In a move that sounds more like science fiction than science policy, private companies are now actively developing and deploying technologies designed to block out the sun's rays to cool the planet. This radical approach, known as solar geoengineering or solar radiation modification, is gaining unprecedented momentum and investment, even as it divides the scientific community and raises profound ethical and regulatory questions.

The Start-Up Rush to Modify the Atmosphere

The race entered a new phase in October 2025 when a secretive start-up called Stardust Solutions announced it had raised $60 million – the largest investment ever for a company in this field. Founded in 2023 by Israeli nuclear physicists Yanai Yedvab and Amyad Spector, along with former Israeli Atomic Energy Commission chief scientist Eli Waxman, the firm aims to bounce sunlight back into space using reflective particles released into the stratosphere.

Stardust is tight-lipped about its specific technology but claims its patent-pending particle will be non-sulfate, avoiding the ozone depletion and acid rain linked to materials like sulphur dioxide. "Given the escalating crisis it would be irresponsible not to do the work now," Yedvab told The Independent, arguing research must be completed now so governments have options in future. The company insists any deployment would be solely under government control.

Live Experiments and Regulatory Gaps

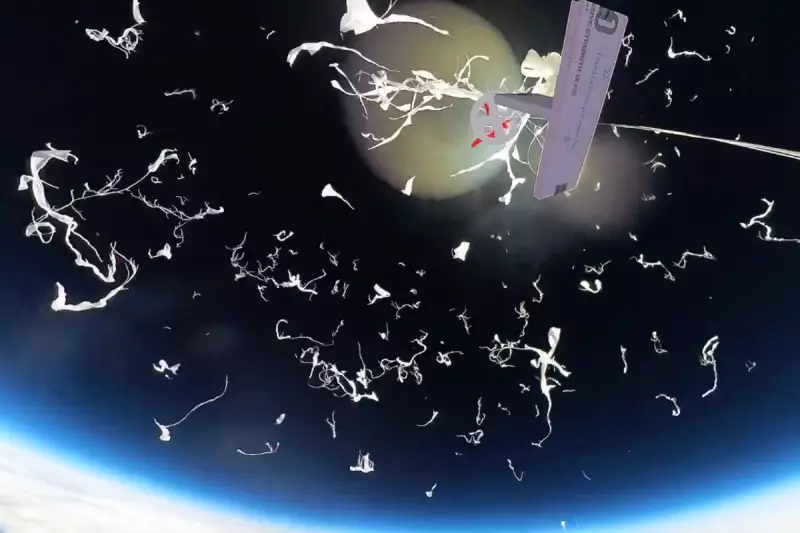

While Stardust plans future outdoor tests, another company is already acting. Make Sunsets, founded in 2022, has launched over 213 weather balloons filled with sulphur dioxide particles from a Winnebago RV in California. The start-up, founded by former Y Combinator director Luke Iseman and ex-Indiegogo executive Andrew Song, sells "cooling credits" claiming each gram of sulphur offsets a ton of CO2 for a year.

This rogue activity highlights a major void: there are no binding international rules governing solar geoengineering. While the UK's Advanced Research and Invention Agency (ARIA) launched a £75 million government-backed research programme in April 2025, including experiments to thicken Arctic ice, regulation elsewhere is patchy. Mexico banned the practice after Make Sunsets launched balloons there without permission, and the US Environmental Protection Agency has demanded information from the company, with Administrator Lee Zeldin criticising "climate extremism." At least 19 US states have seen bills to ban various forms of geoengineering.

A Controversial 'Plan B' for a Warming World

Proponents view solar geoengineering as a potential emergency brake, a way to buy crucial time by lowering global temperatures rapidly while the world struggles to cut emissions. They point to the temporary cooling effect of volcanic eruptions, like Mount Pinatubo in 1991, which lowered global temperatures by about 0.5°C.

However, a formidable coalition of scientists and advocates condemns the approach. Critics argue it is a dangerous distraction from decarbonisation, fraught with risks like disrupting regional weather patterns, causing "termination shock" if stopped abruptly, and being governed by profit motives rather than public good. David Keith of the University of Chicago called Stardust's claims of a novel, safe particle "total, unadulterated bulls***." The UK Royal Society has warned of potential adverse impacts, including more ferocious hurricanes and worsened droughts.

As the climate crisis intensifies—exemplified by the likely irreversible decline of ocean corals—the debate over this once-fringe idea is moving from academic journals to boardrooms and government departments. The world must now grapple not just with how to stop emitting greenhouse gases, but with whether deliberately dimming the sun is a brave new solution or a catastrophic mistake.