Thirteen ambulances sit in a line behind the Emergency Department at Royal Stoke University Hospital, their blue lights silent. Inside each vehicle, a patient waits, some for over four hours, to even cross the threshold into the overstretched A&E. This scene, captured on a recent Tuesday afternoon, is a stark illustration of the immense pressure facing Britain's National Health Service this winter.

A System Under Unprecedented Strain

Deputy medical director Ann-Marie Morris surveys the gridlock with a weary professionalism. The reason for the queue is simple: there are no beds inside. The hospital's 1,178 official beds are all occupied, with an additional 15 patients being treated in ED corridors and 20 more in similar situations on other wards. The trust's Operational Pressure Escalation Level (Opel) is at 4, the highest alert before declaring a critical incident where it cannot guarantee safe delivery of all services.

This perfect storm combines an early and severe surge in flu cases with a five-day strike by junior doctors, leading to warnings from health leaders of a potential "armageddon" and a "flu-nami". Yet for the staff at this Staffordshire regional hub, it feels like an intensification of a never-ending "permacrisis". Dan Hobby, matron for general surgery, notes that the extreme pressure now feels perennial: "It almost feels like winter is 12 months a year. We are permanently in winter."

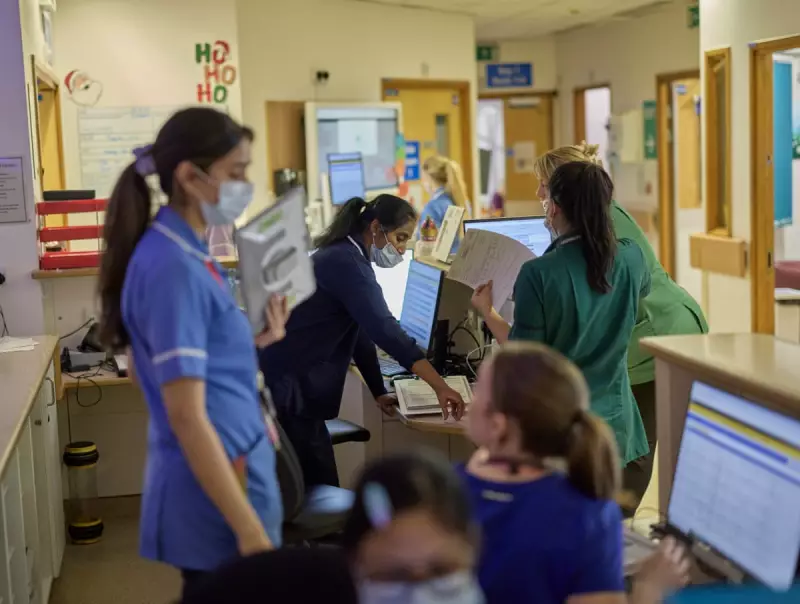

Inside the Battle for Every Bed

The Guardian was granted rare access to witness the intricate, hourly logistical battle to move patients through the system. On a respiratory ward adorned with tinsel, consultant Dr Ashwin Rajhan faces a typical dilemma. The ward, with a capacity for 20 non-invasive ventilation (NIV) patients, already had 21. Yet four more patients in A&E needed NIV beds.

The solution involved urgent physiotherapy assessments to prepare existing patients for discharge, a process hampered by broken computers. "One of the discharge facilitators has physically gone down to another part of the building, dragged the IT person up," Dr Rajhan explained. Every bed cleared creates a ripple effect: freeing a space in A&E, which then empties an ambulance, allowing paramedics to collect another critically ill person.

Elsewhere, the strain is equally palpable. On the critical care ward, patient Tracey Wootton has been waiting three days for a transfer to a general medical ward, far exceeding the four-hour national standard. The Surgical Assessment Unit, designed for 30 patients on loungers, currently holds 55, forcing some onto plastic chairs.

Navigating Strikes and a Surge in Flu

The junior doctors' strike, the 14th in the long-running dispute, adds another layer of complexity. While senior staff remain sanguine, others foresee a "massive" impact on discharges, as consultants may not be as familiar with the computer systems needed to process them. Dr Rajhan acknowledges a "learning curve" but finds workarounds, like direct phone calls to colleagues.

The early flu surge presents a particular danger to vulnerable patients like 74-year-old Raymond Dutton, a former police officer with motor neurone disease. Isolating infectious patients is a priority, putting side rooms at a premium. While flu cases have plateaued locally after a critical incident was declared on 6 December, fears remain of a second wave post-Christmas.

In a windowless operations room, clinical head of operations Becky Ferneyhough and her team monitor live data on patient flow. The numbers tell a stressful story: 12 ambulances waiting at 8:30 am, eight by lunchtime, and 20 by 5 pm. "The patient is the most important part of everything that we do," Ferneyhough emphasises, highlighting the difficult balance between caring for current patients and those waiting at home to come in.

Through admission avoidance schemes, 'virtual wards', and sheer ingenuity, staff fight to keep the system moving. Yet the underlying reality of institutional gridlock remains. As one senior nurse quietly admits, the brutal reality of corridor care is often considered "too distressing to expose". At Royal Stoke, and across the NHS, the winter crisis is not a coming event—it is the exhausting, everyday reality.