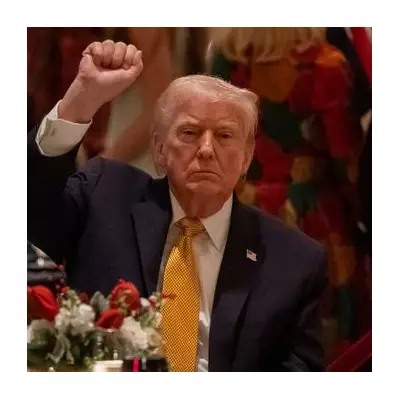

In a year where racist and nativist rhetoric has moved to the political forefront, the crude demand for people to 'go home' has taken on a renewed and ugly resonance. This call, recently directed at Deputy Prime Minister and Justice Secretary David Lammy by a Nigel Farage associate, exposes a profound confusion about identity and belonging in modern Britain.

Lammy, the MP for Tottenham for 25 years and a senior government figure, was told he should 'go home to the Caribbean'. The comment, made without notable condemnation from the Reform UK party, reflects a broader climate where 'othering' has become a mainstream political sport.

A Toxic Political Climate in 2025

The past year witnessed a significant escalation in public bigotry. High-profile incidents included the violent besieging of asylum seeker hotels, condoned by some right-wing politicians and media. The British and St George's flag was widely deployed not as a symbol of unity, but as one of intimidation by hard-right activists.

Furthermore, allegations surfaced that Nigel Farage, a figure with national leadership ambitions, had been a racist school bully and refused to properly atone for the hurt caused.

Beyond the headlines, countless lower-profile aggressions occurred. A black friend was called a 'black bitch' by a motorist in Middle England, seemingly to impress a younger passenger. A student and his father were warned out of a West Country pub for being 'Pakis'. A black health worker driving through union flag-draped villages felt, for the first time, the need to watch his back.

According to a new study by the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR), the number of people absorbing and mirroring hard-right narratives is rising. This prompts a urgent national question: is a divided, resentful, and culturally hostile country what the majority wants?

The Precarious Nature of Belonging for Minorities

Against this backdrop, the concept of 'home' for minorities feels increasingly unstable. As the son of Windrush-era parents, the author's own footing has always been conditional. His parents arrived in the 1950s believing their status was secure, only to have it undermined by the 1971 Immigration Act, forcing them to pay to re-secure their rights.

This insecurity persists. Under the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002, the Home Secretary can strip a British citizen of citizenship without notification if it is deemed for the 'public good'. Research by the Runnymede Trust this year suggested 9 million people, mainly those with dual nationalities, are vulnerable, with minority citizens 12 times more at risk than white citizens. The message is clear: you belong until, one day, you might not.

DNA and the Illusion of a Single Homeland

The command to 'go home' is revealed as a nonsense when examined through the lens of personal history and genetics. Where is 'home' if not where you were born, raised, work, and pay taxes?

A personal DNA test undertaken by the author answered the question with stunning complexity. The results showed ancestral links to at least 15 different places.

On his mother's side, the test revealed traces from Benin and Togo, significant parts from Côte d'Ivoire and Ghana, along with Nigeria, Mali, north-east Scotland, and even Iceland. From his father, there was more Benin, Togo, and Côte d'Ivoire, but a predominant link to Nigeria, alongside Devon and Somerset, Cameroon, Mali, Senegal, Panama, Costa Rica, and the Netherlands.

This genetic tapestry is energising and fundamentally challenges the populist notion of people as identity parcels with a single return address. It underscores that through history, politics, cruelty, and happenstance, many British people are 'creatures from almost everywhere'.

The truth of Britain is one of deep, intertwined roots. A conversation about home and belonging that starts from this point of complex, shared heritage would be far more positive and accurate than one driven by exclusion and prejudice. It is a conversation the country desperately needs to have.