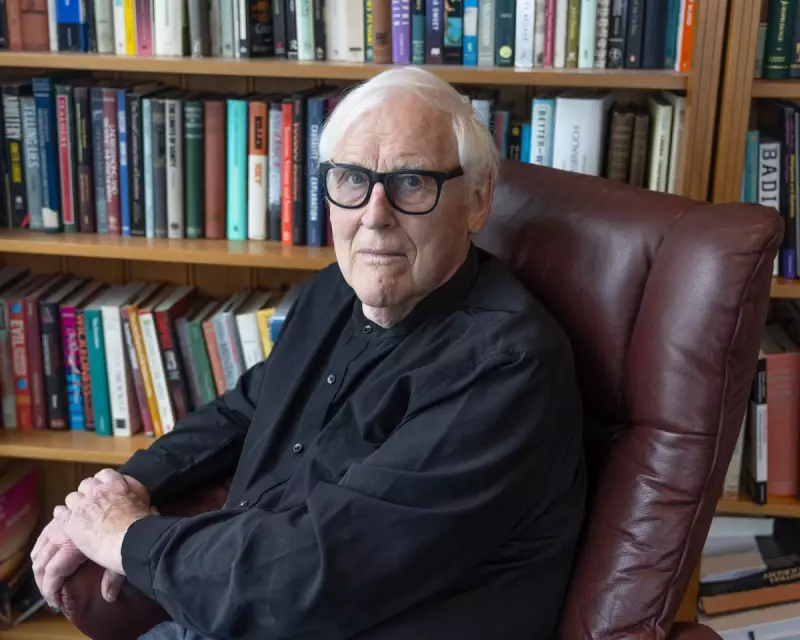

The Psychiatrist Who Spent Decades Studying Lone Mass Killers

Dr Paul E Mullen, a distinguished forensic psychiatrist, has dedicated over three decades to understanding one of society's most disturbing phenomena: the lone mass killer. From his front-row seat to some of the worst public massacres in recent history, including Port Arthur and Hoddle Street, the 81-year-old expert has developed crucial insights into what drives these individuals and, most importantly, how we might prevent such tragedies.

From Aramoana to Port Arthur: A Career Forged in Tragedy

The Bristol-born psychiatrist's journey into this dark field began unexpectedly in November 1990 while living near Dunedin, New Zealand. One evening, he and his family heard sustained gunfire followed by emergency vehicles. A hospital colleague soon revealed the horrifying truth: a gunman had begun shooting in the nearby settlement of Aramoana.

"I'd never really thought about these things," Dr Mullen tells the Guardian. "They had never been on my radar." The tragedy personally affected him as he discovered many victims were people he knew through his work.

This experience transformed his career trajectory. Though he had always dabbled in forensic work, the Aramoana massacre compelled him to pivot completely to forensic psychiatry, specialising in gravest acts from stalking and child sexual abuse to mass killings.

His most significant encounter came just six years later during the Port Arthur massacre in Tasmania. By then working as professor of forensic psychiatry at Monash University, he received an urgent call summoning him to Royal Hobart hospital where the perpetrator had been taken alive after shooting 55 people and killing 35.

"That was my first experience of actually spending time with one of these killers and beginning to find out something about them," Dr Mullen recalls.

Understanding the Cultural Script Behind Mass Killings

Dr Mullen's approach differs dramatically from public perception. While media described the Port Arthur killer in terms like "evil" and "monster," he approached the restrained 28-year-old not as a "killer" but as a "person who has killed," seeking to build rapport.

During their conversation, a revealing moment occurred when the young man suddenly asked: "I've got the record, haven't I?" This demonstrated his awareness of previous massacres, a pattern Dr Mullen would encounter repeatedly.

Through decades of research, Dr Mullen identified what he calls a "cultural script" that has developed around mass killings. He traces this phenomenon back to 1913 Germany, when a schoolteacher killed his family before indiscriminately shooting nine people in Mühlhausen.

However, the modern script truly began with the 1966 University of Texas tower shooting, where a 25-year-old student killed 15 people from a 28th-floor observation deck. "He was in every major newspaper in America, on the front page the next day with his photograph and his name," Dr Mullen explains. "It was the Texas university tower massacre that created the script, which has now grown and grown."

The first imitator appeared just five weeks later, establishing a pattern that continues today. These perpetrators often feel friendless and weak, accumulating grievances until resentment becomes their entire worldview. "The resentment builds up and builds up," Dr Mullen says, "and it becomes your whole attitude to the world, which is angry, which is full of a sense of grievance."

Disrupting the Script: Practical Prevention Strategies

In his new book, Running Amok: Inside the Mind of the Lone Mass Killer, Dr Mullen presents concrete strategies for reducing such violence. He deliberately avoids naming modern perpetrators, instead focusing on victims' names and lives.

Refusing to name killers is the "quickest, cheapest and easiest way we can cut down this escalating rate of killings," he asserts. He also warns against using terms like "lone wolf," explaining: "This is exactly what they want to be seen as – the lone wolf, the predator going around the edges. They're not wolves. I mean, they're sheep."

Other prevention methods include capturing perpetrators alive when possible, avoiding detailed reporting of their lives and manifestos, and preventing them from using courtrooms as platforms. Dr Mullen acknowledges the challenge of balancing public safety with due process and a free press, particularly in today's attention-driven media landscape.

Interestingly, Dr Mullen initially struggled to find a publisher for his nuanced approach. Some rejected him for lacking a "profile," which he attributes to deliberately maintaining anonymity due to death threats received throughout his career.

His research reveals that these crimes represent not "shameful, utterly wicked criminality" but predictable patterns that can be interrupted. "These people are uncertain whether they're going to do it up to the last moments," he notes. "One tossed a coin. The Tasmanian killer stopped at a cafe because his biggest grievance was that no one would ever talk to him."

Despite facing individuals who have committed unthinkable acts, Dr Mullen maintains his professional curiosity. "I mean, they're people. My job is to understand why they've done something extraordinary. Understanding doesn't mean forgiving. Understanding doesn't mean it's OK."

His work offers hope that by recognising and disrupting these cultural scripts, we might save potential victims – and possibly even the perpetrators themselves from their tragic destinies.