The Green party is facing what critics call a political double standard as it gains momentum under leader Zack Polanski. While the party offers hopeful policies addressing Britain's crises, it's frequently dismissed as naive by establishment voices - particularly from a Labour government that should be its natural ally.

The Pessimism Dominating British Politics

British politics has become dominated by a culture of pessimism, where right-wing voices like Nigel Farage and GB News spread doom about migrants, welfare, and 'wokeness' destroying the country. Meanwhile, the Labour party under Keir Starmer has embraced this negative narrative, arguing that disability cuts are inevitable while wealth taxes remain impossible.

This climate makes it particularly difficult for left-wing parties proposing positive change. As Frances Ryan notes in her Guardian column, politics of hope from the left are routinely dismissed as naive, while centre and right-wing policies are portrayed as the only realistic options.

Labour's Response to Green Party Challenge

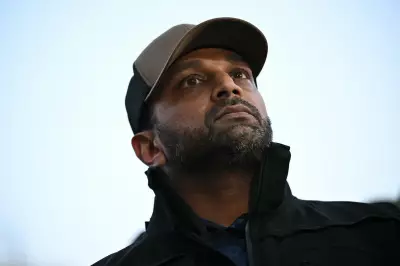

The tension came to a head when Darren Jones, one of Starmer's most influential ministers, publicly criticised the Green party for making what he called 'unfeasible promises.' Speaking to the Guardian, Jones argued that the Greens must explain how they would deliver their policies rather than just making attractive promises.

This remark reveals Labour's strategy as the Greens become a viable electoral threat under Zack Polanski's leadership. The party's recent conference in Bournemouth on 3 October 2025 demonstrated their growing confidence and policy ambition.

The Two-Child Benefit Limit Example

The double standard becomes particularly clear in specific policy debates. The two-child benefit limit, introduced by Conservatives in 2017, has been widely condemned as both a moral and economic failure. The policy has driven child poverty while subjecting women to distressing rape exemption rules.

Yet despite this track record, Chancellor Rachel Reeves only recently hinted at scrapping the policy after pressure from 100 civic organisations. For 18 months, the government claimed it was unaffordable, with Starmer even suspending Labour MPs who opposed it.

This demonstrates how difficult it is for progressive policies to gain traction, even with a Labour government. As Ryan observes, Britain finally has a Labour government, yet we're still debating whether children should go hungry.

Media Bias and Exclusion of Left-Wing Ideas

The problem extends to media coverage, where research by Cardiff University found significant imbalances. Between January and July this year, Reform UK featured in 25% of BBC News at Ten bulletins, while the Liberal Democrats - with 14 times more MPs - appeared in just 17.9%.

Meanwhile, Farage's party was referenced in nearly 20% of ITV News at Ten bulletins, compared to only 6.2% for the Lib Dems. This media landscape means hard-right ideas like mass deportations become mainstream discussions, while left-wing or centre-left thinking is routinely excluded.

Growing Support for Alternative Visions

Despite these challenges, evidence suggests public appetite for positive change is growing. The Green party's increasing support and Zohran Mamdani's recent mayoral victory in New York indicate voters are questioning the narrative that improvement is impossible.

Policies dismissed by establishment figures as radical - such as rent controls and nationalised energy - actually enjoy majority public support. The public sees these measures as mainstream solutions to genuine crises.

The fundamental issue remains: most voters don't need convincing the system is broken. They need inspiration that it can be fixed. The ideas currently dismissed as 'undeliverable' may be exactly what Britain requires to address its mounting problems with private rents, unemployment, and crumbling public services.