocking the Hallmarks of Alzheimer's

The results were striking. When amyloid-beta molecules were incubated with the CagAN fragment, the formation of sticky amyloid clumps was significantly reduced. Using fluorescence readers and electron microscopes, scientists observed that even at low concentrations, CagAN almost completely halted amyloid aggregation.

Further investigation using nuclear magnetic resonance and computer modelling revealed how the fragment interacts with amyloid-beta. Remarkably, the same bacterial protein also blocked the aggregation of tau protein, which forms destructive tangles inside brain cells. This dual action against both hallmark proteins of Alzheimer's disease—amyloid plaques and tau tangles—marks a significant departure from existing treatments that target only one.

Current monoclonal antibody drugs, approved in recent years, aim to clear amyloid-beta but are only effective in early stages, do not reverse damage, and can cause serious side effects like brain swelling.

Potential for Broher Therapeutic Impact

The implications of this discovery may extend far beyond Alzheimer's disease. In additional experiments, the CagAN fragment also blocked the aggregation of proteins linked to other conditions: IAPP in type 2 diabetes and alpha-synuclein in Parkinson's disease.

This suggests that these diverse diseases, which affect different parts of the body, may share a common mechanism of toxic protein accumulation that the bacterial fragment can disrupt. The finding opens the door to the possibility of developing drugs modelled on this bacterial protein to block the earliest molecular signs of several major diseases.

However, the researchers urge caution. All experiments have so far been conducted in laboratory settings, not yet in animal or human models. The study is at an early stage, but it uncovers a compelling new path for research.

The discovery also adds a complex layer to our understanding of H. pylori. Long viewed solely as a harmful pathogen, this research suggests parts of it might have protective properties. It prompts a future where medicine might adopt a more precise approach, not aiming to eradicate every microbe but to understand and potentially harness specific beneficial components.

As Professor Chen notes, the future of treatment may involve a more personalised strategy, distinguishing between the harmful and helpful parts of bacteria like H. pylori in our ongoing fight against neurodegenerative diseases.