In a groundbreaking scientific endeavour, researchers are preparing to drill one kilometre deep into Antarctica's ominously nicknamed 'Doomsday Glacier' to investigate the underwater processes that could have catastrophic consequences for global sea levels. This marks the first time scientists have ever drilled into the Thwaites Glacier, a colossal ice mass covering an area nearly the size of the United Kingdom.

Unprecedented Access to a Climate Threat

The Thwaites Glacier, with ice up to 2,000 metres thick, represents one of the planet's most significant climate vulnerabilities. Researchers warn that its complete collapse could cause global sea levels to rise by approximately 65 centimetres, threatening coastal communities worldwide. The upcoming mission will focus on the glacier's main trunk, a highly crevassed and previously unexplored region considered its most unstable section.

The Challenge of Underwater Tsunamis

Central to the investigation are so-called "underwater tsunamis" – massive underwater waves with amplitudes ranging from 10 to hundreds of metres. These phenomena mix deep, warm ocean water with surface layers, accelerating ice melt from below. Dr Alex Brearley, an oceanographer at the British Antarctic Survey, explained that understanding these processes is essential for improving predictions about sea ice melt and future sea level rise.

"These big underwater waves, with amplitudes of 10s to possibly hundreds of meters, what that can do is mix deep water with water closer to the surface," Dr Brearley told Sky News Australia. "We have to understand that in order to make those better predictions about sea ice melt."

International Collaboration in Extreme Conditions

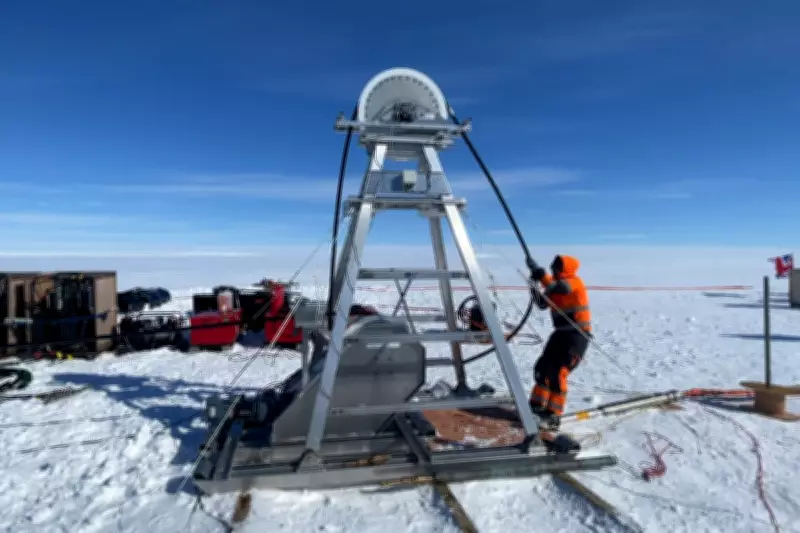

Over the next two weeks, a joint team from the British Antarctic Survey and the Korea Polar Research Institute will deploy a hot water drill to bore through the ice. The technology involves heating water to around 90 degrees Celsius and pumping it at high pressure through a hose, melting ice at approximately one metre per minute to create a 30-centimetre diameter hole.

Dr Peter Davis, a physical oceanographer at BAS, described the project as an "extremely challenging mission" on "one of the most important and unstable glaciers on the planet." He emphasised the significance of real-time observation: "For the first time, scientists will be watching, in near real time, what warm ocean water is doing to the ice 1,000 metres below the surface. This has only recently become possible – and it's critical for understanding how fast sea levels could rise."

Technological Expertise and Historical Context

The drilling operation targets the precise point where the glacier lifts off the seabed to become a floating ice shelf – the area where Thwaites is most vulnerable to warm ocean water intrusion. Keith Makinson, a drilling engineer with BAS, highlighted the organisation's 75 years of hot water drilling experience, describing the team as "world-leaders in this technology."

"Over the past four decades it's been amazing to see this technology develop, and now it's helping to answer crucial questions about how we're all going to be affected by climate change and rising sea levels," Makinson said.

Dr Won Sang Lee, principal research scientist at KOPRI, characterised the mission as "polar science in the extreme," noting the team undertook an "epic journey with no guarantee we'd even be able to make it onto the ice." He credited the successful deployment preparations to the "skills and expertise of everyone involved from KOPRI and BAS."

Broader Implications for Climate Science

Previous research on Thwaites Glacier has concentrated on more stable areas, making this venture into its treacherous main trunk particularly significant. The data collected from instruments lowered through the borehole will provide unprecedented insights into the glacier's behaviour and vulnerability.

This mission represents a crucial step in understanding one of climate change's most pressing threats. As scientists gather real-time data from deep within the glacier, they move closer to answering fundamental questions about the pace of sea level rise and the future stability of Antarctica's ice sheets.