A Damascus suburb that became one of the Syrian regime's most notorious killing fields continues to haunt its residents years after the atrocities occurred. Tadamon, a working-class district in south-east Damascus, witnessed systematic mass executions and burning of civilians during the height of the conflict, with many perpetrators still living freely in the neighbourhood.

The Smell of Death

Abu Mohammed, a retired engineer who asked to be identified only by his nickname, recalls the distinctive odour that permeated his neighbourhood beginning in winter 2012. "It usually came at dawn, as the mosques sounded the first call to prayer," he remembered. The smell was difficult to define but unmistakable - a combination of burning hair and meat left too long in a pan.

Living in a modest flat just off Daboul Street with his wife and five children, Abu Mohammed watched as his once-vibrant neighbourhood transformed. The streets grew deserted as the Assad regime established checkpoints to quell protests following the 2011 uprising. White minibuses became a regular sight, their appearance often followed by gunfire and that same disturbing smell overnight.

His daughter, then in her early teens, confirms the memory. "It smelt like burning hair," she said. "Or like a piece of meat that has been left in a pan until it melts."

The Video Evidence

In April 2022, the Guardian published chilling video footage that finally revealed the source of the smell. Dated April 2013 and geolocated to Tadamon, the video showed two soldiers in military fatigues executing civilians beside a white minibus. The footage depicted a systematic process: blindfolded civilians were pulled from the vehicle, dragged toward a large pit filled with bodies and car tyres, then executed and set ablaze.

The video was part of a collection obtained by genocide scholars Annsar Shahhoud and Uğur Ümit Üngör from a source inside Syria. Their analysis concluded the footage documented the killing of 288 civilians by Assad's forces, including seven women and twelve children.

Through meticulous investigation, Shahhoud identified the main shooter as Amjad Youssef, an officer in Branch 227 of the Assad regime's military intelligence. Using a fake Facebook account posing as a regime loyalist, she gained his trust and eventually lured him into confessing. When confronted with the video evidence, Youssef responded: "I am proud of my deeds."

Living Among Perpetrators

Despite the damning evidence, residents say Youssef remained in the neighbourhood after the video's publication, driving up and down the streets on his motorbike as if nothing had happened. "No one would say anything," Abu Mohammed noted, reflecting the climate of fear that persisted while Assad remained in power.

Now, with the dictator gone, the people of Tadamon are breaking their silence. Multiple visits to the neighbourhood between March and August this year revealed that the atrocities were far more extensive than initially reported and involved numerous perpetrators beyond Youssef.

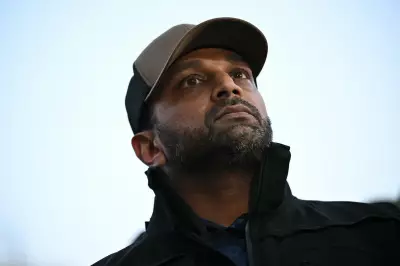

Abu Mohammed, described as a short elderly man with a soft smile, became a guide to the neighbourhood's dark history. "I stayed here throughout the war," he told journalists. "If you want to know what really happened here, follow me."

The Scale of Destruction

The video footage captured only a fraction of the slaughter, according to residents. Abu Mohammed estimates the killing of civilians in Tadamon wasn't a single event but occurred regularly over years. He witnessed the minibuses driving through the neighbourhood two or three times weekly, with the smell of burning bodies returning repeatedly from late 2012 until at least 2015.

The actual death toll may number in the thousands rather than hundreds, though precise figures remain difficult to establish. The neighbourhood itself bears physical scars of the violence, divided by Daboul Street into contrasting zones. To the west, narrow alleyways buzz with life where children play and street vendors sell fresh fruit. To the east lies a wasteland spanning over fifty football fields, filled with rubble and the ruins of bombed apartment blocks.

"This is where the smell came from," Abu Mohammed explained, stepping into the ruined area. Local children, disturbingly familiar with the neighbourhood's history, spontaneously re-enacted the executions for visiting journalists. "This is how he killed him!" one ten-year-old boy shouted while waving an imaginary rifle. "I saw it myself on YouTube."

Mass Graves and Torture Sites

Throughout the wasteland, evidence of mass graves continues to surface. Abu Mohammed showed journalists a shallow crater inside one destroyed building containing human bones, including a skull, spinal fragments, and smaller bones that may have belonged to children. Stray dogs regularly uncover human remains as they dig through the rubble.

Nearby, a building with pink walls covered in regime graffiti contained a metal bar hanging from the ceiling - a former torture site where victims were suspended by their wrists. Many people killed in such locations were simply dumped in the wasteland or stacked into empty buildings that were subsequently bombed to conceal evidence.

The Othman bin Affan mosque, standing on the border between intact neighbourhoods and the rubble, played a central role in the regime's killing machine. Abu Mohammed recalls passing the mosque in 2014 with his nine-year-old daughter and seeing piles of corpses outside. The mosque's caretaker, Naji, showed visitors the basement used as a torture chamber, where bones still littered the floor and a noose once hung from the ceiling.

Forced Participation

Perhaps the most disturbing revelations come from those forced to participate in the atrocities. Abu Mohammed's son, identified only as "Ahmed" to protect his identity, revealed he was regularly taken by paramilitaries from the National Defence Force (NDF) while on his way to high school.

Initially forced to perform manual labour like filling sandbags or stripping copper from electrical cables, Ahmed was twice compelled to participate in burning bodies. He described being taken to the Othman bin Affan mosque where at least twenty bodies of men and women bearing signs of severe beatings lay in the street.

"Our job was to take the bodies to the other side of the main street, where there were a lot of demolished buildings and rubble," Ahmed recalled softly. "There we would stack them inside an empty building, close it off, and set the place on fire." He would return home smelling of burning bodies, too terrified to tell anyone what he had been forced to do.

The Road to Justice

Following Assad's fall on 8 December 2024, surprisingly little violence occurred in Tadamon despite expectations of revenge killings. Former rebel commander Malek Moustafa, who had fantasised about revenge during six years of displacement, found himself embracing a former NDF member when he returned home.

Moustafa and other activists have relaunched the Tadamon Coordination Committee, focusing on rebuilding rather than retaliation. They distribute bread, manage community news sources, and work with local security forces to install surveillance cameras throughout the neighbourhood.

However, justice remains elusive. Only a handful of perpetrators have been arrested, and public anger focuses particularly on Fadi "Saqr" Ahmad, the local Alawite who helped establish and lead the NDF in Tadamon. Instead of facing trial, Saqr has reportedly begun working with the new government, appearing in the neighbourhood under security escort and assisting with disarmament negotiations.

This collaboration has sparked protests, with residents hanging an effigy of Saqr from a makeshift gallows. The government defends its approach, with civil peace committee member Hassan Soufan explaining that "in this phase of civil peace, we are sometimes forced to make decisions to avoid more violent explosions."

Saqr himself denies responsibility for the Tadamon massacre, claiming he was appointed to lead the NDF only after the April 2013 killings shown in the video. "If the ministry of interior had any evidence against me, I wouldn't be working with them today," he stated.

Meanwhile, simmering tensions threaten to erupt into violence as residents struggle with the ongoing presence of alleged perpetrators in their community. As Abu Mohammed noted, "People have vengeance in their hearts." The challenge for Syria's future may lie in balancing the urgent need for justice with the fragile peace that currently prevails.