A fresh scientific investigation into a set of 7-million-year-old bones has reignited a fierce debate about the identity of humanity's earliest possible ancestor. Researchers argue that an ape-like species, Sahelanthropus tchadensis, shows crucial signs of walking upright, potentially making it the oldest known member of the human lineage.

The Fossil at the Heart of the Feud

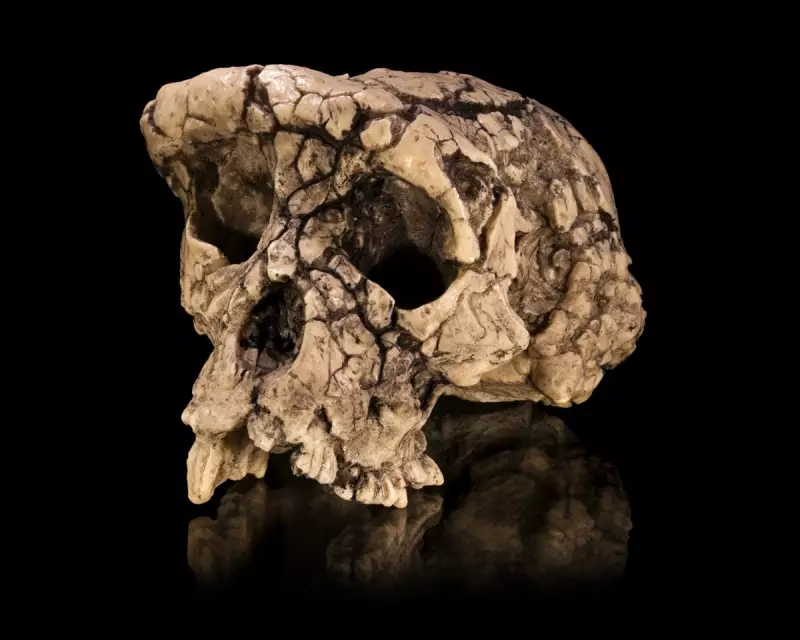

The controversy began in 2001 when a team led by Professor Michel Brunet from the University of Poitiers in France discovered fossils in the Djurab desert of Chad. The find included a skull, nicknamed Toumaï, and later, a partial thigh bone and forearm bones. Brunet's team suggested the creature's skull placement indicated it walked on two legs, boldly declaring it "the ancestor of all humankind."

However, with so few bones available, particularly from the lower body, many scientists remained sceptical. The debate has simmered for over two decades, with experts divided on whether Sahelanthropus was a bipedal hominin or an ancient ape related to chimpanzees.

New Analysis Points to Upright Walking

In the latest study, published in Science Advances, a team led by Dr Scott Williams of New York University re-examined the thigh and forearm bones using modern techniques. They compared the fossils' 3D contours, size, and proportions to those of known hominins and apes.

The researchers identified several features they believe are hallmarks of bipedalism. A key piece of evidence is a small bump on the thigh bone, known as the femoral tubercle. "It's the attachment point for the largest and most powerful ligament in our bodies," explained Dr Williams. "It's a really important adaptation for bipedal walking and, as far as I know, has only been identified in bipedal hominins."

Other indicators included a natural twist in the thigh bone that helps the leg point forward and evidence of buttock muscles that stabilise the hips during standing and walking. "We think the earliest hominins were adapting to terrestrial bipedalism," Williams said, "but were still relying on trees for foraging and seeking safety."

Scientific Skepticism and the Call for More Fossils

Despite the new claims, significant doubts persist within the palaeontology community. Dr Marine Cazenave of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology described the evidence for upright walking as "weak," noting that most features resembled those of African great apes. She also questioned the femoral tubercle, pointing out it was in a damaged area of the bone.

Dr Rhianna Drummond-Clarke, from the same institute, found some evidence convincing but raised an alternative possibility. The results could suggest Sahelanthropus was an early chimpanzee ancestor that became less upright over time, evolving into a knuckle-walker.

This polarised view highlights the central problem: a lack of conclusive evidence. As Dr Williams himself noted, "I think it's a case of too few fossils and too many researchers." Colleagues in France, including Dr Guillaume Daver and Dr Franck Guy, who support the bipedalism theory, agree that only more fossils will settle the debate. They hope new discoveries will be made when the Chadian-French team returns to the excavation site later this year.

The story of Sahelanthropus tchadensis remains a compelling, unresolved chapter in the epic tale of human evolution. Whether it stands as our oldest upright-walking ancestor or an intriguing evolutionary cousin, its bones continue to challenge and inspire scientists in the quest to understand our own origins.