Naturalised American citizens are experiencing unprecedented levels of anxiety as President Donald Trump's administration intensifies its immigration enforcement measures, with many now fearing deportation despite their legal status.

A Broken Promise of Belonging

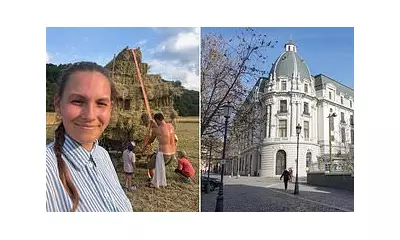

Dauda Sesay, a 44-year-old refugee from Sierra Leone who spent nearly a decade in a refugee camp before settling in Louisiana over 15 years ago, exemplifies this growing dread. After escaping civil war and building a new life in America, Sesay took the oath of allegiance believing it represented an unbreakable bond between himself and his adopted country.

"When I raised my hand and took the oath of allegiance, I did believe that moment the promise that I belonged," said Sesay, who now advocates for refugee integration into American society. For him and countless others, naturalisation represented a steadfast, reciprocal commitment that now feels dangerously fragile.

Travel Restrictions and Domestic Fears

The aggressive push for dramatically increased deportations and efforts to challenge birthright citizenship are creating widespread fear among naturalised citizens. Many now worry about travelling abroad, concerned they might face difficulties returning home after accounts of naturalised citizens being questioned or detained by US border agents.

Some are taking extraordinary precautions, including locking down their phones to protect privacy when crossing borders. Others hesitate to move around within the country itself, following stories like that of a US citizen detained despite his mother producing his birth certificate.

Sesay revealed he no longer travels domestically without his passport, despite possessing a REAL ID with its federally mandated, stringent identity requirements. This reflects the depth of uncertainty gripping naturalised Americans.

Expanding Enforcement and Legal Challenges

Immigration enforcement roundups have intensified, often conducted by masked, unidentifiable federal agents in cities including Chicago and New York City. These operations have occasionally swept up American citizens in their dragnets, leading to at least one federal lawsuit from a US citizen who claims immigration agents detained him twice.

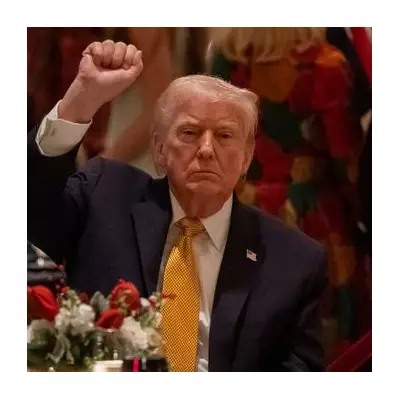

Adding to concerns, the Justice Department issued a memo this summer announcing it would ramp up efforts to denaturalise immigrants who have committed crimes or are deemed national security risks. The situation became particularly stark when President Trump directly threatened the citizenship of Zohran Mamdani, the 34-year-old democratic socialist mayor-elect of New York City, who naturalised as a young adult.

The atmosphere has grown so tense that many naturalised citizens fear speaking publicly, with numerous community organisations failing to find individuals willing to comment on record beyond Sesay.

Historical Context of American Citizenship

Stephen Kantrowitz, professor of history at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, notes that what citizenship has meant—and who qualifies—has expanded and contracted throughout American history. "When the Constitution is written, nobody knows what citizenship means," Kantrowitz explained. "It's a term of art that comes out of the French revolutionary tradition."

The first naturalisation law passed in 1790 restricted citizenship to any "free white person" of good character. Those of African descent were added as a specific category after the Civil War, when the 14th Amendment established birthright citizenship.

Later restrictions included the Immigration Act of 1924, which effectively barred people from Asia because they were ineligible for naturalisation. Racial restrictions weren't removed until 1952, with the 1965 Immigration and Naturalisation Act creating the current system that portions out visas equally among nations.

American history contains precedents for citizenship revocation, including after the 1923 Supreme Court ruling in US vs. Bhagat Singh Thind, which declared Indians ineligible for naturalisation and led to several dozen denaturalisations. During World War II, Japanese Americans saw their citizenship effectively ignored when forced into internment camps.

"Political power will sometimes simply decide that a group of people, or a person or a family isn't entitled to citizenship," Kantrowitz observed.

Contemporary Echoes of Historical Exclusion

In New Mexico, state Senator Cindy Nava recognises the current fear, having grown up undocumented before obtaining DACA protection and eventually gaining citizenship through marriage. She expresses surprise at seeing such apprehension among naturalised citizens.

"I had never seen those folks be afraid... now the folks that I know that were not afraid before, now they are uncertain of what their status holds in terms of a safety net for them," Nava said.

For Sesay and many others who chose America as their home, the current climate feels like a profound betrayal. "The United States of America—that's what I took that oath of allegiance, that's what I make commitment to," Sesay said. "Now, inside my home country, and I'm seeing a shift... Honestly, that is not the America I believe in when I put my hand over my heart."