The slow, steady disappearance of the printed newspaper from doorsteps and newsstands is altering far more than just how people consume information. It is changing the very fabric of daily life, community rituals, and even the practical workflows of households and organisations across the globe.

More Than Just News: The Physical Object's Many Roles

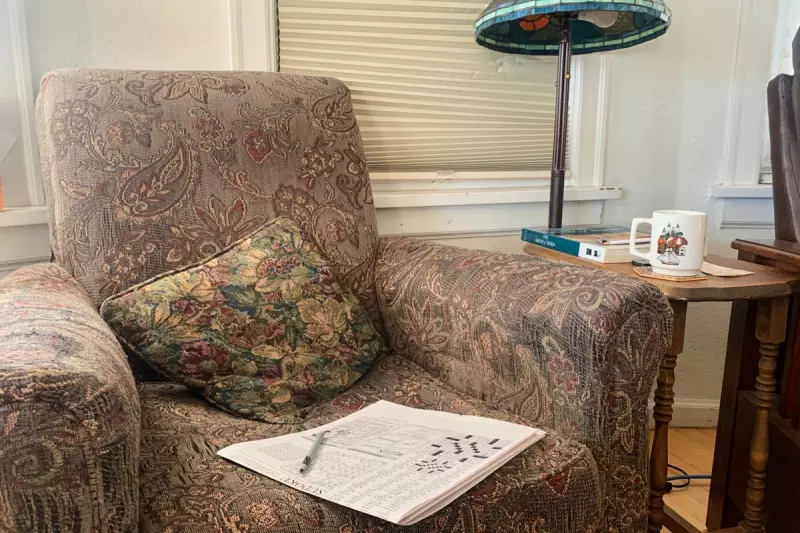

For generations, the newspaper served a dual purpose. It was first a source of information, then a versatile household tool. Robin Gammons from Montana recalls racing for the Montana Standard before school, seeking comics while her father wanted sports. The paper validated family achievements, with honour roll mentions or gallery show reviews ending up proudly displayed on the refrigerator for years.

This secondary life for newsprint was remarkably varied. Diane DeBlois, a founder of the Ephemera Society of America, lists some common historical uses: "Newspapers wrapped fish. They washed windows. They appeared in outhouses. And — free toilet paper." Beyond these, people used them to line pet cages, protect floors during DIY projects, wrap gifts, and kindle fires.

The Practical Cost of a Digital Shift

The economic pressures on print are stark. The Montana Standard cut its print circulation to three days a week two years ago, joining over 1,200 U.S. newspapers that have reduced printing frequency in the past two decades. Approximately 3,500 papers have closed entirely in that time, a rate of about two per week this year.

This decline has tangible consequences for institutions that relied on donated papers. Laura Stastny, Executive Director of Nebraska Wildlife Rehab, states they use newspaper for most of the over 8,000 animals they care for annually. Losing this free resource could cost the centre more than $10,000 a year for alternatives.

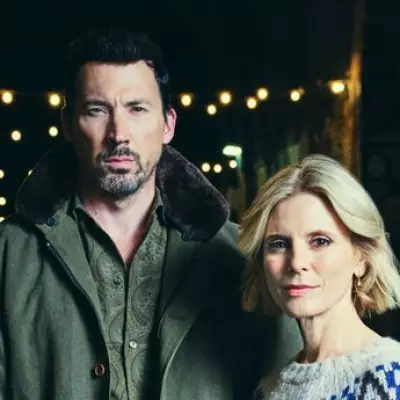

The shift also severs a tactile connection to history and community. Nick Mathews, a journalism professor and former sports editor, notes that the Houston Chronicle would sell out when local teams won championships, as people sought a physical keepsake. His research in Caroline County, Virginia, after the closure of the 99-year-old Caroline Progress, found residents mourning the loss of seeing family milestones in print, with one wistfully noting, "My fingers are too clean now. I feel sad without ink smudges."

Broader Impacts on Democracy and Daily Rituals

Experts argue the change runs deeper than convenience. Anne Kaun, a professor of media studies at Södertörn University in Stockholm, observes that children in homes with physical papers would randomly encounter news, socialising them into a news-reading habit—a process that doesn't occur with personalised mobile feeds.

Sarah Wasserman, a cultural critic at Dartmouth College, suggests this transformation reshapes how we relate to information and each other, affecting attention spans and communication. The physical newspaper, like the payphone or cassette tape, becomes a marker of elapsed time.

The environmental equation is also complex. While printing less paper saves trees, Cecilia Alcoreza of the World Wildlife Fund points out the decline in newsprint is offset by a "huge increase in packaging" from online shopping. Furthermore, old printing plants, like one in Stockholm's Akalla district, are now repurposed as energy-intensive data centres.

The transition milestone was underscored in August when the Atlanta Journal-Constitution announced it would end print editions, making Atlanta the largest U.S. metro area without a daily printed newspaper. As the physical page fades, it takes with it a multifaceted object that once informed, protected, cleaned, and commemorated the rhythms of everyday life.