Millions of Britons using revolutionary weight-loss injections may need to remain on them indefinitely to keep the pounds off, a major scientific review has concluded.

The 'Rapid Rebound' Effect

In the first analysis of its kind, Oxford University researchers examined 37 studies involving more than 9,300 people. They discovered that when patients stop taking medications like Wegovy and Mounjaro, the lost weight returns swiftly, regardless of how much was initially shed.

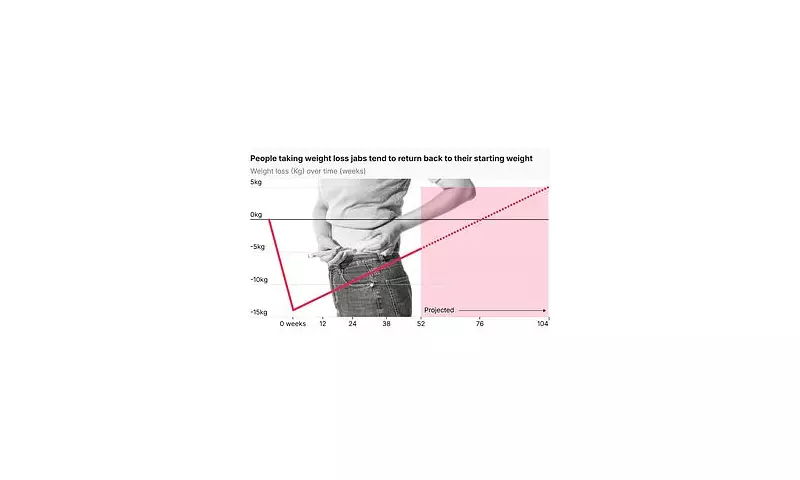

On average, users regained around one pound (0.4kg) per month after quitting. The data projects that many would have regained most or all of their lost weight within 17 to 20 months of ending treatment.

Professor Susan Jebb, a study co-author and government adviser on obesity, framed the issue clearly. 'Obesity is a chronic relapsing condition,' she stated. 'I think one would expect that these treatments need to be continued for life, just in the same way as blood pressure medication.'

Heart Health Benefits Also Reversed

The research, published in The British Medical Journal, delivered a further crucial finding. Stopping the drugs does not merely reverse weight loss; it also leads to a reversal of key cardiometabolic benefits.

Improvements in blood sugar, blood pressure, and cholesterol levels returned to pre-treatment baselines in under 18 months. This is a significant concern, as improved heart health is a major selling point for these medications.

The weight return was strikingly faster than for those who lost weight through traditional means. Patients who stopped the jabs regained weight around four times quicker than individuals who had slimmed down using diet and exercise programmes alone.

Policy and Cost Implications

These findings pose serious questions for current NHS policy, which currently offers Wegovy for a maximum period of two years. The study suggests this limited timeframe may be fundamentally at odds with the long-term nature of obesity.

With an estimated 2.5 million people in the UK now using these GLP-1 drugs, the long-term financial burden is a pressing issue. Most patients access the injections privately, often paying up to £300 per month.

Professor Jebb highlighted the adherence challenge, noting that around half of people discontinue these medications within a year. 'We should see this as a chronic treatment for a chronic condition,' she added.

Dr Adam Collins, an associate professor of nutrition not involved in the study, explained the biological mechanism. 'As soon as the drug is stopped, appetite is no longer kept in check,' he said. 'If people haven't built sustainable habits alongside treatment, going cold turkey can be extremely difficult.'

The research underscores the scale of Britain's obesity crisis. Two in three adults are now overweight or obese, and the condition is linked to at least 13 types of cancer and fuels rising type 2 diabetes rates.

While the drugs represent a breakthrough, experts like Professor John Wilding from the University of Liverpool stress they are not a quick fix. 'These drugs should be considered long-term treatments,' he concluded.