The national director of the progressive Working Families Party has declared "the time has come" for a viable third force in American politics, following a significant year of electoral victories and growing voter disillusionment with the two major parties.

A Movement Meeting Its Moment

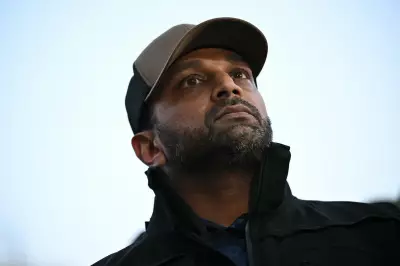

Maurice Mitchell, the party's national director, stated that after 26 years of groundwork, the party's argument for a new political home has finally aligned with the public mood. "The argument has met the moment," Mitchell asserted, pointing to a widespread hunger among voters for alternatives to the Democratic and Republican brands, which he described as consistently "underwater."

The party, founded in 1998, has expanded rapidly, with much of its growth occurring in the past five years. It is now officially active in 18 states and can appear directly on the ballot in three: New York, Connecticut, and Oregon. Its membership exceeds 600,000, supported by over 100 staff members.

Strategic Wins and National Inroads

The past year has seen the party notch up several crucial successes. It played a pivotal role in electing Zohran Mamdani as Mayor of New York City in an upset victory. Notably, in that race, more New Yorkers voted for mayor on the Working Families ballot line than on the Republican line.

Beyond its deep-blue urban strongholds, the party has made inroads in cities like Dayton, Ohio, and Buffalo, New York. Its strategy often involves endorsing insurgent candidates running in Democratic primaries who champion working-class politics, affordability, workers' rights, and democratic reform.

"We cook what we have in the kitchen," Mitchell said, explaining the pragmatic approach of sometimes endorsing the same candidates as the Democrats while building independent power.

Dismantling Barriers and Building a Wave

The party is actively working to dismantle structural barriers that hinder third-party success in the US. A major victory came in New Jersey in 2024, where it helped abolish the controversial "line" system that gave party bosses undue influence over ballot design. "It's been a watershed moment in New Jersey politics," Mitchell noted, with multiple party-aligned candidates subsequently elected.

In Jersey City, a Working Families-endorsed mayor, James Solomon, won office, and the party gained a governing majority on the city council. Katie Brennan, a candidate elected without Democratic party backing, said voters are tired of a broken system and are increasingly familiar with the Working Families alternative.

Looking ahead, the party is betting on the 2026 midterms as a potential wave year for the left. It plans aggressive recruitment for state legislature races, aiming not just to flip chambers from red to blue, but to "Working Families orange." It has already announced primary challengers in three congressional districts and launched a candidate recruitment drive focused on opposing data centres.

"If there's going to be a wave election, the ink hasn't been dried on the character of that wave, who led that wave, and how that wave was won," Mitchell said, signalling the party's intent to define that coming political shift.

The party's rise has not been without attempts at sabotage, with Republican operatives reportedly running spoiler candidates under the Working Families banner to split the Democratic vote—a tactic Mitchell called "desperate" but a backhanded recognition of the party's growing influence.