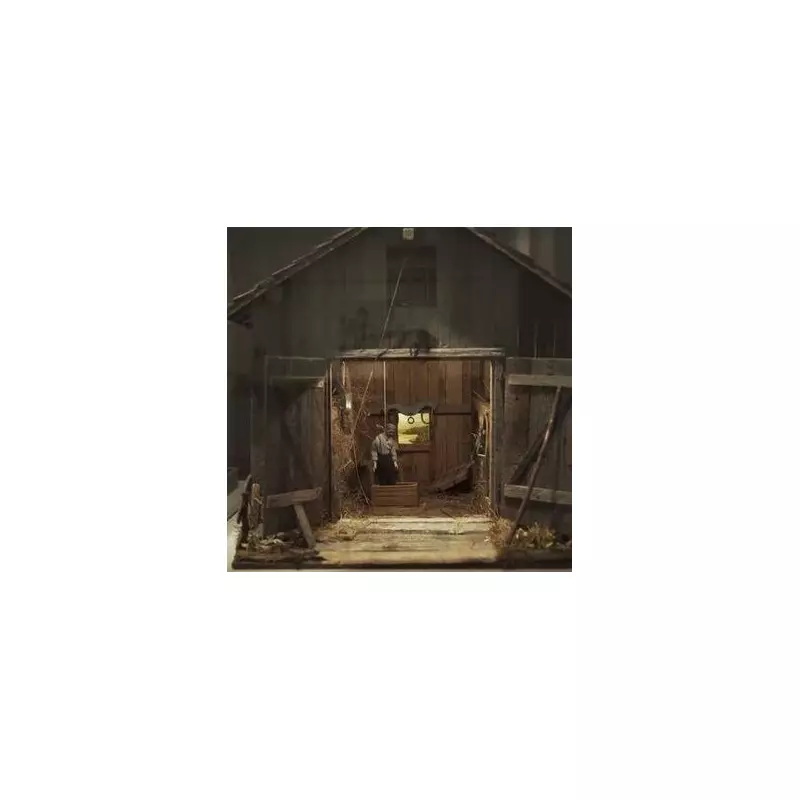

In a remarkable fusion of morbid artistry and scientific rigour, a series of miniature 'houses of horror' containing 18 intricate death scenes were built with one chilling purpose: to train detectives. These dioramas, the brainchild of Frances Glessner Lee, remain a cornerstone of forensic education nearly eight decades later.

The Mother of Forensic Science and Her Macabre Creation

Frances Glessner Lee, often hailed as 'the mother of forensic science', began her groundbreaking work in 1945. Denied a formal university education, her passion for forensic pathology was ignited by her brother's friend, a specialist in death investigation. After inheriting a substantial family fortune at the age of 52, Lee abandoned her socialite life to fund her visionary project.

She established the Harvard Department of Legal Medicine, the first of its kind in the United States. At its heart were the 'Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death' – a collection of 20 meticulously crafted dollhouse dioramas, each based on real autopsies and crime scenes Lee had attended.

Unparalleled Attention to Grisly Detail

The scenes were built to a perfect 1:12 scale and featured an almost unsettling level of detail designed to test the observational skills of investigators. Lee spared no expense, investing $4,500 into each model – a vast sum for the era.

The doll-victims were painted to show bruising or inflated to simulate post-mortem bloating. Floors were spattered with miniature blood, and scenes included clues like a pair of shoes suggesting suicide or tiny bite marks on a victim's neck. Every element, from the pattern on the carpet to the angle of a fallen body, was a potential piece of evidence.

A Legacy That Endures in Modern Training

Lee hosted week-long seminars for detectives, giving them a torch and just 90 minutes to examine a scene and solve the crime. These intense sessions concluded with lavish banquets at the Ritz Carlton.

After her death in 1966 at age 83, the Nutshell Studies were permanently loaned to the Maryland Medical Examiner's Office in Baltimore. They were never updated, preserved exactly as Lee left them. To this day, they are actively used to train homicide investigators enrolled in the Frances Glessner Lee Homicide School, proving that her revolutionary teaching tool remains as valuable now as it was in the mid-20th century.

Lee's work transformed detective training from guesswork into a precise science of observation. Her core principle – to 'convict the guilty, clear the innocent, and find the truth in a nutshell' – continues to guide forensic investigation, one miniature, macabre detail at a time.