On 24th January 1986, nearly 6,000 newspaper workers at Rupert Murdoch's News International empire walked out on strike. This dramatic action was triggered by plans to relocate print operations from the traditional heartland of Fleet Street to a new, technologically advanced plant in Wapping, east London. The move would ignite one of the most acrimonious and protracted industrial conflicts in modern British history.

The Technological Catalyst for Conflict

During the mid-1980s, the majority of British newspapers were still produced using antiquated hot metal typesetting methods. Rupert Murdoch, chairman of News International and publisher of The Sun, News of the World, The Times, and The Sunday Times, was determined to break free from the powerful print unions that dominated Fleet Street. Throughout 1985, he secretly equipped a new facility at Wapping with revolutionary technology that would allow journalists to input copy directly onto computer screens, bypassing traditional printing processes entirely.

Strike Declaration and Immediate Fallout

Following the collapse of negotiations concerning working conditions and the proposed technological changes, a full-scale strike was declared. In a swift and decisive move, Murdoch responded by sacking the striking workers overnight and transferring production of all four titles to the Wapping plant. He employed members of the Electrical, Electronic, Telecommunications and Plumbing Union (EETPU) to operate the new machinery, creating an immediate and profound rift within the trade union movement.

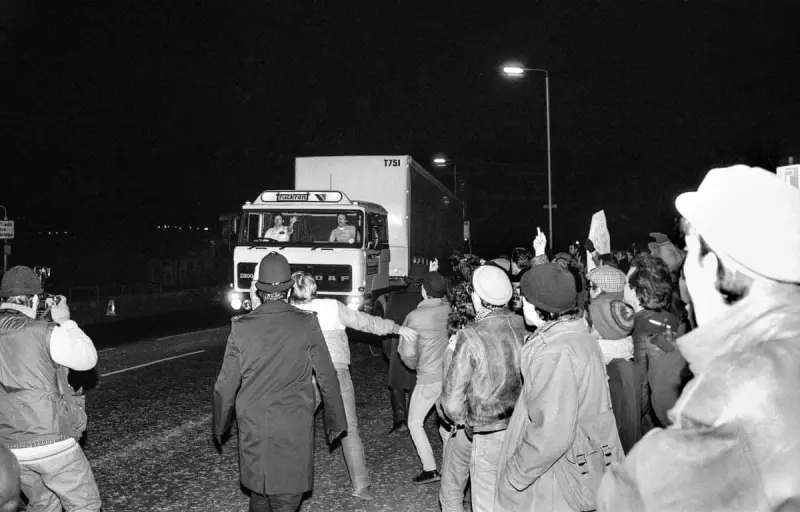

The first newspapers rolled off the presses at Wapping on 25th January 1986. Almost immediately, print unions and their supporters established picket lines at the plant's entrance. What would become known as The Battle of Wapping had commenced in earnest, setting the stage for thirteen months of bitter confrontation, widespread protests, and occasional violence.

Journalists Confronted with an Ultimatum

Senior editorial management met with journalists from The Sun and The Times on the evening of the strike declaration, informing them they were expected to report for work at the new Wapping facility. Management presented journalists with a stark choice: work for the company under the new conditions or remain loyal to their union's instructions. News International offered journalists an additional £2,000 per year plus BUPA membership to operate the new technology, with instant dismissal awaiting those who refused.

Division Within the Ranks

The response from journalists revealed deep divisions. Leaders of the National Union of Journalists (NUJ) argued that management's actions constituted an unwarranted change to employment contracts that need not be obeyed. However, there were clear indications that many journalists would be prepared to cross picket lines and work at Wapping. The Sun journalists, with few exceptions, moved to the new plant and worked normally. The Times journalists were more deeply divided, holding meetings to discuss their position, with a majority eventually voting to go to Wapping under the company's terms.

Meanwhile, distribution staff represented by the Sogat union were instructed not to handle any News International titles, despite acknowledging this action could lead to litigation under the government's secondary action laws.

Production Success Despite Union Opposition

Despite the full-scale strike by the National Graphical Association and Sogat '82 print unions, Murdoch successfully printed both Sunday and daily titles from the Wapping plant with remarkable smoothness. This achievement was made possible through maximum cooperation from the EETPU and substantial support from many NUJ members. Over 1.2 million copies of The Sunday Times and three million copies of The News of the World were produced at Wapping and Glasgow, representing about 60% of the tabloid's usual print run.

The Human Dimension of the Dispute

The conflict had profound personal dimensions for those involved. A core group of approximately thirty journalists, describing themselves as "refuseniks," remained at the traditional Gray's Inn Road offices, determined not to move to Wapping under what they saw as arbitrary notice. One journalist proclaimed they had learned there were "lies, Wapping lies, and Murdoch journalism," while another cited a £60,000 mortgage and young family as reasons for reluctantly moving to the new plant.

At the Wapping plant entrance, a small but determined picket confronted workers arriving for shifts. Pickets shouted "scab" as luxury coaches and private cars passed through ten-foot-tall gates surrounded by razor wire, with some workers reportedly lying on coach floors to avoid being seen.

Broader Political and Industrial Implications

Contemporary editorials recognised that, were it not for the simultaneous Westland affair, Wapping would have dominated every headline and news broadcast. The confrontation was seen as potentially pivotal in the long history of Fleet Street industrial relations, with far-reaching implications for the Labour Party, trade union movement, and approaches to technological change across British industry.

The fundamental question posed by the dispute was how society should manage technological transformation: whether through partnership and agreement within industries, or through resistance to what many workers saw as fundamentally threatening changes to their livelihoods and professions. The Battle of Wapping would continue for over a year, leaving an indelible mark on British media, industrial relations, and the very landscape of newspaper production.