Groundbreaking research has uncovered a startling chain of events linking massive volcanic eruptions in the 14th century to the catastrophic arrival of the Black Death in Europe. A new study paints the most detailed picture yet of the 'perfect storm' that led to tens of millions of deaths and reshaped the continent's society, economy, and politics.

The Climate Domino Effect

Scientists from the University of Cambridge and Germany's Leibniz Institute for the History and Culture of Eastern Europe (GWZO) have identified a series of volcanic eruptions around 1345 as the critical first domino. By analysing climate data preserved in ancient tree rings and historical documents, they found these eruptions spewed vast amounts of ash and gases into the atmosphere, creating a haze that caused annual temperatures to plummet for several consecutive years.

This volcanic winter led directly to widespread crop failures and famine across the Mediterranean region. 'We looked into the period before the Black Death with regard to food security systems and recurring famines,' explained historian Dr Martin Bauch from GWZO. 'This was important to put the situation after 1345 in context.'

Trade, Grain, and a Deadly Stowaway

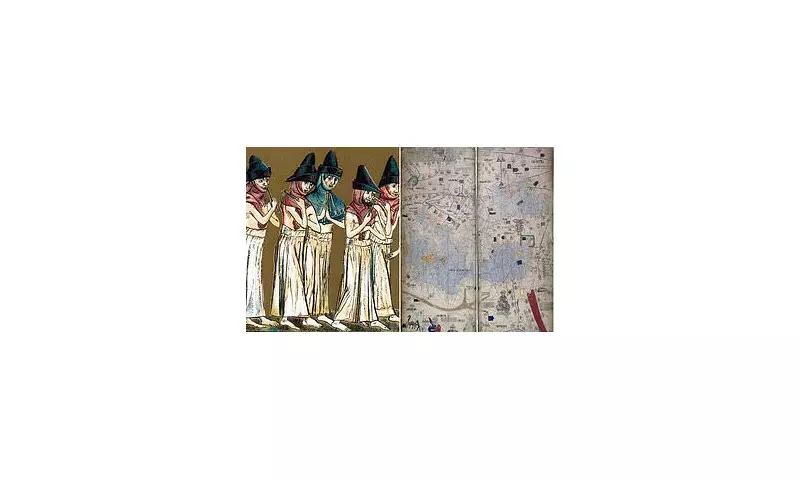

Facing potential starvation and social unrest, powerful Italian maritime republics like Venice, Genoa, and Pisa activated their long-distance trade networks. They turned to grain producers around the Black Sea, specifically trading with the Mongols of the Golden Horde near the Sea of Azov by 1347.

'For more than a century, these powerful Italian city states had established long-distance trade routes across the Mediterranean and the Black Sea, allowing them to activate a highly efficient system to prevent starvation,' said Dr Bauch. 'But ultimately, these would inadvertently lead to a far bigger catastrophe.'

The grain ships that saved populations from famine carried an unseen and deadly passenger. Researchers believe the vessels also harboured fleas infected with the bacterium Yersinia pestis, which causes bubonic plague. The bacterium is thought to have originated in wild rodents in central Asia. These plague-infected fleas became a deadly vector, enabling the disease to jump to humans upon the ships' arrival in Mediterranean ports.

Evidence Locked in Tree Rings and History

The research team, led by Cambridge geography Professor Ulf Büntgen, used innovative methods to pinpoint the volcanic trigger. They studied tree rings from the Spanish Pyrenees, where consecutive 'Blue Rings' indicated unusually cold, wet summers in 1345, 1346, and 1347.

'This is something I've wanted to understand for a long time,' said Professor Büntgen. 'What were the drivers of the onset and transmission of the Black Death? Why did it happen at this exact time and place in European history?'

Historical records from the period corroborate the climatic chaos, noting unusual cloudiness and dark lunar eclipses—classic signs of atmospheric volcanic dust. Between 1347 and 1353, the Black Death ravaged Europe, killing millions with a mortality rate approaching 60% in some areas.

The study, published in Communications Earth and Environment, is the first to draw a direct line using high-quality natural and historical data between climate, agriculture, trade, and the plague's origins. It also notes that cities like Milan and Rome, which did not need to import grain, were largely spared, strengthening the climate-trade connection.

A Historical Lesson for a Globalised World

The researchers describe the convergence of volcanic activity, climate shift, crop failure, and globalised trade as an early example of the complex risks in an interconnected world. 'Although the coincidence of factors that contributed to the Black Death seems rare, the probability of zoonotic diseases emerging under climate change and translating into pandemics is likely to increase in a globalised world,' warned Professor Büntgen. 'This is especially relevant given our recent experiences with Covid-19.'

They argue that modern risk assessments must learn from these historical interactions between climate, disease, and society. The legacy of the plague is still visible today; in Cambridge, for instance, Corpus Christi College was founded by townspeople in the aftermath of the local devastation, a story repeated across the continent.